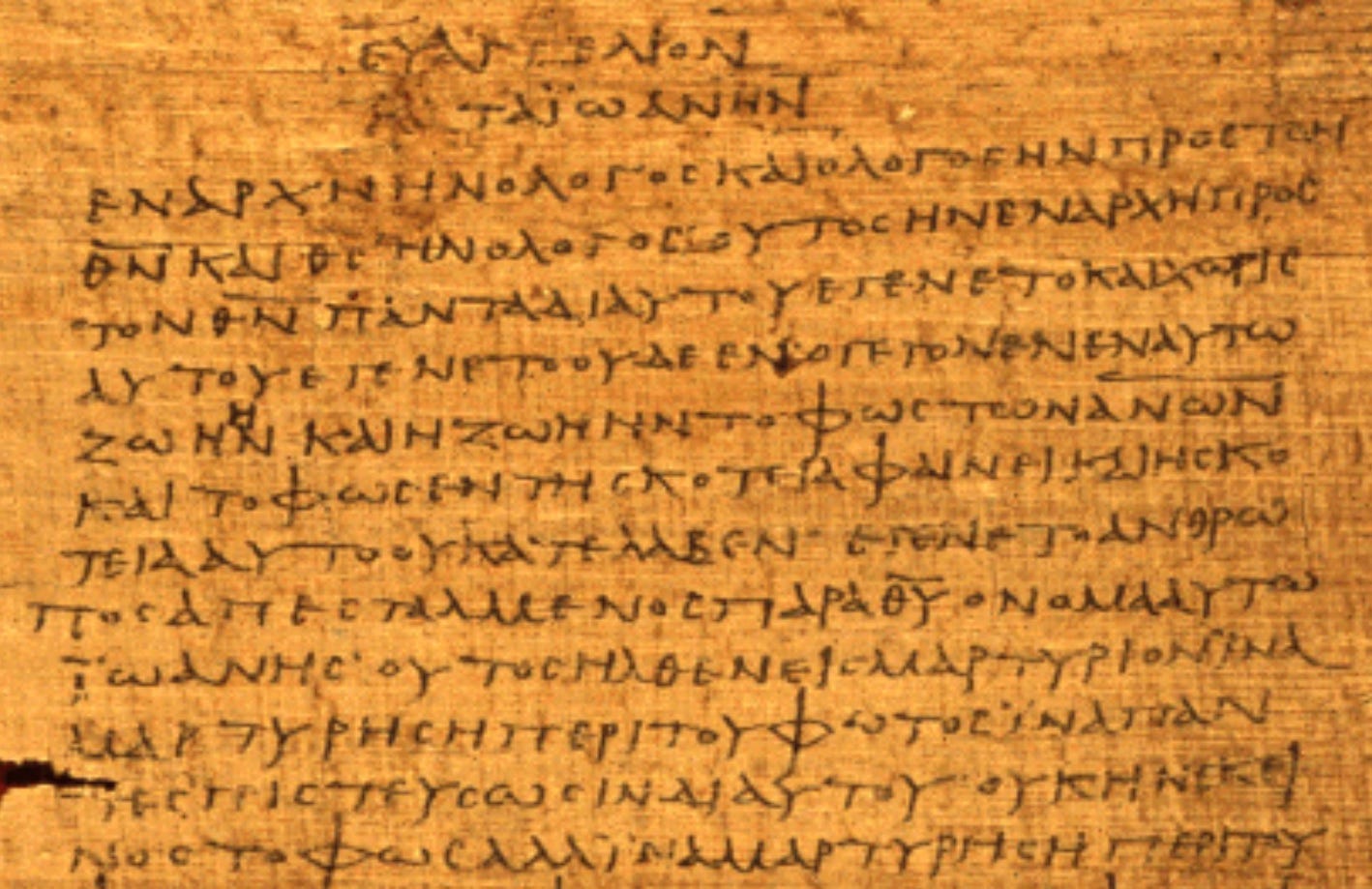

Internal Evidence for the Authenticity & Genuineness of the Fourth Gospel

by J.B. Lightfoot (1871)

Joseph Barber Lightfoot was an Anglican theologian and New Testament scholar of the nineteenth century. Born in Liverpool, he studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he eventually became Professor of Divinity. He edited a scholarly journal, authored numerous books, and served as chaplain to Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. The following piece is an abridged version of a chapter that appeared in his book, Biblical Essays (1893).

