Acts 2 & The Tongues Controversy

According to the Mishna, first-century Jews distinguished between Hebrew, "the holy tongue," and "other tongues" such as Greek and Aramaic. Can this inform our reading of Acts 2?

Note: I recently expanded this article into a 26-page downloadable PDF document that explores the origins of Pentecostalism, and provides a careful analysis of every passage in the New Testament related to the subject of tongues. Click here for more info.

In his inaugural sermon on the day of Pentecost, the apostle Peter stood in the courtyard of the Jerusalem Temple and proclaimed Jesus of Nazareth as the fulfillment of all the Old Testament promises and expectations related to the coming Messiah. By his death, burial, and resurrection, he secured the forgiveness of sins for his people, as well as for all those “who are far off” (v. 39).

But this passage also happens to be one of the foundational texts for what has come to be known as “Pentecostalism,” a movement that began in the early part of the twentieth century, and which according to one dictionary “emphasizes a post-conversion ‘baptism in the Holy Spirit’ for all believers, with glossolalia (speaking in tongues) as the initial evidence of such baptism.”1 That same dictionary defines glossolalia as “the supernatural ability to speak in languages not previously learned…as happen[ed] on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2).” But there’s a foundation question that I’d like us to step back and ask right at the outset. Does a clear reading of Acts 2 actually promote any of these beliefs?

I’m actually convinced that the Bible encourages a kind of healthy skepticism. Paul calls us to “test everything,” while also reminding us to “hold on to the good” (1Th. 5:21). This advice is especially important to consider whenever we encounter different interpretations of Scripture. We should test all things, including the beliefs and interpretive assumptions of our own traditions. After all, it’s easy to believe that our ideas about the Bible are essentially correct and that all those other people out there in those other denominations are the ones who are wrong-headed, but it takes a great deal of humility and self-reflection to consider the possibility that we may be the ones who have “[wrongly] handled the word of truth” (2Tim 2:15). This is why it’s so important for us to be careful not to read our theological beliefs into a given passage (eisegesis), but that all of us work hard to ensure that our interpretations are rooted in and derived from the text of Scripture itself (exegesis).

So, what does Luke actually say about “tongues” in Acts chapter 2? Well, the first time this word actually appears in the passage, it refers not to the organ of speech but to the appearance of “tongues of fire” (2:3). This visible sign was also accompanied by a sound from heaven “like a mighty rushing wind” (2:2). In my thinking, these two verses indicate that there was definitely something unique going on at this particular moment in redemptive history. Though it’s common for Pentecostal interpreters to claim that Acts 2 relates to the normative experience of the church across all ages, I’m simply not aware of any churches claiming to have received these sign-gifts today, or at any time in church history for that matter. Think about this for a minute. If the Pentecostal interpretation of Acts 2 holds true, why should we limit “the gift of tongues,” merely to linguistic phenomena? Shouldn’t we also expect the Holy Spirit to give visible signs of his presence through “tongues of fire” as well? The fact that there haven’t been reports of this sort of thing since the day of Pentecost is a strong indication to me that the signs recorded in Acts 2 should not be taken as normative.

