What's the Point of Jesus' Parable of The Rich Man & Lazarus?

Hint: This famous story might not mean what you think it means!

In Luke 16, Jesus tells a captivating story about two contrasting characters: one who lives in luxury, and another man outside his gate, covered in sores. Unlike Jesus’ other parables, one of these characters is given a name. The poor man in this story is called Lazarus, and as you make your way into the parable, it almost appears as if the rich man suffers in the afterlife because of his great wealth, and that Lazarus is comforted as a result of his poverty. In verse 25, for example, Abraham says to the rich man, “Child, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish.”

The odd thing about this way of framing the story, however, is that in Genesis 13:2-6, Abraham is himself described as a wealthy man. He was “very rich in livestock, silver, and gold,” and his possessions were so great that “he wasn’t able to stay together with his cousin Lot as they entered the promised land because the land could not support both of them with all their flocks, herds and tents.” So, in light of this reality, how are we to make sense of this parable? If Abraham was rich in his lifetime, shouldn’t he, too, be forced to suffer in the afterlife?

There are other difficulties with this story as well. For example, according to Daniel 12, at the time of the end, “many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.” Yet, in Jesus’ parable, no one appears to be sleeping as they await the promise of a future resurrection. In fact, everyone seems to be fully conscious and awake already. Finally, the geography of the afterlife is overly simplistic. Heaven and hell appear to be adjacent to one another, separated only by a wide chasm. They are so close in fact that Abraham and this rich man can carry on a lengthy conversation. As a result of all this, I am convinced with those who conclude that this is not a literal depiction of the afterlife, but is merely a story Jesus tells in order to make a point.

The Parable In Its Broader Context

First of all, I think it is important to read Luke 16 in light of its own historical context. In other words, how would Jesus’ story be received by members of his original audience? According to Richard Bauckham, the tale Jesus tells was, in the first century, a familiar one.1 There are not only Jewish versions of this story, but also Egyptian and Greco-Roman versions as well. Across all the iterations, the general outline of the story is rather similar. A rich man and a poor man die (usually on the same day), and in the afterlife, they experience a kind of reversal of fortune.

It is somewhat like the popular Charles Dickens’ classic tale, A Christmas Carol. Because of the popularity of this story, most of us are familiar with its characters and plot line. Now, imagine for a moment that you decided to see A Christmas Carol at your local theatre and that you soon discovered it was a loose adaptation with a variety of political overtones. What would you think, for example, if Ebenezer Scrooge looked and sounded a lot like a famous contemporary politician? What if little catch phrases sprinkled in here and there began to make it clear that this version of the play was designed to make a political point? Well, in such a case, your reaction to the story would depend a lot on your political persuasion. If you found that your favorite politician was the one being criticized, you would no doubt be shocked, but if the one being criticized was your favorite political villain, you might find yourself cheering along.

The Parable In Its Biblical Context

Though the analogy is far from perfect, I think it might give us a hint of what is happening in Luke 16. Jesus tells this well-known story about two characters whose fortunes are reversed in the afterlife, not to give us a literal description of heaven and hell, but to comment on the complete and utter blindness of Israel’s corrupt leadership. This could help to explain why the parable gives the impression that the rich man goes to Hades simply because he was wealthy. Jesus was not promoting that view of salvation, but was adapting a popular story which originally did promote that perspective. So then, how should we read and evaluate this parable? Well, if Jesus is retelling a well-known story, I suggest we look at how he adapts and changes the key elements of this famous tale.

In Lk 16:19, Jesus says, “There was a rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day.” Because we live in a very affluent culture, I think we often miss the point of this verse. Though purple is relatively common in our own day, it was actually quite rare and hard to come by in first-century Judea, which is why it is typically associated with royalty. For example, in the book of Esther, when Mordecai was elevated to the king’s right hand, we are told in chapter 8 that he was given “a robe of fine linen and purple.” We could also think of a text such as Lk 7:24-25 in which Jesus asked the crowd about John the Baptist: “What did you go out into the wilderness to see? A man dressed in soft clothing? Behold, those who are splendidly clothed and live in luxury are found in kings’ courts!”

The rich man of Jesus’ parable is described in a similar way. According to Jesus, these not only point to his great wealth but also his power and prestige. This man is clothed in purple and fine linen, and feasts sumptuously every day. In other words, he might not only be rich, but more likely than not, he is a man of nobility as well. Yet there is another connection that we are likely to miss. In the first century, kings and emperors were also priests. In fact, one of the titles of the Roman Emperor was “Pontifex Maximus,” which means “the highest priest.” In Judea, however, though the priesthood had always been kept distinct from the office of kingship, it was no less royal.2

Josephus indicates that, in the first century, it was common for the daughters of the high priests to be given in marriage to members of the Herodian dynasty.3 That is because both the Herodians and the high priests were considered to be royal office bearers. With this in mind, we should also recall that the garment of the high priest was to be made of “blue and purple and scarlet yarns, and of fine twined linen” (Ex 28:8). Josephus describes a scene in which all the Levitical priests wore white garments made of “fine linen, while the high priest was arrayed in purple and scarlet clothing.”4 With all this background information, at the very least, it seems possible that Jesus is not only describing a wealthy man, but perhaps even a royal office bearer, or the high priest himself.

