John 5:2 "There is in Jerusalem..."

Does the grammar of John 5:2 support an early date for John's Gospel? What have scholars thought about this passage across the centuries down to the present?

John 5:2 “Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool, which in Aramaic is called Bethesda, having five roofed colonnades.”

On episode 51 of The Humble Skeptic, I featured an interview with Daniel Wallace, who argued that the grammar of John 5:2 points to a pre-70 date for the Fourth Gospel. Many scholars who start with a presupposition of a late date tend to dismiss the implications of the present-tense language of this verse by arguing that John spoke in a vivid way “as if” the area had not been destroyed. In short, he used what they refer to as a “historic present.”1

“Since [the verb “to be”] is nowhere else clearly used as a historical present,” Wallace writes in his Greek Grammar, “the present tense should be taken as indicating present time from the viewpoint of the speaker.”2 Elsewhere, he says:

I believe that exegetes would do well to not neglect what seems to be the obvious indication as to the time of writing of this Gospel. In the least, it will not do to argue, as many have, that too much weight cannot be put on the present tense. That is a judgment that can only have force if it is demonstrated that the present tense here could have a variety of forces, any one of which could plausibly view it as referring to past time. Until that happens, I would urge exegetes to take the ἐστίν more seriously in John 5:2 as a significant factor in the dating of John’s Gospel.3

I’m convinced that Daniel Wallace is on to something, particularly given that he was unable to find examples of the Greek verb “to be” used as a historic present not just in the New Testament but in any Greek text. So I decided to spend some time looking through a variety of commentaries (old as well as modern) to see what scholars across the centuries have thought about the present-tense language of John 5:2. Here are some of the highlights of my research.

See also: The Date of John’s Gospel: Are We Witnessing a Paradigm Shift?

Daniel Whitby (1709)

[I]f there is, be the true reading, as the consent of almost all the Greek copies argues, it seems to intimate that Jerusalem and this pool were then standing when St. John wrote this Gospel, and therefore that it was written, as Theophylact and others say, before the destruction of Jerusalem, and not, as the more ancient fathers thought, long after.4

Francis Atterbury (c. 1710)

“Now there is at Jerusalem…” The whole tenor of the words to my apprehension implies that the edifice with five porches (and consequently Jerusalem itself) was then standing when this passage was written.5

William Whiston (1712)

John’s Gospel [was written] A.D. 63. That this Gospel was written so early, appears highly probable to me [in light of the] following…John’s speaking of the pool of Bethesda, in the present tense is, and not was, better agrees to the time here assigned before the destruction of Jerusalem, when that pool and porch were certainly in being, than to the time afterward, when probably both were destroyed.6

Johann Bengel (1742)

John wrote before the destruction of Jerusalem. He says, there is, not was, a pool…those among the ancients who assert that this gospel was published thirty, thirty-one, or thirty-two years after our Lord’s ascension, support this view.7

John Wesley (1755)

There is in Jerusalem—hence it appears that St. John wrote his Gospel before Jerusalem was destroyed.8

Nathaniel Lardner (1756)

One argument that St. John’s gospel was written before the destruction of Jerusalem is taken from Jn 5:2, “Now there is at Jerusalem, by the sheep-market,” or sheep gate, “a pool, which is called in the Hebrew tongue Bethesda, having five porches. On this passage insist both Basnage and Lampe [that] St. John does not say, as they observe, there was, but there is. And though the pool might remain, it could not be said after the ruin of the city, that the five porches still subsisted…St. John’s speaking of the pool of Bethesda in the present tense, better agrees to the time here assigned, A. D. 68, before the destruction of Jerusalem, when that pool and porch were certainly in being, than to the time afterwards, when probably both were destroyed…[Those who say] in all probability the pool was not filled up, but was still in the same state after the destruction of Jerusalem…it might be answered that supposing the pool not to have been filled up, it would not be reasonable to think, that the porches and the gate still subsisted, after the destruction of the city.9

Henry Owen (1764)

[T]he Evangelist himself speaks of that city as still subsisting (Jn 5:2, “There is in Jerusalem”) at the time he wrote.10

Johann David Michaelis (1795)

There is a single passage in St. John’s Gospel, from which several critics have inferred that it was written before the destruction of Jerusalem. In ch. 5:2 St. John says, “There is at Jerusalem by the sheep-gate a pool, which is called in the Hebrew tongue Bethesda, having five porches.” Hence it is inferred that Jerusalem was still standing when he wrote this passage: for if Jerusalem had lain at that time in ruins, it is argued, that St. John would not have said, “There is at Jerusalem,” etc., but “There was…” But this argument appears to me at present to be less decisive than I once thought it. It is founded wholly on the single word is; but authors do not always weigh their words with so much exactness…It will be objected perhaps that St. John adds “having five porches”…but even the most correct writers are sometimes deficient in precision.11

Charles Taylor & Edward Robinson (1832)

Now there is—these words do not determine that the evangelist wrote his gospel before the destruction of Jerusalem, as has been inferred from them; for there are remains of the pool to this day…12

Samuel T. Bloomfield (1836)

