Can We Trust Luke's History of the Early Jesus Movement?

A handful of fascinating clues from Acts 18 indicate that we not only can, but should.

Acts 18 tells the story of Paul’s visit to Corinth sometime in the late 40s to early 50s. This date is fairly secure, given that Luke refers to Claudius’ expulsion of the Jews from Rome, which is known from other sources to have taken place around 49 AD.1 Later in that same chapter, Luke goes on to say that while Paul was in Corinth, certain Jews sought to have him arrested and brought before the tribunal of Gallio, the proconsul of Achaia.2

Sometime in the mid-1850s, Cambridge scholar J.B. Lightfoot gave a series of lectures on the book of Acts in which he argued that the reference to Gallio was “Another instance of St. Luke’s accuracy.”3 How so? First of all, he argues that Achaia, which is the specific region in Greece where Corinth was situated, “had originally been a senatorial province. Tiberius took it from the Senate in A.D. 15.4 Claudius in A.D. 44 gives it back to the Senate.5 Thus between A.D. 15-44 the term that Luke uses here, ‘proconsul’ (anthupatos)…would be inappropriate.” In other words, if Luke had used this word to describe a proconsul of the region less than a decade earlier, Lightfoot is saying that would have been the wrong title for a person in Gallio’s position. But by the time that Paul arrived in the region, it was a perfect fit.

But is there any evidence that corroborates Luke’s assertion that a man by the name of Gallio served as the proconsul of Achaia outside the book of Acts itself? In his commentary, Lightfoot argued that Luke was most likely referring to a man by the name of “Lucius Junius Gallio,” who happened to be the older brother of the famous Roman statesman, Seneca. Though “his proconsulship in Achaia is not directly mentioned,” Lightfoot argued that a passage from Seneca’s writings actually places him in the region around the time frame in question.6

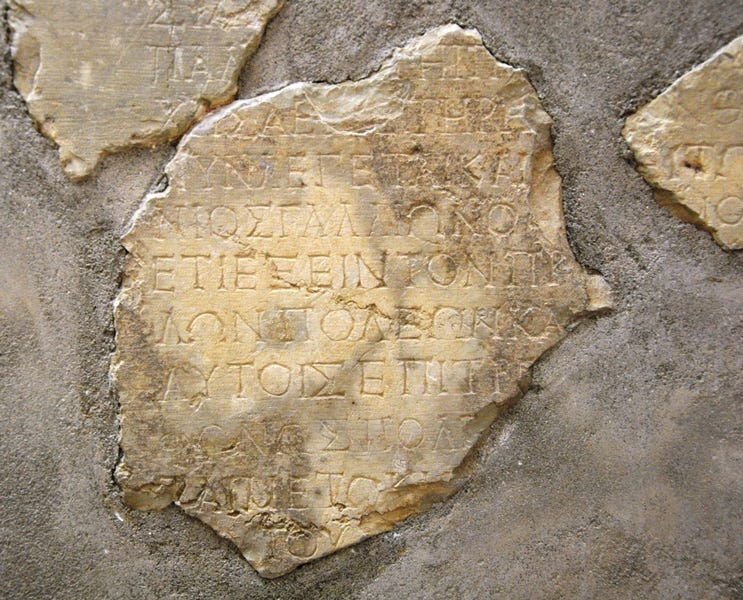

Some fifty years after Lightfoot made this argument, an archaeological discovery was made in the city of Delphi. An inscription was found (as shown in the image at the beginning of this article) that reads as follows, “Claudius Caesar…invested with tribunician power for the 12th time, and acclaimed Imperator for the 26th time…Proconsul L. Junius Gallio recently reported to me that Delphi is destitute of citizens…Therefore I order you to invite well-born people also from other cities as new inhabitants.”7

Though J.B. Lightfoot did not live to see the discovery of the famous “Gallio Inscription,” he made quite a well-educated guess with the limited information he had. As it turns out, he was right on the money. The Gallio mentioned in Acts 18 was in fact the older brother of Seneca who traveled to Achaia in order to begin his post as proconsul.

