Who is Sergius Paulus?

He was an obscure ruler mentioned by Luke in Acts 13 whose existence has been corroborated through a variety of ancient inscriptions and textual sources.

In his book, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament, Oxford historian A.N. Sherwin-White famously observed that, “For Acts the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming…[and] any attempt to reject its basic historicity even in matters of detail must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted.”1 Similarly, in his discussion of the book of Acts in The Oxford Companion to the Bible, F.F. Bruce noted that,

Luke is the only New Testament writer who so much as names a Roman emperor; in addition to emperors, he introduces provincial governors, client kings, civic magistrates, and other local officials. Scholars have drawn attention to the accuracy with which these officials are designated by their correct titles—and accuracy the more noteworthy because some of those titles changed from time to time. Provinces under the nominal control of the Roman senate, for example, are governed by proconsuls, like Sergius Paulus in Cyprus and Gallio in Achaia; Philippi has praetors or duumvirs as its chief magistrates, because it is a Roman colony; Thessalonica is administered by politarchs, a title attested on a number of inscriptions as borne by the chief magistrates of Macedonian cities. The record of Acts is interrelated with contemporary world history in a way that entitles it to be cited as an authority in its own right.2

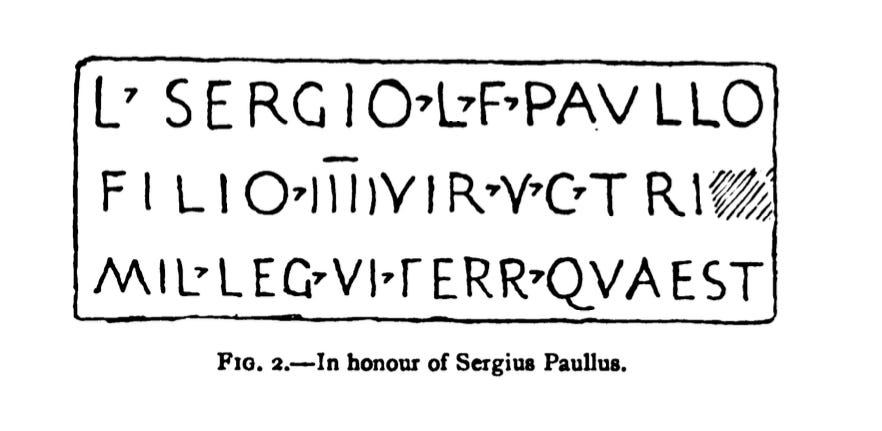

I recently posted a condensed version of Sir William Ramsay’s own account of how he came to regard the book of Acts as an authentic first-century document. In the unabridged version of his book, Ramsay also went on to discuss the discovery of an inscription that served to corroborate events recorded by Luke in Acts 13:6-9. This is the scene in which Paul and Barnabas arrive in Paphos on the island of Cyprus, and happened to meet a proconsul by the name of Sergius Paulus. According to Ramsay, subsequent references to this local ruler “seemed almost to have perished…until 1912 when we began the systematic excavation of Pisidian Antioch.” But during that year, his team discovered an inscription that featured the name of “Lucius Sergius Paullus the younger,” which Ramsay “at once confidently recognized as the son of the Proconsul of Cyprus.”3

Colin Hemer was a little skeptical of this particular linkage by Ramsay. “The name of the proconsul cannot be confirmed,” he wrote, “but the family of the Sergii Pauli is attested…”4 “It is possible,” he went on to say, “that the Lucius Sergius Paullus mentioned as one of five curators [of the Tiber river] under Claudius was the same man…but there is nothing to corroborate this possibility beyond the coincidence of name and time, and nothing to connect this man with Cyprus…”5

F.F. Bruce offered a few suggestions of his own. The proconsul mentioned by Luke in Acts 13:7 could possibly be “Quintus Sergius Paullus [who is] mentioned in an inscription from Kythraia, north Cyprus, as holding office in the island apparently under Claudius.” Additionally, he says, “An inscription of Soloi, north Cyprus, mentions a proconsul named Paullus who held office in some emperor’s tenth year. If the emperor were Claudius, the date (AD 50/51) would be too late for the Sergius Paullus of Acts…”6

Whether or not we can correctly identify the specific ruler mentioned in Acts 13:7 among all the competing options, Ben Witherington persuasively argues that,

[T]he inscriptional evidence clearly places the Sergii Pauli on the island of Cyprus, and the Latin inscriptions about Lucius of that family may point us to the man in question…The fact that the Latin inscriptions are datable to the 40s, like the text of Acts 13, and mention a prominent Sergius Paulus as a public official, suggests a connection between the two since Paul’s visit to Cyprus must also be dated to the reign of Claudius in the later 40s. This would provide one more piece of evidence, though indirect, that Luke is dealing with historical data and situations, not just creating a narrative with historic verisimilitude.