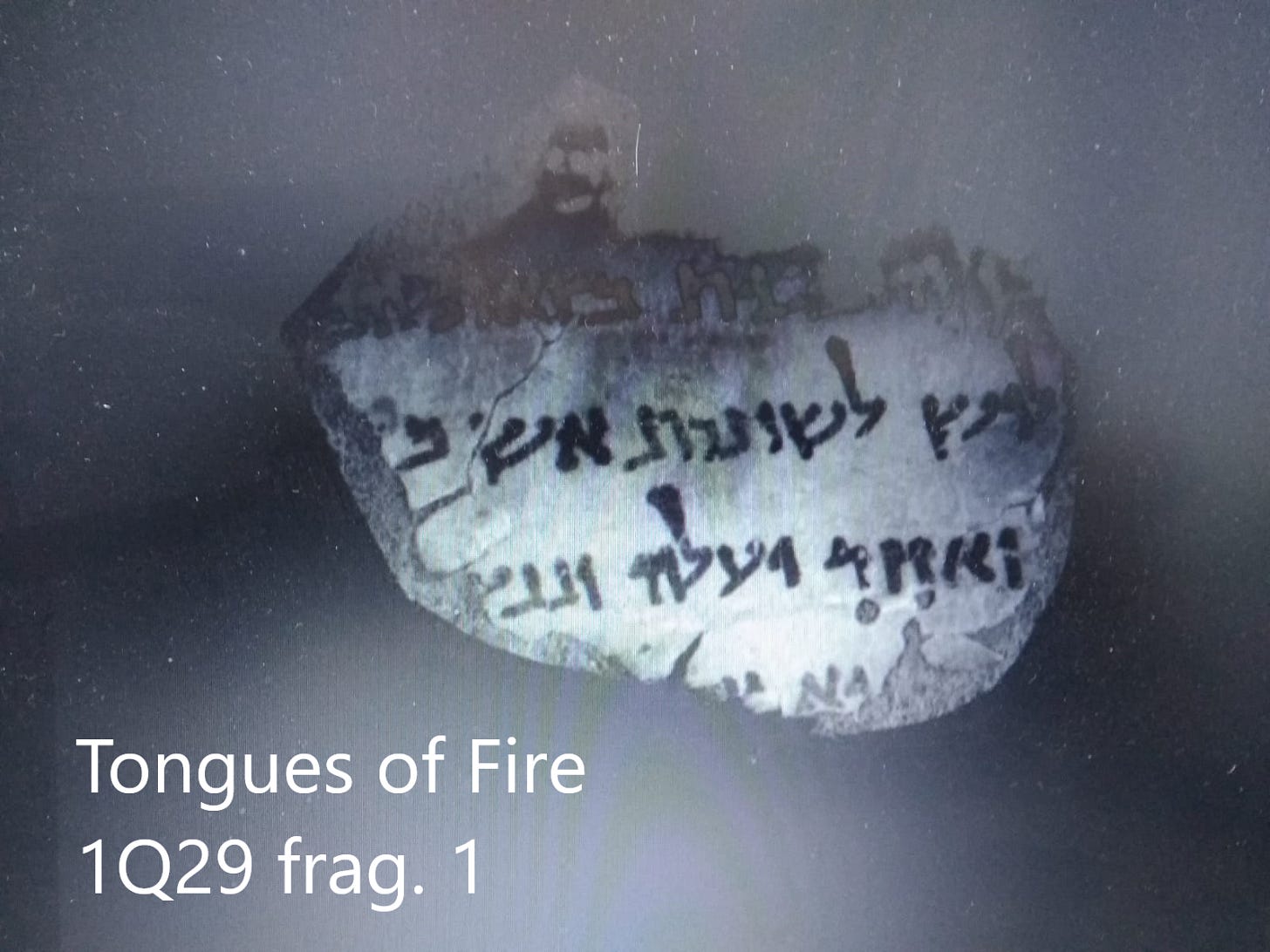

It’s interesting to note that the phrase “tongues of fire” actually appears in a few Dead Sea Scroll fragments. These ancient Jewish texts from before the time of Christ give us a fascinating account of the Urim and Thumin, which according to various Old Testament passages gave direction in specific situations to Israel’s priests and prophets.2 In a legible section of one of these fragments, we read: “The Urim...shall give you light, and it shall come forth with tongues of fire...and you shall observe...all that the prophet shall say to you...”3 So, in this ancient Jewish passage, “tongues of fire” seem to be associated with the idea of prophetic inspiration. This is particularly relevant for the study of Acts chapter 2, which also happens to relate to prophetic inspiration. As Peter himself explains, the prophet Joel had predicted a time in which God would pour out his Spirit on all flesh, causing Israel’s sons and daughters to “prophesy” (2:17-18).

In Acts 2:4, Luke went on to say that the disciples were then “filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance.” So what is the meaning of the phrase, “other tongues,” which Luke uses here? Are the apostles having strange ecstatic experiences in a language unknown to themselves or others? Actually, when we examine the larger context, it becomes obvious that the words of the apostles were clearly heard and understood. So what’s really going on in this passage? What does it mean to say that the disciples spoke in “other tongues”?

The phrase “other tongues” appears in the Greek translation of Isaiah 28:11 which specifically relates to those who spoke in a foreign language. Paul cites this passage in 1Cor 14:21, and it’s clear that his definition is the same as Isaiah’s. This phrase is also found in a number of Jewish texts in which Hebrew is described as a “holy tongue” in contrast to other “foreign tongues.” For example, in the Book Sirach, we’re told, “For the things translated into “other tongues,” have not the same force in them when uttered in Hebrew.”4 Similarly, in the Mishna, which is the oldest section of the Talmud, we find this:

The following ritual texts may be recited in other tongues...the tithing declaration, chanting the Shema...grace after meals, the oath of testimony...The following ritual texts must be recited in the Holy Tongue: the declaration of first fruits...the original blessings and curses, the priestly benediction, the blessing of the high priest...etc.5

Not only does this section of the Mishna help us to see that ancient Jews contrasted the holy tongue with foreign tongues, but it also makes clear that Hebrew was to be exclusively used during “the declaration of first fruits,” which was the sacred liturgy associated with the Feast of Pentecost. In other words, in Acts 2, the crowds which gathered at the Jerusalem Temple would have expected religious services presented in Hebrew, which by this time in Israel’s history had become a kind of sacred language that was only half understood. But what they ended up hearing that morning were powerful messages about Jesus in other tongues (i.e., in common ordinary languages such as Greek and Aramaic).