[Some] appeal to Jn 5:2, “there is at Jerusalem…” as a proof that this gospel must have been written before the destruction of Jerusalem, since it recognises the city as in being when the words were written. This, others attempt to set aside by remarking that writers “do not weigh their words so exactly;” and that “the Present there may be put for the Past tense.” But the former is a frivolous excuse; and as to the latter, such a confusion of tenses cannot be admitted in a narrative…[As] to its utter and total destruction, Josephus bears testimony, in War 7.1, where he says that the whole city was so completely destroyed and dug up, “that there was left nothing to make those that came thither believe it had ever been inhabited.” With respect to…the date and the design of the Gospel, it appears most probable that it was published not very long after St. John had gone to reside at Ephesus, and only a short period before the destruction of Jerusalem—say A. D. 69.13

John Peter Lange (1871)

The ἔστι [there is] has been interpreted with reference to the porches, as indicating that, at the time of the composition of this passage, Jerusalem had not been destroyed…Yet the ἔστι may also be attributed to rhetorical vivacity.14

Frederick Godet (1879)

Bengel and Lange have concluded from the present ἔστι [there is], that the Gospel was written before the destruction of Jerusalem. But this present may be inspired by the vividness of recollection. Besides, an establishment of this kind belongs to the nature of the place and may survive a catastrophe.15

B.F. Westcott (1881)

There is at Jerusalem... The use of the present tense does not prove that the narrative was written before the destruction of Jerusalem. It is quite natural that St John in recalling the event should speak of the place as he knew it. It has indeed been conjectured that a building used for a benevolent purpose might have been spared in the general ruin, but this explanation of the phrase is improbable.16

J.B. Lightfoot (c. 1885)

The destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 was not so complete that a bath of medicinal waters should be destroyed. Indeed, it is not probable that St. John had seen Jerusalem since its fall.17 Though here Lightfoot seems to assume a post-70 date for the Gospel of John, later in his discussion of chapter 11 he writes, “This is the narrative of a person who was an eyewitness of the events he relates, and who writes not half a century later, but within a very few years of the occurrence.”18

Friedrich Blass (1907)

There is no hint [in John] of the destruction of Jerusalem (except possibly what Caiaphas says in 11:48ff.) and the saying of Jesus about the destroying of ‘this temple’ is explained by the Evangelist as about His body (2:21). Still further, in one passage (5:2) the city is expressly recorded to be still standing: “There is in Jerusalem a pool called Bethesda, having five porches.” …[T]herefore the pool was still standing in Jerusalem when the Evangelist was writing.”19

Hubert E. Edwards (1953)

Now there is in Jerusalem… Bishop Westcott’s comment on these words is a good illustration of the shifts to which a great and candid scholar may be driven by his own theory. He says: “As John recalls a familiar scene he lives again in the past, and forgets the desolation which had fallen upon the place which rises before his eyes.” Now if you were talking to an old man about the First World War, and he began a story with these words, “There is, in the city of Ypres20 a very fine building of the fourteenth century, known as the Cloth Hall,” you would think to yourself, even if you were too kind to say the words: “This old gentleman is getting very senile: he has forgotten that the Cloth Hall at Ypres was destroyed by the Germans more than thirty years ago.” But it is to such a pass as this that Bishop Westcott, and other orthodox scholars, are brought when they assume the Johannine authorship of the Gospel while still clinging to a date at the end of the century for its composition.

Notice that there are three verbs in this short verse. The first two are in the present indicative, and the third is a present participle. “There is…is called…having.” If words mean anything, what we are being told in this verse is that these words were first uttered at a time when the Sheep Gate and the pool, and its five porches were still just as they had been [since the time of Jesus]. Jerusalem was still standing, and the “desolation” which the Romans left behind in A.D. 70 had not yet taken place. We look again at the words, and they tell us something more. It is evident that the speaker is not only alluding to what still exists, but that he thinks that it is reasonably probable that his hearers are familiar with the sheep gate and will remember seeing the pool. He endeavors to recall it to their minds. “It has five porches,” he says: just as you or I, in speaking of a house in our own town, might say: “It is a tall house, in the High Street, just opposite the church; and it has a green door.” This scrap of information about the porches could only be given in speaking to people who knew Jerusalem at the time when the city was still standing; people who had often come through the sheep gate and would probably have noticed the pool with its graceful “porches” as they passed.21

Richard Lenski (1961)

Now there is in Jerusalem… “Is” = is still, after the destruction of Jerusalem, when John wrote; it is not the “is” of vivid narrative, since the narration goes on with ordinary tenses.22

John A.T. Robinson (1976)

This is one of John’s topographical details that have been strikingly confirmed in recent study. Not only does it reveal a close acquaintance with Jerusalem before 70, when the evidence of the five porches was to be buried beneath the rubble only recently to be revealed by the archaeologist’s spade; but John says not “was” but “is.” Too much weight must not be put on this—though it is the only present tense in the context, and elsewhere (Jn 4:6, 11:18, 18:1, 19:41) he assimilates his topographical descriptions to the tense of narrative…The natural inference, however, is that he is writing when the building he describes is still standing.23 Robinson concluded that all the books of the New Testament should be dated before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, and he ended up placing John sometime between 40 and 65 AD.24