J.B. Lightfoot (1828-1889), in his recently discovered commentary on Acts, proposed another tantalizing connection. “In the index of contents and authorities that forms the first book of Pliny’s Natural History this writer twice names one Sergius Paulus among the Latin authors to whom he is indebted. May not this have been the same person?”7 Pliny lived from 24-79 AD, which means he was alive around the same time as the ruler cited by Luke in Acts 13:7. Lightfoot then went on to say,

The Sergius Paulus of Pliny is named as an authority for the second and eighteenth books of that writer…We therefore look with interest to see whether these two books of Pliny contain any notices respecting Cyprus…and our curiosity is not disappointed. In the second book…Pliny [describes] an area in the temple of Venus at Paphos…[and] in the eighteenth book again, besides an incidental mention of this island he gives some curious information with respect to the Cyprian corn, and the bread made therefrom.8

What I find particularly striking is the fact that, according to Luke, the proconsul of Cyprus had with him “a certain magician, a Jewish false prophet named Bar-Jesus” (Acts 13:6). In another section of his Natural History, Pliny indicates that this sort of thing was not at all uncommon in the ancient world. For example, he says that a magician named Osthanes “traveled…all over the world” with Alexander the Great,9 and a Magus by the name of Tiridates accompanied Nero, but that unfortunately, the emperor was “unable to acquire from him the magic art.”10 And interestingly enough, Pliny also points out two other interesting facts: 1) Jewish magicians really did exist in this period, and 2), there also happened to be a group of magicians who resided on the island of Cyprus. Here’s what he writes: “There is yet another branch of magic, derived from Moses…and the Jews…So much more recent is the branch in Cyprus.”11

Exploring details of this kind led Lydia McGrew to argue in her book, Hidden in Plain Sight: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels & Acts, that “The book of Acts is a gold mine of evidence for the truth of Christianity that is not always fully appreciated.” In fact, she went on to say:

The external evidence that supports its historical reliability is particularly striking…Acts is the only first-century source we have that claims to include speeches given by the apostles themselves during the very first days of the founding of Christianity…If these are accurate records of the substance of what was said, they show that the apostles testified from the beginning to Jesus’ physical resurrection and claimed to be eyewitnesses to this fact.12

In light of her research and all the minute details from the book of Acts that she was able to corroborate from a variety of sources, Dr. McGrew concludes her book by confidently asserting, “the idea that [the author of Acts] was writing in any sense a work of fiction can be readily dismissed.”13 And, as it turns out, this has huge ramifications for our understanding of Jesus as he is presented to us in the Gospels. As Dr. McGrew explained on a recent episode of The Humble Skeptic podcast,

The book of Acts was written by the same author as the Gospel of Luke, and therefore, the question becomes rather urgent, ‘What kind of person was Luke, what kind of author was he?’ I think there’s a tendency not to think strongly enough about authors as personalities—you know, who was this person, and what was he like? And that’s something that’s been a big emphasis in my own work, to learn about the character of the author from his work. And I think once we appreciate that concerning Acts, it casts a lot of positive light on the Gospel of Luke. So, for example, when we read the resurrection account in Luke 24, should we think he was the kind of author to embellish or change [things]…or is he the kind of author to have carefully consulted eyewitness sources and to have asked them questions, and written down faithfully what they told him in a very conscientious historical manner. And so, that’s why all this is so important. Acts is a clue to all these things.14

So what is the picture we get from a careful study of all the details recorded throughout the book of Acts? The resulting picture is precisely the one presented to us by archaeologist William Ramsay after a lifetime of research and investigation: “Luke [is] not merely trustworthy, but a historian of the highest order.”15 This author should be placed along with the very greatest of historians.”16

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of a national radio broadcast called the White Horse Inn, which he also hosted from 2019-2021. Shane has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Core Christianity, Modern Reformation, Heidelblog, and others. Shane received an M.A. in Historical Theology from Westminster Seminary California, and he lives with his family in the greater St. Louis area.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Is Luke a Trustworthy Historian?, by William M. Ramsay

Can We Trust Luke’s History of the Early Jesus Movement?, Shane Rosenthal

On Faith & History, Shane Rosenthal

Authenticating the Fourth Gospel, by Shane Rosenthal

Why Should We Believe the Bible?, by Shane Rosenthal

How to Detect Deception, by Shane Rosenthal

Authenticating the Book of Acts, featuring Lydia McGrew

What Did The Earliest Christians Believe?, featuring Dennis Johnson

A.N. Sherwin-White, Roman Society & Roman Law in the New Testament (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1963), p. 189

Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan (editors), The Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press: New York, 1993), p. 9. For a related discussion pertaining to the Gallio inscription, click here.

William M. Ramsay, The Bearing of Recent Discovery Concerning the Trustworthiness of the New Testament (Hodder & Stoughton: London, 1915), p. 150-151

Colin Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake, IN, 1990), p. 109

Ibid., p. 166, f15

F.F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles (Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, 1990), p. 297

J.B. Lightfoot, The Acts of the Apostles: A Newly Discovered Commentary (IVP Academic: Downers Grove, IL, 2014), p330. Pliny’s Natural History was written sometime around 77 AD.

Ibid., p. 331

Pliny, Natural History, Vol. 8 of the Loeb Classical Library edition (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1963), p. 285

Ibid., p. 289

Ibid., p. 285. In an earlier version of this article, I argued that Pliny’s quote implied that the magicians in Cyprus were of Jewish descent, which seemed to fit nicely with Luke’s report about the Jewish magician, Bar-Jesus. But after further study and reflection, I ended up concluding that this suggestion was too speculative. The Cyprus magicians could be seen as a sub-branch of the Jewish school since he mentions them almost in the same breath, but it could equally refer to a completely different non-Jewish branch.

Lydia McGrew, Hidden in Plain View (DeWard Publishing: Chillicothe, OH, 2017), p. 133-134

Ibid., p. 226

Episode 24: Authenticating the Book of Acts. Dr. McGrew makes these comments during the first 5 minutes of this episode.

William M. Ramsay, St. Paul The Traveller and The Roman Citizen (Hodder & Stoughton: London 1920) page v.

William M. Ramsay, The Bearing of Recent Discovery, p. 222