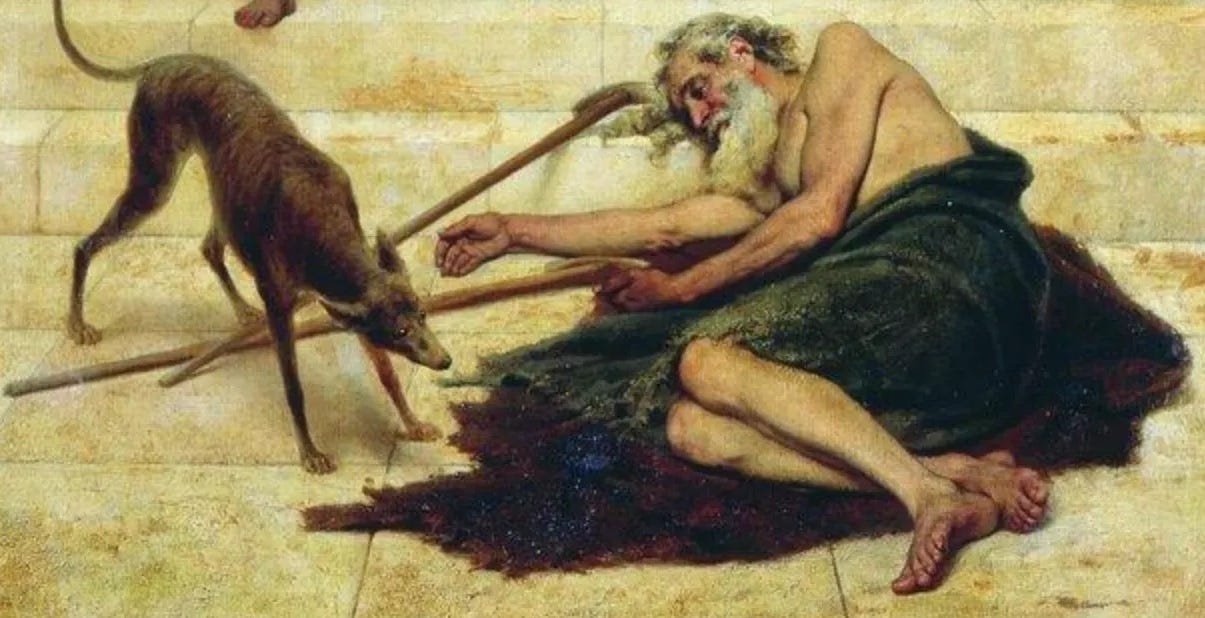

In Lk 16:20-21, Jesus says, “At this man’s gate was laid a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores, who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, even the dogs came and licked his sores.” As a rule, Jesus speaks in generalities in his parables, but here we find an exception to this rule as Jesus calls this poor man “Lazarus,” which is a short form of the name Eleazar, which means “God helps.” This was a very common name in first-century Judea, and it certainly appears to be an apt name for this particular character, who was not helped at all by the rich man but who was finally helped by God in the afterlife. This may be one of those small differences that Jesus introduces in order to contrast his version of the story with other popular versions. For example, in the Rabbinic version of this popular tale, what is often emphasized is the wickedness of the rich man in contrast to the righteousness of the poor man, but this kind of moralizing is completely absent from Jesus’ story. Perhaps by naming the poor man, Lazarus, Jesus is revealing to us that salvation is by grace. God does not help those who help themselves—no, God helps completely helpless people, like Lazarus.

Now, according to Jesus’ parable, Lazarus was comforted at Abraham’s side when he died, whereas the wealthy man clothed in purple and fine linen was tormented. It is interesting that in verse 24 the rich man calls out saying, “Father Abraham, have mercy on me,” particularly when contrasted with the meaning of Lazarus’ name. God has mercy on whom he will have mercy—he is the one who helps—and yet, what do we find the rich man doing? He does not ask God for help, but is found praying to a saint! In other words, even amid his great turmoil, God remains far from his heart. Many Jews of this period did place their trust in Abraham, whose merit was viewed as the root and source of their salvation.5 But as you look closely at the promises revealed to this founding patriarch, it was not in Abraham himself, but in his seed, that the world would one day be blessed.6

When the rich man is told that nothing can be done to change his fate, he says in verses 27–28, “Then I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my father’s house—for I have five brothers—so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.” Here again, Jesus has added his own unique material to the popular morality tale. In particular, he says that this rich man has “a father and five brothers.” That is oddly specific language.