[I]n John there is even less than in the Synoptics that can be taken as a reference to the fall of Jerusalem after the event. Indeed the presumption is that it is still standing as the evangelist himself describes it in the three present tenses of Jn 5:2 (though nothing can be built upon them): “There is in Jerusalem a place which is called in the language of the Jews Bethesda, having five porches.” The only forecast is that the Romans would come and destroy the city and its holy place if the Jewish authorities left Jesus at large (Jn 11:48) – in fact an unfulfilled prophecy, for they did not and the Romans still came.25

D.A. Carson (1991)

The words “there is in Jerusalem...a pool” have been taken by some as evidence that John wrote his Gospel before the siege and destruction of Jerusalem (AD 66–70). That is possible, but far from certain: John frequently uses the present tense to refer to past events (the so-called ‘historic present’).26

Leon Morris (1995)

If the present tense “is” is significant it points us to a time before the destruction of Jerusalem. This cannot be pressed, but neither should it be overlooked.27 This is found in Morris’ 1995 revised edition of his commentary on John in which he appears to have modified his view of the date of the Fourth Gospel. In his introductory comments, he sides with scholars who suggest that John may have been written as early as the 50s or 60s.28

Carsten Peter Thiede (1997)

Most people would say [the Fourth Gospel] dates to the late first century. Now, consider the archaeological facts we have these days. For example, in John 5:1 he describes the healing of the lame man at the Pool of Bethesda. John tells the story in the past tense. But then he tells readers where it happened as if saying: “If you want to see where Jesus did this miracle, then go to the Pool of Bethesda; it’s still there,” and he describes it. The pool was rediscovered-exactly the way he described it-earlier this century, but it had been destroyed in A.D. 70 by the Romans. So this account must have been written and was never changed before the year 70. No one after 70 could have written that there still is a pool in Jerusalem called Bethesda. So we have, for the Gospel of John, a historical, archaeological yardstick that indicates it was written before the year 70. And this is only one example of many. You could go on through the Gospels…[and] you would find argument after argument, pointer after pointer—archaeological, historical, literary, cultural, linguistic—for a date of all the Gospels and Acts before A.D. 70 and indeed much earlier.29

Craig Blomberg (2001)

An interesting grammatical observation that has convinced some of a pre-70 date is the use of the present tense in 5:2 — “Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool, which in Aramaic is called Bethesda, and which is surrounded by five covered colonnades.” After Jerusalem’s destruction, these statements would no longer be true; one would expect past-tense verbs. On the other hand, John frequently uses the historical present tense and that may be all he is doing here, to mark out the scene more vividly. Daniel Wallace responds that he can find no other use of the historical present with the verb “to be” (Gk. eimi), but it is difficult to know how much significance to attach to this observation.30

W. Hall Harris (2001)

A possible indication that Jerusalem was still undestroyed at the time the Fourth Gospel was written is found in Jn 5:2, which speaks of the pool of Bethesda (Bethzatha according to some manuscripts) with its five porticoes as still standing, using a present tense. The present tense is the only one in the immediate context—the writer uses imperfects for the rest of the description. This appears to give it special significance. Elsewhere in the Fourth Gospel (4:6, 11:18, 18:1, 19:41) John assimilates such topographical descriptions into the context. The natural inference from this use of the present tense is that John is writing while the building is still standing…Finally, the strong Palestinian influence throughout the gospel also suggests an early date. After John left for Ephesus and lived there for many years, such details would tend to fade and blur in memory. In conclusion, the Fourth Gospel was probably written shortly before AD 70 and the fall of Jerusalem.31

Craig S. Keener (2003)

Scholars today often credit John with topographic reliability in matters such as the one at hand [here in Jn 5:2]; external evidence confirms the existence of a pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem before the city’s destruction, even though it is usually held that John writes over two decades after that event…The pool is near the “sheep gate” (5:2), which, like the rest of old Jerusalem, was near the temple…”32

Andreas Köstenberger (2007)

[R]egarding the date of composition for John’s Gospel…only a very tiny minority of scholars argue for a pre-AD 70 date. I continue to be puzzled by Wallace’s strong interest in arguing for such a date. In my view (and also that of Craig Blomberg, D. A. Carson, and others), the tense form of a single Greek verb in John’s Gospel is hardly able to bear the heavy weight Wallace puts on it in proving the date of composition of the entire Gospel. Not that the majority is necessarily always right in biblical studies, but it must be said that there are good reasons why the virtual consensus of Johannine scholars holds to a post-AD 70 date.

Second, I continue to believe that we must be careful not to dismiss too quickly the possibility that a present-tense form of eimi may be used in biblical narrative within a temporal scope that includes the past…In any case, I do not expect that many students of John’s Gospel will believe that the date of John’s Gospel can be established by a disputed use of one single verb tense in the Gospel (of course, Wallace may dispute that this point is disputed, but I dispute this!)…For these reasons, I think it is unwise for anyone to champion the view that John was written prior to AD 70, whether on the basis of the present tense form of eimi in John 5:2 or otherwise.33

Thomas L. Stegall (2009)

In his article “Reconsidering the Date of John’s Gospel,”34 Stegall argues that John 5:2 presents a “significant piece of internal evidence” that lends support for an earlier dating of John’s Gospel. In fact he writes, “The prima facie reading of this verse indicates that the pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem and its five porticoes were intact at the time of John’s writing, thus providing a solid piece of evidence from within John’s Gospel that he wrote before the razing of the Jerusalem Temple in a.d. 70.”

