History & Faith (Part 2)

by J. Gresham Machen (1915)

In order to better understand the full context of this section of Machen’s essay, here’s the concluding paragraph from Part 1 (click here to read this part in its entirety):

Separate the natural and the supernatural in the Gospel account of Jesus—that has been the task of modern liberalism. How shall the work be done? We must admit at least that the myth-making process began very early; it has affected even the very earliest literary sources that we know. But let us not be discouraged. Whenever the mythical elaboration began, it may now be reversed. Let us simply go through the Gospels and separate the wheat from the tares. Let us separate the natural from the supernatural, the human from the divine, the believable from the unbelievable. When we have thus picked out the workable elements, let us combine them into some sort of picture of the historical Jesus. Such is the method. The result is what is called “the Liberal Jesus.” It has been a splendid effort. I know scarcely any more brilliant chapter in the history of the human spirit than this “quest of the historical Jesus.” The modern world has put its very life and soul into this task. It has been a splendid effort. But it has also been — a failure.

In the first place, there is the initial difficulty of separating the natural from the supernatural in the Gospel narrative. The two are inextricably intertwined. Some of the incidents, you say, are evidently historical; they are so full of local color; they could never have been invented. Yes, but unfortunately the miraculous incidents possess exactly the same qualities. You help yourself, then, by admissions. Jesus, you say, was a faith-healer of remarkable power; many of the cures related in the Gospels are real, though they are not really miraculous. But that does not carry you far. Faith-healing is often a totally inadequate explanation of the cures. And those supposed faith-cures are not a bit more vividly, more concretely, more inimitably related than the most uncompromising of the miracles. The attempt to separate divine and human in the Gospels leads naturally to a radical skepticism. The wheat is rooted up with the tares. If the supernatural is untrue, then the whole must go, for the supernatural is inseparable from the rest. This tendency is not merely logical; it is not merely what might naturally be; it is actual. Liberal scholars are rejecting more and more of the Gospels; others are denying that there is any certainly historical element at all. Such skepticism is absurd. Of it you need have no fear; it will always be corrected by common sense. The Gospel narrative is too inimitably concrete, too absolutely incapable of invention. If elimination of the supernatural leads logically to elimination of the whole, that is simply a refutation of the whole critical process. The supernatural Jesus is the only Jesus that we know.

In the second place, suppose this first task has been accomplished. It is really impossible, but suppose it has been done. You have reconstructed the historical Jesus—a teacher of righteousness, an inspired prophet, a pure worshipper of God. You clothe him with all the art of modern research; you throw upon him the warm, deceptive, calcium-light of modern sentimentality. But all to no purpose! The liberal Jesus remains an impossible figure of the stage. There is a contradiction at the very center of his being. That contradiction arises from his Messianic consciousness. This simple prophet of yours, this humble child of God, thought that he was a heavenly being who was to come on the clouds of heaven and be the instrument in judging the earth. There is a tremendous contradiction here. A few extremists rid themselves easily of the difficulty; they simply deny that Jesus ever thought he was the Messiah. An heroic measure, which is generally rejected! The Messianic consciousness is rooted far too deep in the sources ever to be removed by a critical process. That Jesus thought he was the Messiah is nearly as certain as that he lived at all. There is a tremendous problem there. It would be no problem if Jesus were an ordinary fanatic or unbalanced visionary; he might then have deceived himself as well as others. But as a matter of fact he was no ordinary fanatic, no megalomaniac. On the contrary, his calmness and unselfishness and strength have produced an indelible impression. It was such an one who thought that He was the Son of Man to come on the clouds of heaven. A contradiction! Do not think I am exaggerating. The difficulty is felt by all. After all has been done, after the miraculous has carefully been eliminated, there is still, as a recent liberal writer has said, something puzzling, something almost uncanny, about Jesus. He refuses to be forced into the mold of a harmless teacher. A few men draw the logical conclusion. Jesus, they say, was insane. That is consistent. But it is absurd.