In his amazingly well-researched work, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, Colin Hemer argues that this archaeological discovery makes it “sufficiently clear” that “Gallio was proconsul in 51-52.”8 In fact, Hemer says the words of this inscription “enable us to place Paul’s presence in Corinth with a high probability of accuracy.”9 It also gives external confirmation for the specific details of Luke’s account and provides us with an anchor for his timeline of events. Since Luke reports that Paul met Aquila and Priscilla in Corinth not long after Claudius evicted the Jews from Rome (49 AD), he would be there at precisely the right time to stand before Gallio’s tribunal.

We should keep in mind that in the first century, the internet hadn’t been invented yet, and there weren’t any handy reference works containing lists of political leaders and magistrates around the world, with annual updates and supplements. The kind of knowledge that Luke displays in Acts 18 is actually very difficult to come by. How did he know Claudius had evicted the Jews from Rome in 49 AD? How did he know that Achaia was run by a “proconsul” in those days? How did he know that a man by the name of Gallio held that office around this time? The best explanation is that Luke really was Paul’s traveling companion. He was able to get these details right because he had witnessed them firsthand.

Colin Hemer’s study of Acts is simply masterful. If you’re interested in digging into this subject, I highly recommend that you order a copy.10 As you make your way through this work, you’ll encounter compelling evidence in favor of Luke’s authenticity on just about every page. Luke’s history of the early Jesus movement is filled with countless little details, and all these obscure facts and features serve to vindicate his claim that he was really there, and that he wasn’t making stuff up.

This past March, researchers from the University of Amsterdam concluded that the best way to distinguish truth-tellers from liars was by paying close attention to the details.11 Intriguingly, Cambridge scholar Richard Bauckham has argued that a close study of the four Gospels reveals “all kinds of little details about people and places…and the controversies, all kinds of stuff about the historical context in which the stories take place. So that’s one way of verifying that the gospels are credible from that geographical, historical context that they claim to be about.”12 I’m convinced that when we apply this same approach to the book of Acts, it becomes increasingly apparent to us that Luke’s second volume really is what it claims to be. This isn’t a collection of fictional stories relating to the lives of the apostles—it’s an authentic and compelling record of the earliest days of the church, written by someone who had access to the inner circle of Jesus’ followers, and who personally witnessed many of the events described throughout his narrative.

It is certainly impressive that a consensus has emerged among New Testament scholars in recent decades to the effect that 1st Corinthians 15 includes the substance of an early Christian creed. In fact, many are persuaded that this creed goes as far back as the mid-to-early 30s.13 However, as impressive as this is, in my thinking it actually pales in comparison to the evidence we find (to give just a single example) in Acts chapter 2. Whereas Paul cited a creed that took shape within a few years of Jesus’ crucifixion, in Acts 2, Luke provides his readers with a summary of the earliest Christian sermon, delivered by Peter in Jerusalem at the Festival of Shavuot14 only fifty days removed from the death of Jesus.

Remarkably, few scholars seem to have noticed many of the fascinating parallels that exist between Peter’s inaugural sermon and the substance of the earliest Christian creed cited by Paul. Both focus on Christ’s death (Acts 2:23; 1Cor 15:3) and resurrection (Acts 2:24-31; 1Cor 15:4) as a fact attested by many living eyewitnesses (Acts 2:32; 1Cor 15:5-8), and also as something foreseen by the Hebrew prophets (Acts 2:25-28, 34-35; 1Cor 15:4-5).15 The reason for these striking parallels seems to be relatively clear. Both the creed and the sermon accurately reflect the beliefs of the earliest Christians.

Paul cited the creed in his first letter to the Corinthians around 54 AD,16 and it’s no longer controversial to argue that Luke completed the book of Acts sometime around 62 AD.17 But the important thing to highlight is the fact that both authors have presented us with accurate and reliable summaries of earlier material (Luke summarized Peter’s sermon; Paul summarized the beliefs of the early Christian community). Luke’s summary of Peter’s material, however, happens to go back just a little bit further—not merely to sometime during the first decade of the Jesus movement, but almost to the very beginning, when a little more than a hundred disciples quickly morphed into three thousand.