William C. Weinrich (2015 )

The observation of Thyen is convincing: “According to its inner logic, the function of Jn 5:2 is to locate the less well-known [Bethesda] by referring to the generally well-known [Sheep Gate].” The Sheep Gate was destroyed by Titus in AD 70. This is implied by the report of Josephus:

Caesar gave orders that they should now demolish the entire city and temple, but should leave as many of the towers standing as were of the greatest eminency; that is, Phasaelus, Hippicus, and Mariamne, and so much of the wall as enclosed the city on the west side…but the rest of the wall was so thoroughly laid even with the ground by those that dug it up to the foundation, that there was left nothing to make those that came thither believe it had ever been inhabited (War, 7:1,3).

Assuming a post-70 dating of the Gospel, Schlatter writes that “there must have been a renovation of the earlier gate.”35 In the introduction to his commentary, Weinrich lists several reasons why he believes the Fourth Gospel should be dated before the fall of Jerusalem and concludes with a proposal that it was “composed in Jerusalem during the 40s and [was] taken with John to Asia Minor in the early 50s.36

J. Warner Wallace (2017)

In chapter 5, verse 2, John wrote, “there is in Jerusalem, by the sheep-gate, a pool (the one called Bethesda in Hebrew) which has five porticoes.” John used the present tense word “is” (ἐστιν) when describing the existence of the pool, yet the pool was destroyed in 70AD when Jerusalem was sacked by the Romans…John appears to have written this passage very early (as someone who knew Jerusalem intimately) to people who were familiar with the pool…In addition, the Muratorian Fragment, containing information dated to approximately 180AD, describes the origin of John’s Gospel and seems to take for granted the fact that John’s “fellow-disciples” (including the apostle Andrew) were still alive and present with John when he wrote his account. This would also argue for an early date of authorship…John’s Gospel most reasonably appears to have been written after the other Gospels and prior to 70AD.37

James H. Charlesworth (2019)

The author informs us that there is a large pool in Jerusalem…near a place defined by sheep. If it denotes a sheep pool, it cannot be a place for washing sheep. The excavated pools are far too deep for washing a sheep…This area, north of the Temple, was mentioned by Nehemiah: “Then Eliashib the high priest arose with his brothers the priests and built the Sheep Gate…” (Neh 3:1; cf. 3:32, 12:39).

For 2,000 years, New Testament scholars have searched for spiritual nourishment by claiming to perceive a brilliant Christological creation in John 5; that is, the realization and affirmation that Jesus is the Great Healer, the Savior. Their focus on Christology led to a failure to perceive that the Evangelist may be describing, quite accurately an architectural feature of pre-70 Jerusalem.38

John is not a late composition…the form in which most Christians know John is with 7:53 - 8:11; but this passage about the woman caught in the act of adultery was not part of the first edition...I am convinced that the earliest edition of John—the first edition—may antedate 70 CE. Why? It is because the author knew Jerusalem intimately, providing many architectural details which only thirty years ago we imagined were literary inventions…”39

John has amazing details about pre-70 CE Jerusalem and archaeologists are frequently able to prove John’s historical accuracy.40 The Pool of Bethsaida (Bethzatha) does have five porticoes and the columns can be seen today lying on the ground.41 All the reasons that require a late date for the Gospel of John (sometime after 90 CE) have vanished. There is no longer a consensus regarding the date of John.42

Items from the past do not come already interpreted. Archaeologists disagree, sometimes markedly, on the date and importance of an item. Our best method for assessing the date of John is the extant text of John.43 The composition of John makes best sense if the definitive form, the first edition, was composed before 70 CE.44 There is no reason to contend that it must have been composed after 70 CE.45

While many scholars during the twentieth century agreed that John is late, dependent on the Synoptics, and took shape in the last decade of the first century CE, a consensus has appeared that each of these points is either inaccurate or in need of reconsideration.46 Is it possible, then, to observe a paradigm shift…? Yes.47

Lydia McGrew (2021)

There is a small contingent of scholars who argue for a very early date [of the Fourth Gospel], prior even to the fall of Jerusalem in 70. One of the major arguments they focus on is the use of the present-tense verb in John 5.2, where the author says that there is a pool named Bethesda by the Sheep Gate. This is taken to point to a date before Jerusalem (and the Pool of Bethesda) were destroyed in 70. While I am not closed to the idea of a pre-70 date, this interesting verbal indication seems to me insufficient for a strong conclusion to that effect.48

Jonathan Bernier (2022)

[John A.T.] Robinson addresses this passage but does not give it the full weight that it deserves. John 5:2 informs the reader that “in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate there is a pool, called in Hebrew Beth-zatha [Bethesda], which has five porticoes. The present tense is not simply an artifact of translation into English but is native to the Greek text. The relevant verbs are estin, the third-person present active indicative of the verb eimi (to be); and echousa, a present active participle of echo (to have). The most natural reading of the present tense in this passage is that this pool existed when the author was writing. Since the pool was destroyed in 70, we should prefer pre-70 composition for Jn 5:2.49