Suppose, however, that all these objections have been overcome. Suppose the critical sifting of the Gospel tradition has been accomplished, suppose the resulting picture of Jesus is comprehensible—even then the work is only half done. How did this human Jesus come to be regarded as a superhuman Jesus by his intimate friends, and how, upon the foundation of this strange belief was there reared the edifice of the Christian Church?

In the early part of the first century, in one of the petty principalities subject to Rome, there lived an interesting man. Until the age of thirty years he led an obscure life in a Galilean family, then began a course of religious and ethical teaching accompanied by a remarkable ministry of healing. At first his preaching was crowned with a measure of success, but soon the crowds deserted him, and after three or four years, he fell victim in Jerusalem to the jealousy of his countrymen and the cowardice of the Roman governor. His few faithful disciples were utterly disheartened; his shameful death was the end of all their high ambitions. After a few days, however, an astonishing thing happened. It is the most astonishing thing in all history. Those same disheartened men suddenly displayed a surprising activity. They began preaching, with remarkable success, in Jerusalem, the very scene of their disgrace. In a few years, the religion that they preached burst the bands of Judaism, and planted itself in the great centers of the Graeco-Roman world. At first despised, then persecuted, it overcame all obstacles; in less than three hundred years it became the dominant religion of the Empire; and it has exerted an incalculable influence upon the modern world.

Jesus himself, the founder, had not succeeded in winning any considerable number of permanent adherents; during his lifetime, the genuine disciples were comparatively few. It is after his death that the origin of Christianity as an influential movement is to be placed. Now it seems exceedingly unnatural that Jesus' disciples could thus accomplish what he had failed to accomplish. They were evidently far inferior to him in spiritual discernment and in courage; they had not displayed the slightest trace of originality; they had been abjectly dependent upon the Master; they had not even succeeded in understanding him. Furthermore, what little understanding, what little courage they may have had was dissipated by his death. “Smite the shepherd, and the sheep shall be scattered.” How could such men succeed where their Master had failed? How could they institute the mightiest religious movement in the history of the world?

Of course, you can amuse yourself by suggesting impossible hypotheses. You might suggest, for instance, that after the death of Jesus his disciples sat quietly down and reflected on his teaching. “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” “Love your enemies.” These are pretty good principles; they are of permanent value. Are they not as good now, the disciples might have said, as they were when Jesus was alive? “Our Father which art in heaven.” Is not that a good way of addressing God? May not God be our Father even though Jesus is now dead? The disciples might conceivably have come to such conclusions. But certainly nothing could be more unlikely. These men had not even understood the teachings of Jesus when he was alive, not even under the immediate impact of that tremendous personality. How much less would they understand after he had died, and died in a way that indicated hopeless failure! What hope could such men have, at such a time, of influencing the world? Furthermore, the hypothesis has not one jot of evidence in its favor. Christianity never was the continuation of the work of a dead teacher.

It is evident, therefore, that in the short interval between the death of Jesus and the first Christian preaching, something had happened. Something must have happened to explain the transformation of those weak, discouraged men into the spiritual conquerors of the world. Whatever that happening was, it is the greatest event in history. An event is measured by its consequences—and that event has transformed the world.

According to modern naturalism, that event, which caused the founding of the Christian Church, was a vision, an hallucination; according to the New Testament, it was the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. The former hypothesis has been held in a variety of forms; it has been buttressed by all the learning and all the ingenuity of modern scholarship. But all to no purpose! The visionary hypothesis may be demanded by a naturalistic philosophy; to the historian it must ever remain unsatisfactory. History is relentlessly plain. The foundation of the Church is either inexplicable, or else it is to be explained by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. But if the resurrection be accepted, then the lofty claims of Jesus are substantiated; Jesus was then no mere man, but God and man, God come in the flesh.

We have examined the liberal reconstruction of Jesus. It breaks down, we have seen, at least at three points.

It fails, in the first place, in trying to separate divine and human in the Gospel picture. Such separation is impossible; divine and human are too closely interwoven—reject the divine, and you must reject the human too. Today the conclusion is being drawn. We must reject it all! Jesus never lived! Are you disturbed by such radicalism? I for my part not a bit. It is to me rather the most hopeful sign of the times. The liberal Jesus never existed—that is all it proves. It proves nothing against the divine Savior. Jesus was divine, or else we have no certain proof that he ever lived. I am glad to accept the alternative.