Of course, there isn’t a “consensus” about this sort of thing in the world of New Testament scholarship at the present moment. This is partly due to the fact that the New Testament is a collection of ancient documents that are studied in Universities around the world by scholars from a wide variety of faiths and worldview perspectives (many of which come with anti-Christian presuppositions and biases). But we should always remember that counting heads should never be viewed as more important or relevant than studying the details of Luke’s report for yourself. The more you dig into the book of Acts with the help of people like J.B. Lightfoot or Colin Hemer, the easier it will be for you to recognize the extraordinary quality of Luke’s reporting. So many of the little details he includes (not merely in chapter 18, but from just about every chapter) have now been confirmed and corroborated that the burden of proof appears to have shifted. Those who assume from the start that Acts is a work of pious fiction are the ones truly exercising blind faith. The evidence is clear—Luke is worthy of our trust.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of a national radio broadcast called the White Horse Inn, which he also hosted from 2019-2021. Shane has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Core Christianity, Modern Reformation, Heidelblog, and others. Shane received an M.A. in Historical Theology from Westminster Seminary California, and he lives with his family in the greater St. Louis area.

For Further Reading

Authenticating the Fourth Gospel, by Shane Rosenthal

Why Should We Believe the Bible?, by Shane Rosenthal

How to Detect Deception, by Shane Rosenthal

Notes

Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 25; Dio Cassius, Roman History, Book 60, Chapter 6.

See Acts 18:12-17.

Those lectures were completely lost to history until fairly recently when Lightfoot’s lecture notes were discovered at the Durham Cathedral and subsequently published under the title: The Acts of the Apostles: A Newly Discovered Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2014). The quote appears on p. 241.

Tacitus, Annals, 1.76

Suetonius, Claudius, 25.

Seneca, Epistle 104 (Lightfoot quotes him as saying, “Gallionis, qui cum in Achaia,” p. 241.

This has been edited for brevity and readability. For more information about the Gallio Inscription (also known as the Delphi Inscription), along with a complete translation, click here.

Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990), p. 168-169.

Ibid., p. 251.

Admittedly, the price is a little scary, but this does say something about its perceived value (click here to purchase).

Richard Bauckham makes this and other similar points on Episode 15: Faith Founded on Facts.

For more information, see Episode 9: The Gospel Creed.

In Greek, this festival became commonly known as “Pentecost”

See Daniel Wallace’s argument for the date of Acts here. Also, the very liberal Adolf Von Harnack arrived at a similar conclusion here. See also John A.T. Robinson’s classic work, Redating the New Testament, and Jonathan Bernier’s recent volume Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament.

So well spoken. Thanks for these valuable thoughts and references.

Have you ever heard of Heinz Warnecke? He has shown and proven beyond reasonable doubt that the island ΜΕΛΙΤΗ in Acts 28 is not Malta but Kefalonia. He cites proof from the earliest documents of Ilias and Odyssee over contemporary sources and naval history to the newest attempts of pious fraud during the last few hundred years. He'd be most ready to share his insights with you. (He has written his doctoral dissertation about this topic, published two books, written articles, and is in the process of finishing a third book about Paul's seafare and about the letters to Titus and Timothy.

So well spoken. Thanks for these valuable thoughts and references.

Have you ever heard of Heinz Warnecke? He has shown and proven beyond reasonable doubt that the island ΜΕΛΙΤΗ in Acts 28 is not Malta but Kefalonia. He cites proof from the earliest documents of Ilias and Odyssee over contemporary sources and naval history to the newest attempts of pious fraud during the last few hundred years. He'd be most ready to share his insights with you. (He has written his doctoral dissertation about this topic, published two books, written articles, and is in the process of finishing a third book about Paul's seafare and about the letters to Titus and Timothy.

So well spoken. Thanks for these valuable thoughts and references.

Have you ever heard of Heinz Warnecke? He has shown and proven beyond reasonable doubt that the island ΜΕΛΙΤΗ in Acts 28 is not Malta but Kefalonia. He cites proof from the earliest documents of Ilias and Odyssee over contemporary sources and naval history to the newest attempts of pious fraud during the last few hundred years. He'd be most ready to share his insights with you. (He has written his doctoral dissertation about this topic, published two books, written articles, and is in the process of finishing a third book about Paul's seafare and about the letters to Titus and Timothy.

https://ericmetaxas.com/watch-read/articles/paulshipwrecked/