Although Robinson recognizes that this passage is most fully intelligible prior to 70, he does not fully appreciate the extent to which this is true. In fairness to Robinson, he did not have access to Daniel Wallace’s now-classic study on the matter, which appeared more than a decade after Redating the New Testament…[in which he challenged the view that] in John 5:2 eimi constitutes a historic present, such as we find when Josephus refers to the temple while using the present tense decades after the temple’s destruction. Wallace argues, however, that linguistically speaking, the historical present typically is associated with action verbs, not with verbs of being….Moreover, Wallace observes that he could not find a single instance of eimi being used as a historical present within the New Testament. In response to Wallace, Craig Blomberg writes, “It is difficult to know how much significance to attach to this observation. After all, most historical presents occur in a narrative where a specific verb of speech or action is highlighted.” Blomberg’s observation, however, seems to strengthen rather than weaken Wallace’s argument that historical presents are not typical of verbs of being, but rather of verbs of action. Considering the above, a historical present is unlikely. As such, it is probable that John 5:2 means to reference conditions as they stood at the time of composition.50

N.T. Wright (2022)

On episode 144 of his podcast, Wright said, “The current Lady Margaret professor of New Testament in Cambridge, George van Kooten, is arguing in his new book on John for a much earlier date, a date I think maybe even in the 40s, or certainly the 50s. And I would say, actually, you don’t have to wait a long time to get deep theological reflection. The highest Christology in the New Testament is probably Philippians 2:6-11, which may well be a poem that’s already written before Philippians, in other words, in the late 40s or early 50s. So theological development doesn’t take place on a slow chronological line, it takes place in leaps and bounds and it’s quite possible that the traditional dating of the Gospels in scholarship, which has a late John, may well be wrong.”51 Professor van Kooten’s argument for redating John is rooted in John 5:2, and his book is slated to be published in late 2024.

John Dickson (2024)

On episode 126 of his podcast, Dickson recently stated that “Most scholars date John to about the 90s AD. That’s what I’ve taught for years…but the work of a few outlier scholars in recent times has left me thinking nowadays that this Gospel could be as early as Mark’s Gospel—so, the 60s AD.”52 Though he didn’t identify the names of those outlier scholars or the specific facts that ended up changing his thinking, his comments certainly reflect a new openness concerning the date of the Fourth Gospel.

George van Kooten (2024)

In August of 2024, Cambridge Professor Van Kooten argued in a public lecture53 that John may be the earliest of the Four Gospels. The lecture was titled, ‘An Archimedean point for dating the Gospels: the pre-70 CE date of John, the special Lukan-Johannine relationship, the posteriority of Luke, and the non-necessity of Q.’ Here is the way Dr. van Kooten summarized his address:

An Archimedean point for the solution of [the date of the Fourth Gospel] is now proposed in the present tense that John uses to tell that ‘there is in’ (ἔστιν δὲ ἐν) Jerusalem a monumental Herodian pool- with-five-porticoes (5:2), which was probably destroyed during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 CE). This argument has been proposed before by Bengel (1742), Blass (1907), Robinson (1976/85), and Wallace (1990) but is now for the first time based on broader grammatical, historical, and archaeological observations…If the Gospel of John is to be dated before 66 CE, it seems likely that John is prior to Luke and that it was Luke who was using John…Luke mainly employs John in his narrative of the trial, death, and post-resurrection appearances of Jesus and it seems that he, as in a Διὰ τριῶν, makes use of all three Gospels before him, including John’s.

You can find van Kooten’s lecture handout here, and a summary of his presentation by Ian Paul here. In an interview recorded before he gave this lecture,54 van Kooten pointed out that John 5:2 follows an existing formula in its description of the pool of Bethesda, which indicates that it was still in existence at the time of writing. “The expression ‘there is…’,” he argued, “is only used for that purpose. Historians date Greek texts on the basis of this formula.”

Richard Bauckham (2024)

“I saw no reason not to accept the late date [of John] until George [van Kooten] produced his argument about Jn 5:2…In Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, I accepted the most common dating of the Gospels…So George’s argument about Jn 5:2 has disturbed me!” Concerning the date of the Synoptics, Bauckham writes, “Nowadays I am toying with a date for Mark in the 40s and Luke and Matthew (in that order) before 66.”55

Peter J. Williams (2024)

On a recent interview on The Humble Skeptic podcast (episode #62), Williams says: “The professor in Cambridge, George van Kooten is arguing for a pre-70 date for the Gospel of John. Also, on those same grounds, I think there’s no reason why it has to be later…Because it says in John chapter 5 ‘there is in Jerusalem this gate, that makes more sense before the year 70.” Williams, however, was quick to add that though this exegetical argument based on John 5:2 seems to make more sense, “it doesn’t absolutely force my hand…For me, the question is not so much about the date of the Gospel as who’s it from…whenever the Gospels date from, they are all from people who are either eyewitnesses, in the case of Matthew and John or are close to eyewitnesses…” In his 2018 book, Can We Trust the Gospels, Williams similarly argued that “the four Gospels are so influenced by Judaism in their outlook, subject matter, and detail that it would be reasonable to date them considerably before the Jewish War.”56

Michael J. Gorman (2024)