Insight from the First-Century Context

According to Josephus and three of the four Gospel writers, Caiaphas was Israel’s high priest during the days of Jesus’ earthly ministry.7 Further, as it turns out, he was the son-in-law of Annas, who had also reigned as high priest some years earlier, and who seemed more than a little reluctant to relinquish his power (which is why Luke ended up describing the high priesthood in Jesus’ day as a kind of co-regency between both Annas and Caiaphas). Josephus goes into much more detail about these characters, saying for example that Annas (also spelled Ananus), “was a most fortunate man; for he had five sons, who had all performed the office of a high priest to God, and he had himself enjoyed that dignity a long time formerly, which had never happened to any other of our high priests.8

According to Jn 18:15-16, Caiaphas lived in a “gated” home, and in his role as high priest, he wore purple and fine linen. We also know that he was the son-in-law of Annas, who had five sons of his own. When we take a close look at the additional material that Jesus adds to this well-known morality tale, things seem to match up amazingly well with what we know about the high priestly family that was actually in power in his day.

In verse 29, Abraham refuses the rich man’s request to send Lazarus to the house of his father to warn his five brothers, saying, “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.” The rich man then says, “No, father Abraham, but if someone goes to them from the dead, they will repent.” Abraham then responds in verse 31 by saying, “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.”

Not only does Jesus’ parable significantly differ from the popular morality tale told by the Rabbis of his day, but by the time you get to the end of the parable, there is just no hope at all for the man dressed in purple, or for any of the members of his family. According to Bauckham, Jesus’ parable “describes the fate of particular individuals after death, proposes a way in which this fate could have become known to the living, but then rejects it.” To return to the analogy at the beginning, imagine seeing a version of A Christmas Carol in which Ebenezer Scrooge stubbornly refused to heed the warnings of all his ghostly visitors. What if we found him instead alone on Christmas morning, counting his money? Though it wouldn’t warm anyone’s hearts, an ending like that certainly wouldn’t fail to catch your attention! Similarly, Bauckham says that the original hearers of Jesus’ story “would expect the rich man’s request to be granted.” Shockingly, however, the request was denied. Why is this? Because, according to Jesus, even if someone were to come back from the dead, these particular men are so stubborn that even in a case like this, they would still refuse to repent.

Since the rich man was told that his father and five brothers had the writings of “Moses and the prophets,” we should consider what those texts actually said on some of these matters. In the first place, many of the members of the high-priestly families were of the Sadducee party, which, as a rule, did not believe in the afterlife. Yet, according to Moses, when Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob died, they were “gathered to their people.”9 The prophet Daniel says that at the end of the age, those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake” (Dan 12:1-2). And what had Moses and the Prophets said about caring for the poor? According to Dt. 15:7, “If one of your brothers should become poor, in any of your towns…you shall not harden your heart or shut your hand against your poor brother.” And Is 3:14 says, “The LORD will enter into judgment with the elders and princes of his people: It is you who have devoured the vineyard, the spoil of the poor is in your houses.”

Ezekiel addresses this same theme in chapter 34 of his prophecy:

Son of man, prophesy against the shepherds of Israel, prophesy, and tell them, even to the shepherds, Thus says the Lord Yahweh: Woe to the shepherds of Israel who feed themselves! Shouldn’t the shepherds feed the sheep? You eat the fat, and you clothe you with the wool, you kill the fatlings; but you don’t feed the sheep. You haven’t strengthened the diseased, neither have you healed that which was sick, neither have you bound up that which was broken, neither have you brought back that which was driven away, neither have you sought that which was lost; but with force and with rigor have you ruled over them. They were scattered, because there was no shepherd; and they became food to all the animals of the field, and were scattered. My sheep wandered through all the mountains, and on every high hill: yes, my sheep were scattered on all the surface of the earth; and there was none who searched or sought…Behold, I am against the shepherds; and I will require my sheep at their hand…and I will deliver my sheep from their mouth, that they may not be food for them. For thus says the Lord Yahweh: Behold, I myself, even I, will search for my sheep, and will seek them out (Ezk 34:1-11).

In John 10, Jesus claims to be Israel’s true shepherd, which is to say, he was claiming to be Yahweh and when many of the Jewish leaders began testing him and saying things such as, “He has a demon,” Jesus responded to them by saying, “You do not believe because you are not among my sheep. My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me” (v. 20-27). In other words, his mission was not merely to seek and save the lost, but also included the judgment of Israel’s unrepentant false shepherds.