There’s something else worth pointing out in verse 4 as well. Luke says the disciples were “filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.” If you notice, Luke doesn’t actually describe “other tongues” in this verse as a gift of the Spirit. It’s certainly true that they spoke in other languages, but according to this verse, the Spirit’s unique gift was specifically related to “utterance,” which in Greek (apophthegomai) is actually quite a rare word. In fact, it only appears a handful of times in the Greek New Testament and the Septuagint combined. One of the most frequently used Greek lexicons defines this word as follows: “To express oneself orally…[to] speak out, declare boldly or loudly...” In particular, it has reference to “the speech of a wise man [or] an oracle-giver, diviner, prophet, exorcist, and other inspired persons.”6 As an example, this word appears in the Greek translation of 1Ch 25:1 in which David sets apart various men “who had prophesied,” and Josephus used it when speaking of those who were “conversant in the discourses of the prophets.”7

When we put all this information together, we see that in Acts 2, the Holy Spirit has empowered the disciples to speak boldly and prophetically in common everyday languages. It was a time of new revelation, and the foundation of the New Testament was being laid. Under divine inspiration, Peter proclaimed a message that was completely centered on Jesus, showing how his death, burial, and resurrection had actually been written in advance throughout the Hebrew Scriptures. In fact, this is precisely what Jesus said the Holy Spirit would inspire his disciples to do.8 This is why Christians believe the writings of the apostles are just as inspired as the writings of Moses and other Old Testament texts.

Before his ascension, Jesus instructed his disciples saying, “Stay in the city until you are clothed with power from on high” (Lk 24:49). In other words, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was to be a one-time event that took place at a specific location, rather than a recurring event that Christians should expect to take place in all subsequent times and places. Acts 2, therefore, should not be thought of as the normative experience of the church across all ages.

As we’ve seen, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost was primarily related to the gift of bold prophetic speech, rather than to the particular languages in which those speeches were delivered. The long silence of the inter-testamental period was over; God was speaking to his people once again, just as Joel had predicted. This was Luke’s primary focus as he conveyed these important events. The disciples did speak in “other tongues” that day, but I’m convinced that most of us have a wrong impression of what this actually means. As we’ve seen, it may simply refer to the fact that they spoke languages other than Hebrew there at the Jerusalem Temple. This would have been surprising to all those who had gathered that morning, since they had expected to hear a liturgical service in the holy tongue, which they only half understood. In fact, hearing something other than Hebrew was likely perceived as a little “unkosher,” which could explain why some in the crowd suggested that they were “filled with new wine” (v. 13).

Though some people there at the Temple mocked the disciples, what’s clear is that they heard and responded to intelligible words, which rules out the ecstatic utterance or private prayer language interpretation (at least when applied to Acts 2). The people in the crowd that day heard Jesus’ followers speaking in their native tongues about “the mighty works of God” (v. 11). So, were the disciples empowered by the Holy Spirit to speak languages they had never learned? The text doesn’t actually say this. What Luke does make clear, however, is the fact that Jesus’ followers spoke in languages other than Hebrew and that they were specifically empowered to speak boldly, and prophetically on that unique and memorable day.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I’ve expanded this material into a 26-page downloadable PDF document, which you can receive for a gift of any size to help support the work of The Humble Skeptic podcast. For more information about this resource, click here.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of a national radio broadcast called the White Horse Inn, which he also hosted from 2019-2021. Shane has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Core Christianity, Modern Reformation, Heidelblog, and others. Shane received an M.A. in Historical Theology from Westminster Seminary California, and he lives with his family in the greater St. Louis area.

Stanley J. Grenz, David Guretzki and Cherith Fee Nordling (editors), Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, IL, 1999), p. 90.

Cf. Ex 28:30, Lev 8:8, Num 27:21, Dt 33:8, 1Sam 14:41, 28:6, Ezr 2:63, and Neh 7:65.

Cf. 1Q29, and 4Q376

Sirach 0:20 (KJV Apocrypha)

Mishna, Sota 7:1-2 (see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lashon_Hakodesh). A special word of thanks to Robert Zerhusen for bringing this passage of the Mishna to my attention way back in the early 90s, and for introducing me to Clyde McCone’s super helpful book, Culture & Controversy: A New Investigation of the Tongues of Pentecost (1978). If you’re interested in studying this topic further, Robert has written a very helpful essay titled, A New Look at Tongues.

A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature (BDAG - Third edition).

Josephus, War 2:159 (2.8.12). See also Philo, Moses 2:263.

Cf. Lk 24:49, Jn 14:26, 15:26-27, Acts 1:4-5.