In September 2024, Dr. Gorman gave a series of lectures in which he argued that John and Paul share numerous thematic and linguistic features that are best explained if Paul had been influenced by the text of the Fourth Gospel. He therefore suggests that John was likely written “before the year 50 AD.” Gorman also cited the recent work of George van Kooten, and Jonathan Bernier as providing compelling evidence for a pre-66 dating of John’s Gospel, noting that both scholars highlighted the importance of John 5:2.57

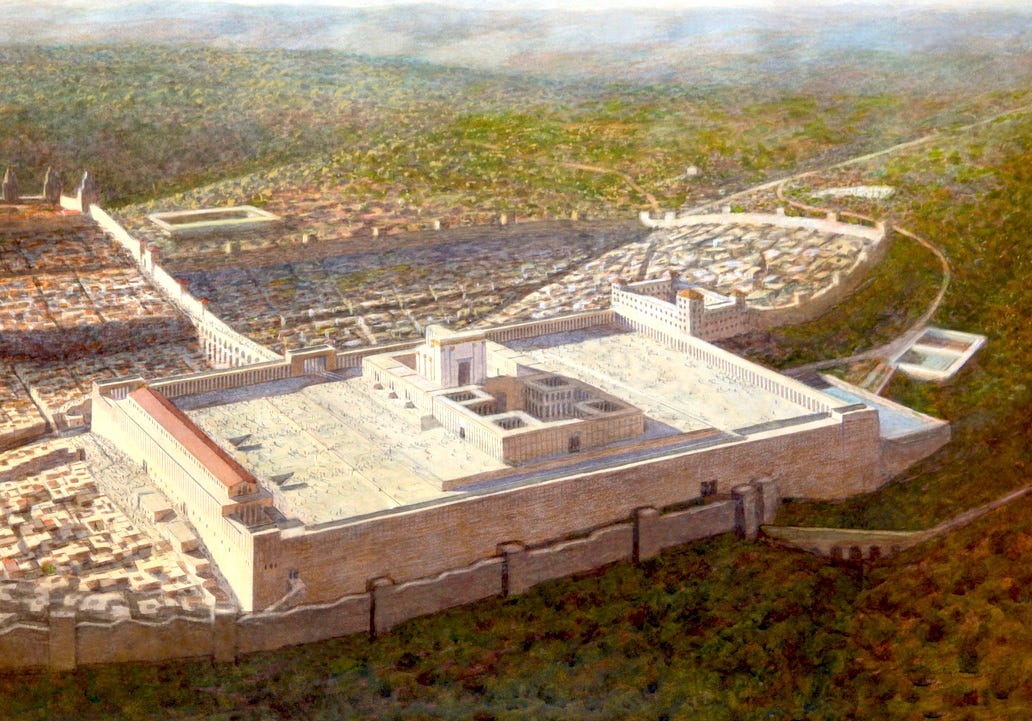

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast, which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and has written numerous articles for TableTalk, Core Christianity, Modern Reformation, and numerous other sites and publications. Shane received a B.A. in Humanities from Cal-State Fullerton and an M.A. in Historical Theology from Westminster Seminary California. The illustration of Jerusalem presented at the beginning of this post was created by Balage Balogh from Archaeology Illustrated, and is used by permission.

For additional resources related to this topic, click here.

If you are unfamiliar with the grammatical concept of a “historical present,” I strongly encourage you to listen to episode 51. This page also includes numerous books and resources for further reading on the issue of the dating of the Fourth Gospel.

Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 531.

Daniel B. Wallace, John 5:2 and the Date of the Fourth Gospel...again

Daniel Whitby, A Paraphrase and Commentary on the New Testament, Vol 1 (London: W. Bower et al, 1709), 468.

“Bishop Atterbury’s Epistolary Correspondence, Etc.”, The Monthly Review, Vol 71 (London: R. Griffiths, 1785), 47-48. This was printed in July, 1784, but the original letter was likely written sometime around 1710.

William Whiston, An Essay on the Apostolic Constitutions (London: Printed for the Author, 1712), 19.

W.L. Blackley and James Hawes (editors), The Critical English Testament, Vol 1 (London: Daldy, Isbister & Co., 1876), 573-574. I believe this quote originally appeared in Bengel’s Exegetical Annotations on the New Testament, which was first published in 1742.

John Wesley’s Notes on the Whole Bible (commentary on John 5:2). His Explanatory Notes on the New Testament was first published in 1755.

Nathaniel Lardner, A History of the Apostles & The Evangelists, Writers of the New Testament (London: J. Buckland et al, 1760), 416-418. The first edition was published in 1756.

Henry Owen, Observations on the Four Gospels (London: T. Payne, 1764), 104. This writer dates the Fourth Gospel to the year 69 AD.

John David Michaelis, Introduction to the New Testament (London: F.C. & J. Rivington, 1823), 322-323. According to the translator’s preface, the fourth edition of this work was first translated into English in 1795 (meaning the original was written some time before this—and significantly earlier if these statements can be found in earlier editions).

Charles Taylor and Edward Robinson (editors), Calmet’s Dictionary of the Holy Bible (Boston: Croker & Brewster, 1832), 166.

Samuel T. Bloomfield, The Greek Testament with English Notes, Vol. 1 (Boston: Perkins & Marvin, 1836), 329.