In the second place, the liberal Jesus, after he has been reconstructed, despite his limitations is a monstrosity. The Messianic consciousness introduces a contradiction into the very center of his being; the liberal Jesus is not the sort of man who ever could have thought that He was the Messiah. A humble teacher who thought he was the Judge of all the earth! Such an one would have been insane. Today men are drawing the conclusion; Jesus is being investigated seriously by the alienists. But do not be alarmed at their diagnosis. The Jesus they are investigating is not the Jesus of the Bible. They are investigating a man who thought he was Messiah and was not Messiah; against one who thought he was Messiah and was Messiah they have obviously nothing to say. Their diagnosis may be accepted; perhaps the liberal Jesus, if he ever existed was insane. But that is not the Jesus whom we love.

In the third place, the liberal Jesus is insufficient to account for the Origin of the Christian Church. The mighty edifice of Christendom was not erected upon a pin-point. Radical thinkers are drawing the conclusion. Christianity, they say, was not founded upon Jesus of Nazareth. It arose in some other way. It was a syncretistic religion; Jesus was the name of a heathen god. Or it was a social movement that arose in Rome about the middle of the first century. These constructions need no refutation; they are absurd. Hence comes their value. Because they are absurd, they reduce liberalism to an absurdity. A mild mannered rabbi will not account for the origin of the Church. Liberalism has left a blank at the beginning of Christian history. History abhors a vacuum. These absurd theories are the necessary consequence; they have simply tried to fill the void.

The modern substitute for the Jesus of the Bible has been tried and found wanting. The liberal Jesus—what a world of lofty thinking, what a wealth of noble sentiment was put into his construction! But now there are some indications that he is about to fall. He is beginning to give place to a radical skepticism. Such skepticism is absurd; Jesus lived, if any history is true. Jesus lived, but what Jesus? Not the Jesus of modern naturalism! But the Jesus of the Bible! In the wonders of the Gospel story, in the character of Jesus, in his mysterious self-consciousness, in the very origin of the Christian Church, we discover a problem, which defies the best efforts of the naturalistic historian, which pushes us relentlessly off the safe ground of the phenomenal world toward the intellectual abyss of supernaturalism, which forces us, despite the resistance of the modern mind, to recognize a very act of God, which substitutes for the silent God of philosophy the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who, having spoken at sundry times and in diverse manners unto the fathers by the prophets, hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son.

The resurrection of Jesus is a fact of history; it is good news; it is an event that has put a new face upon life. But how can the acceptance of an historical fact satisfy the longing of our souls? Must we stake our salvation upon the intricacies of historical research? Is the trained historian the modern priest without whose gracious intervention no one can see God? Surely some more immediate certitude is required.

The objection would be valid if history stood alone. But history does not stand alone; it is confirmed by experience.

An historical conviction of the resurrection of Jesus is not the end of faith, but only the beginning; if faith stops there, it will probably never stand the fires of criticism. We are told that Jesus rose from the dead; the message is supported by a singular weight of evidence. But it is not just a message remote from us; it concerns not merely the past. If Jesus rose from the dead, as he is declared to have done in the Gospels, then he is still alive, and if he is still alive, then he may still be found. He is present with us today to help us if we will but turn to him. The historical evidence for the resurrection amounted only to probability; probability is the best that history can do. But the probability was at least sufficient for a trial. We accepted the Easter message enough to make trial of it. And making trial of it we found that it is true. Christian experience cannot do without history, but it adds to history that directness, that immediateness, that intimacy of conviction which delivers us from fear. “Now we believe, not because of thy saying: for we have heard him ourselves, and know that this is indeed the Christ, the Savior of the world.”