Concluding Observations

What is amazing about Jesus’ parable of the rich man and Lazarus is that it is not only a story that happened to be pregnant with meaning, particularly to all his first-century Jewish hearers, but it also ended up being a kind of prophecy of things to come. We have just discussed John chapter 10 in which Jesus claims to be the good shepherd of Israel, fulfilling the promise of Ezekiel and other prophets. What ends up happening in the next two chapters of John’s Gospel? As it turns out, a man by the name of Lazarus dies, and after a few days, is brought back to life by Jesus. In fact, according to Jn 11:45, many of the Jews who witnessed this miracle began to believe in Jesus.

Unfortunately, this did not sit well with the high priests, because Jn 12:10 informs us that “they made plans to put Lazarus to death as well.” Here we find not only a lack of repentance and a stubborn refusal to believe in Jesus, but also a dark and active hostility to his messianic mission that had been announced centuries in advance by the Hebrew prophets of old. But all this had been announced in advance by Jesus in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus.

In their deep hatred and opposition, these false shepherds would eventually have Jesus arrested, tried, and condemned. Then, on the Eve of Passover, he would be beaten, scourged, and crucified—not for his own sins, but for yours and mine. What they meant for evil, God meant for our good. The high priests of Israel were arrayed in royal splendor, and their beautiful garments were merely symbolic of the magnificence and perfection of the one true prophet, priest, and king who in the fullness of time would come to shepherd his people. As our final prophet, he speaks to us in his word, saying, “My sheep hear my voice.” As our great and final priest, he says, “The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.” And as our true and ultimate king, he says, “I know my sheep, and they follow me.”

Even if one should rise from the dead, not everyone will be persuaded. For all the “proudly exultant ones” (Zph 3:11) who stubbornly fail to confess and acknowledge their sin, and for all those who refuse to turn from their sin to the crucified and risen Lord, he will say, “you are not of my sheep.” But if the Lord is your shepherd, he will lead you beside still waters and make you lie down in green pastures. He will restore your soul. And even though this world becomes increasingly dark and filled with unspeakable evil, we will not fear, for God is with us. Surely goodness and mercy shall follow us all the days of our lives.

UPDATE: After a lengthy discussion of the first-century context, T.C. Schmidt advocates this same interpretation of Jesus’ parable from Luke 16 in his new book, Josephus & Jesus (Oxford University Press, 2025).

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast, which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Logia, Core Christianity, Beautiful Christian Life, and many others. His forthcoming book, Luke’s Key Witness, is due out later this year. An earlier version of this article was published at The Heidelblog, which you can find here.

Related Episodes

Rethinking the Parables of Jesus, HS #43 with Scott Churnock

Simply Genius, HS #62 with Peter J. Williams (on Jesus’ Parables)

Jacob’s Ladder, HS #63 with Richard Bauckham, Michael Horton, et al

Recent Articles

A Pre-70 Date for Revelation? Shane Rosenthal

A Pre-70 Date for the Gospels & Acts, Shane Rosenthal

The Implications of 70 AD on the Date of the Gospels & Acts, Shane Rosenthal

The Date of John’s Gospel, Revisited, Shane Rosenthal

New Evidence for a Historical Moses? Shane Rosenthal

Simon of Cyrene: An Archaeological Discovery, Shane Rosenthal

Luke’s Key Witness? Shane Rosenthal

Richard Bauckham, The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses. Supplements to Novum Testamentum, V. 93 (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 97–118.

For example, 1Pt 2:9 refers to New Testament saints as “a royal priesthood.” In short, he’s using old covenant imagery to describe new covenant realities.

Josephus, Ant. 15.9.3; 17.1.2; 17.3.2; 18.5.1–4.

Josephus, Ant. 11:331.

See Targum Ps. Jonathan Gen 26:24, Dt. 2:19; Targum Neofiti, Gen 26:24, Num 23:9, Est 1:2, 5:1.

Gen 22:17-18, 26:4, Gal 3:15-18.

Josephus, Ant. 18.2.2, 18.4.3; cf. Mt 26:3, Lk 3:1-2, Jn 18:13.

Josephus Ant. 20.9.1

Gen 25:8, 17, 35:29, 49:29, 33.

Although not raised in this piece, the meaning of the parable seems to refute Calvinism.

I had forgotten one of the most important tenants of hermeneutics, that being that we must consider the audience and culture to whom the message was intended. The reconnection to meta story and raising of Lazarus helped me to see the consistency of the Lord’s message of faith in him alone is what saves us and my own Spiritual growth is completely tied to this reality. Very helpful stuff brother..........