John Peter Lange, Lange’s Commentary on the Holy Scriptures: John (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1871), 180

F. Godet, Commentary on the Gospel of John (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1886), 455. The first edition of this book was published in 1879.

B.F. Westcott, The Gospel According to St. John (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981 reprint; 1881), 81

J.B. Lightfoot, The Gospel of St. John: A Newly Discovered Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015), 143

Ibid., 197

Friedrich Blass, “The Origin and Character of our Gospels, III: St John,” Expository Times 18.10 (July 1907) 458–459.

This city (pronounced “eeprah”) is roughly 80 miles west of Brussels in Belgium.

Hubert Edwin Edwards, The Disciple Who Wrote These Things: A new inquiry into the origins and historical value of the Gospel according to St. John (London: James Clarke & Co, 1953), 126-127

R.C.H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. John’s Gospel 1-10 (St. Louis: Augsburg, 1961), 361

John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 278

Ibid., 352

John A.T. Robinson, The Priority of John (London: SCM Press, 1985), 70

D.A. Carson, The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 241

Leon Morris, The Gospel According to John, Revised - NICNT (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1995), 265

Ibid., 25-30

An interview with Carsten Peter Thiede, conducted by John Ross Schroeder, Good News Magazine, Dec 1, 1997.

Craig L. Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2001), 43.

W. Hall Harris, The Gospel of John: Introduction and Commentary (Biblical Studies Press, 2001), 18. https://bible.org/seriespage/background-study-john

Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary Vol 1. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 636.

Andreas Köstenberger, “Was John’s Gospel Written Prior to AD 70?” Wallace responded to Köstenberger by writing, “John 5.2 One More Time: A Response to Andreas Köstenberger.”

Thomas, L. Stegall, “Reconsidering the Date of John’s Gospel,” Chafer Theological Seminary Journal, Volume 14, Number 2 (Fall, 2009).

William C. Weinrich, John 1:1-7:1 (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2015), 551, n. 12

Ibid., 44-51

J. Warner Wallace, “John’s Gospel May Have Been Last, But It Wasn’t Late,” published online at Cold-Case Christianity, March 13, 2017.

James H. Charlesworth, Jesus as Mirrored in John (London: T&T Clarke, 2019), 190.

Ibid., 2

Ibid., 155

Ibid., 153

Ibid., 47

Ibid., 48

Ibid., 47

Ibid., 49

Ibid., 41

Ibid., 155

Lydia McGrew, The Eye of the Beholder (Tampa: DeWard Publishing Co., 2021), 148

Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking The Dates of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2022), 97. Though he disagrees with Robinson’s approach at various points, Bernier ends up agreeing with his overall premise that the entire New Testament was written before 70 AD. In his 2018 book, Can We Trust The Gospels?, Peter J. Williams similarly argued that all four Gospels “are so influenced by Judaism in their outlook, subject matter, and detail that it would be reasonable to date them considerably before the Jewish War” (p. 81).

Ibid., 98-100

Undeceptions, Episode 126, “Jesus’ Biography,” May 6th, 2024 (this quote appears approx. 12 minutes into the episode.

British New Testament Society Conference, Aug. 22–24, 2024 at The University of Glasgow. For George van Kooten’s address, see page 15 of this PDF.

Recorded on March 31, 2024. You can find an English translation of selections from this interview here.

You can find these recent statements by Bauckham in the comments section of an online article by Ian Paul titled, “Was John the First Gospel?” Bauckham’s comments were posted in Aug. and Sept. of 2024, however, I have not presented them in chronological order.

Peter J. Williams, Can We Trust the Gospels? (Wheaton, Crossway, 2018), 81.

The Historic Present is Common in Ancient Literature

Many scholars arguing for a pre-70 CE date assume that because John 5:2 states “there is (ἔστιν) in Jerusalem a pool,” this must mean that the pool was still standing when the Gospel was written.

However, as seen in Homer’s descriptions of Troy, Herodotus' descriptions of Babylon, and Josephus’ own present-tense references to the Jerusalem Temple even after its destruction, ancient writers frequently used the present tense when describing places that were long gone.

In The Jewish War (7.1.1), Josephus describes the Jerusalem Temple in the present tense, despite it having been destroyed.

Regarding the verb "εἰμί" (to be), which includes forms like "ἐστίν" (estin), Josephus's usage varies. In many descriptions, he employs past tenses, but there are instances where he uses the present tense, possibly for emphasis or stylistic reasons. For example, in Book 5, Section 193, he describes a stone partition:

"διὰ τούτου προϊόντων ἐπὶ τὸ δεύτερον ἱερὸν δρύφακτος περιβέβλητο λίθινος..."

Translated: "When one proceeds through the cloisters to the second court of the temple, there is a stone partition..."

In this context, "περιβέβλητο" (peribeblēto) is a past perfect form, indicating a completed action in the past. Yet, the act of proceeding ("προϊόντων") is presented in a present participle form, suggesting an ongoing action.

Herodotus, in Histories (5th century BCE), describes Babylon and its famous walls, despite the city already being in decline.

If John’s Gospel were written after 70 CE, it would not be unusual for the author to describe a destroyed landmark in the present tense.

Mark: Mark frequently uses the historical present to describe past events, a feature that is well-documented in New Testament scholarship. This stylistic choice gives the narrative a sense of immediacy and vividness, making the reader feel as if the events are unfolding in real time.