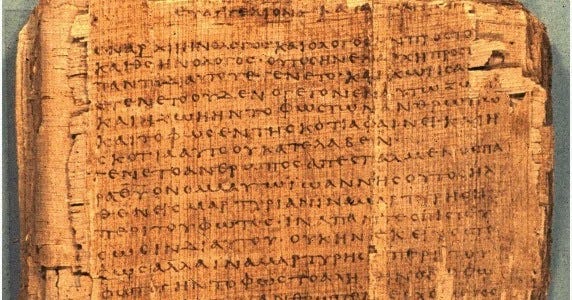

The Bible, then, is right at the central point; it is right in its account of Jesus; it has validated its principal claim. Here, however, a curious phenomenon comes into view. Some men are strangely ungrateful. Now that we have Jesus, they say, we can be indifferent to the Bible. We have the present Christ; we care nothing about the dead documents of the past. You have Christ? But how, pray, did you get him? There is but one answer; you got him through the Bible. Without the Bible you would never have known so much as whether there be any Christ. Yet now that you have Christ you give the Bible up; you are ready to abandon it to its enemies; you are not interested in the findings of criticism. Apparently, then, you have used the Bible as a ladder to scale the dizzy height of Christian experience, but now that you are safe on top you kick the ladder down. Very natural! But what of the poor souls who are still battling with the flood beneath? They need the ladder too. But the figure is misleading. The Bible is not a ladder; it is a foundation. It is buttressed, indeed, by experience; if you have the present Christ, then you know that the Bible account is true. But if the Bible were false, your faith would go. You cannot, therefore, be indifferent to Bible criticism. Let us not deceive ourselves. The Bible is at the foundation of the Church. Undermine that foundation, and the Church will fall. It will fall, and great will be the fall of it.

Two conceptions of Christianity are struggling for the ascendancy today; the question that we have been discussing is part of a still larger problem. The Bible against the modern preacher! Is Christianity a means to an end, or an end in itself, an improvement of the world, or the creation of a new world? Is sin a necessary stage in the development of humanity, or a yawning chasm in the very structure of the universe? Is the world’s good sufficient to overcome the world's evil, or is this world lost in sin? Is communion with God a help toward the betterment of humanity, or itself the one great ultimate goal of human life? Is God identified with the world, or separated from it by the infinite abyss of sin? Modern culture is here in conflict with the Bible. The Church is in perplexity. She is trying to compromise. She is saying, “Peace, peace,” when there is no peace. And rapidly she is losing her power. The time has come when she must choose. God grant she may choose aright! God grant she may decide for the Bible! The Bible is despised—to the Jews a stumbling block, to the Greeks foolishness—but the Bible is right. God is not a name for the totality of things, but an awful, mysterious, holy Person, not a “present God,” in the modern sense, not a God who is with us by necessity, and has nothing to offer us but what we have already, but a God who from the heaven of his awful holiness has of his own free grace had pity on our bondage, and sent his Son to deliver us from the present evil world and receive us into the glorious freedom of communion with himself.

This essay first appeared in The Princeton Theological Review, Vol. 13, 1915. In May of that year, it served as Machen’s inaugural address at the time of his installation as Assistant Professor of New Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary.

FOR FURTHER READING

J. Gresham Machen: Selected Shorter Writings, ed. by D. G. Hart. This volume includes “History & Faith,” along with 45 other important essays by Machen.

“A Vote of Thanks to Cyrus,” by Dorothy Sayers. You can find this essay in her book Unpopular Opinions, and in a more recent collection of Sayers’ writings titled, Letters to a Diminished Church.

Jesus & The Eyewitnesses, by Richard Bauckham. Be sure to get a copy of the Second Edition (released in 2017) which includes three additional concluding chapters. For beginners, I’d recommend starting with Bauckham’s book, Jesus: A Very Short Introduction.

Introductory Lessons on Christian Evidences, by Richard Whately. This book was first published in 1837, and a PDF copy is available here.

Evidences of the Authenticity, Inspiration & Canonical Authority of the Holy Scriptures, by Archibald Alexander (a PDF copy of this 1836 book can be found here).

Exodus: Myth or History?, by David Rohl

Is Jesus History?, by John Dickson

Can We Trust the Gospels?, by Peter J. Williams