Mark’s Use of the Historical Present

The historical present is a grammatical feature in which a present-tense verb is used to describe a past event. It is particularly common in narrative literature to create a dramatic and engaging effect.

Example in Mark 1:40-41 (literal Greek)

Καὶ ἔρχεται πρὸς αὐτὸν λεπρὸς… καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ… καὶ σπλαγχνισθεὶς ἐκτείνας τὴν χεῖρα αὐτοῦ ἥψατο αὐτοῦ καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ…

Translation: “And a leper comes to him… and says to him… and being moved with compassion, stretching out his hand, he touches him and says to him…”

Although this describes a past event, Mark uses έρχεται (comes) and λέγει (says) in the present tense instead of the expected aorist (past) tense.

Other examples in Mark

Mark 2:5 – λέγει τῷ παραλυτικῷ (“he says to the paralytic”) instead of “he said.”

Mark 4:37-39 – A sequence where Jesus rebukes the wind and the storm in the present tense.

Mark 5:15 – The Gerasene demoniac is described in the present tense.

How Does This Relate to John 5:2?

The debate over John 5:2 hinges on whether ἐστιν ("there is") is a historical present or an actual present referring to a still-existing structure. If John used the historical present like Mark, then ἐστιν might not indicate that the pool of Bethesda was still standing at the time of writing.

However, scholars like Daniel Wallace argue that εἰμί (the verb “to be”) is almost never used as a historical present in Greek, including in the New Testament. This is unlike verbs of action (e.g., “he says,” “he comes,” “he does”), which appear in the historical present frequently.

Thus, while Mark provides clear examples of the historical present being used to describe past events, the challenge is whether John 5:2 can be similarly interpreted. The uniqueness of εἰμί in historical narrative makes it a contested case.

2. Archaeological Evidence Does Not Require a Pre-70 Date

The claim that John’s architectural descriptions suggest an eyewitness account before 70 CE ignores that many ancient cities retained their recognizable ruins for centuries.

The Pool of Bethesda has been excavated and shown to have been a real structure, but ruins could still be visible in the late first or even second century CE.

The Romans often destroyed key structures but left partial ruins standing, as seen with the Sheep Gate itself, which is believed to have remained partially intact and destcribed by Christians visiting Jerusalem in the 5th century. Another layer of complexity lies in the fact that john never calls it a “gate” at all. The original text of John literally says “next to the sheepish” (ἐπὶ τῇ προβατικῇ) – in the literal sense of “something pertaining to the sheep.” This could be the “Sheep Market,” the “Sheep Pasture” or even the “Sheep Pool.”

3. Later Writers Also Used the Present Tense to Describe Destroyed Sites

If we followed the logic that a present-tense verb proves a structure still existed at the time of writing, then we would have to assume that all ancient descriptions of vanished cities were contemporaneous with those cities' existence.

This is demonstrably false:

Strabo (1st century BCE - 1st century CE) describes Nineveh as if it were still present, long after its destruction in 612 BCE.

Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) describes Carthage, despite its destruction in 146 BCE.

Pausanias (2nd century CE) describes the ruins of Mycenae in vivid present-tense descriptions, despite the city’s collapse long before his time.

John could simply be using the same stylistic convention to describe the Jerusalem of memory.

4. A Counterexample: The Sack of Troy

Homer’s Iliad (8th century BCE) describes the city of Troy as if it were a contemporary setting, yet Troy (if it corresponds to Hisarlik) was destroyed around the 12th century BCE.

Later writers like Strabo and Pausanias continued to describe Troy in the present tense despite its ruins being all that remained.

If we were to use the same logic applied to John 5:2, we would have to date the Iliad to the 12th century BCE, which we know is false.

The mere use of present tense does not establish contemporaneity.

5. Selective Application of Evidence

Scholars arguing for an early date based on John 5:2 often ignore similar present-tense descriptions elsewhere in ancient literature.

They also selectively apply evidence from patristic writers. The same scholars who take Irenaeus’ testimony that John was written by the apostle often ignore his claim that Jesus was about 50 years old when he was crucified (Against Heresies 2.22.5).

Similarly, early Christian writers often accepted that Matthew was written in Hebrew (a claim many scholars today reject) while still maintaining that John was written last.

If scholars reject patristic claims about other Gospels, why should they privilege the tradition about John’s date?

6. Conclusion: The Present-Tense Argument is Circular

The argument that John 5:2 necessitates a pre-70 CE date is circular:

Premise: John 5:2 uses the present tense.

Assumption: The present tense must mean the structure was still standing.

Conclusion: Therefore, John must have been written before 70 CE.

This logic ignores abundant ancient examples of places and structures being described in the present tense long after their destruction.

In short, the present-tense argument for John’s early dating is weak and contradicts well-known ancient literary practices. The example of Troy, among others, demonstrates that ancient authors frequently described destroyed cities and structures as if they were still standing. If we were to apply the same reasoning consistently, we would have to radically revise our dating of many ancient texts. Even if John was written 50 years after the destruction of Jerusalem, the memory of the city's architecture would have been passed on through at least the first generation. Not only that, but there would still have been people alive who remembered the temple, it's layout and the larger layout of Jerusalem.