This essay originally formed a series of lectures connected with Christian evidences delivered in St. George’s Hall in 1871. Additional study since that time has only strengthened my conviction that this narrative of St. John could not have been written by anyone but an eyewitness.1 As I proceed, I hope to make it clear that, allowing their full weight to the difficulties (and it would be foolish to deny the existence of difficulties) in this Gospel, still the internal marks of authenticity and genuineness are so minute, so varied, so circumstantial, and so unsuspicious, as to create an overwhelming body of evidence in its favor.2

The contents of this Gospel present great difficulties for those who hold the hypothesis of a late date. In the interval between the age when the events are recorded to have taken place and the age in which the writer is supposed to have lived, a vast change had come over the civilized world. In no period had the dislocation of Jewish history been so complete. Two successive hurricanes had swept over the land and nation. The devastation of Titus had been succeeded by the devastation of Hadrian. What the locust of the first siege had left the cankerworm of the second had devoured. National polity, religious worship, social institutions—all were gone. The city had been razed, the land laid desolate, the law and the ordinances proscribed, the people swept into captivity or scattered over the face of the earth. ‘Old things had passed away; all things had become new.’

Now let us place ourselves in the position of one who wrote about the middle of the second century, after the later Roman invasion had swept off the scanty gleanings of the past which had been spared from the earlier. Let us ask how a fiction writer so situated is to make himself acquainted with the incidents, the localities, the buildings, the institutions, the modes of thought and feeling, that belonged to the people of this bygone era. Let it be granted that here and there he might stumble upon a historical fact and that in one or two particulars he might reproduce a national characteristic. More than this, however, would be beyond his reach.

For, it will be borne in mind, he would be placed at a great disadvantage, compared with a modern writer; he would have to reconstruct history without those various appliances, maps and plates, chronological tables, and books of travel, by which the author of a historical novel is so largely assisted in the present day. And even if he had been furnished with all these aids, would he have known how to use them?3

The Fourth Gospel, if a forgery, shows the most consummate skill on the part of the forger. It is replete with historical and geographical details; it is interpenetrated with the Judaic spirit of the times; its delineations of character are remarkably subtle; it is perfectly natural in the progress of the events, the allusions to incidents or localities or modes of thought are introduced in an artless and unconscious way, being closely interwoven with the texture of the narrative; while throughout the author has exercised a silence and a self-restraint about his assumed personality which is without parallel in ancient forgeries, and which deprives his work of the only motive that, on the supposition of its spuriousness, would account for his undertaking it at all. In all these respects it forms a direct contrast to the known forgeries of the apostolic or succeeding ages.4

I shall now proceed to investigate those phenomena of its actual contents which force us to the conclusion that it was written by a Jew contemporary with and cognizant of the facts which he relates. The fact that the writer was Jewish might be inferred with a high degree of probability. Of all the New Testament writings the Fourth Gospel is the most distinctly Hebraic.5 When a writer, as is the case in the Epistle to the Hebrews, quotes largely and quotes uniformly from the Greek Septuagint (LXX) version, this is at least an indication that he was not acquainted with the original. If on any occasion the quotations of a writer accord with the original Hebrew against the LXX, we have a right to infer that he was acquainted with the sacred language and was, in fact, a Hebrew or Aramaic-speaking Jew. Several decisive examples might be produced, but one must suffice. In John 19:37 is a quotation from Zechariah 12:10, which in the original is, “They shall look upon Me whom they pierced.” Accordingly, it is given in St. John,“They shall look on him whom they pierced.” But the LXX rendering is, “They shall gaze upon me because they insulted” where the Greek rendering has not a single word in common with John’s text.6

If therefore we had no other evidence than the language, we might with confidence affirm that this Gospel was not written either by a Gentile or by a Hellenistic Christian, but by a Hebrew accustomed to speaking the language of his fathers.7 Having thus established the fact that the writer was neither a Gentile nor a Hellenist, but a Hebrew of the Hebrews, we will proceed to inquire further whether he evinces an acquaintance with the manners and feelings, and also with the geography and history (more especially the contemporary history) of Palestine, which so far as our knowledge goes would be morally impossible with even a Hebrew Christian long after the political existence of the nation had been obliterated, and when the disorganization of Jewish society was complete.8

I cannot place the evidence fully before you at present, but my hope is that I may indicate the lines of investigation which will enable you to answer it more completely for yourselves. I will only say that we obtain from the Fourth Gospel details at once fuller and more minute on all these points than from the other three. Whether we turn to the Messianic hopes of the chosen people, with all the attendant circumstances with which imagination had invested this expected event, or to the mutual relations of Samaritans, Jews, Galileans, Romans, and the respective feelings, prejudices, beliefs, customs of each, or to the topography as well of the city and the temple as of the rural districts—the Lake of Gennesaret, and the cornfields and mountain ridges of Shechem—or to the contemporary history of the Jewish hierarchy and the Herodian sovereignty, we are alike struck at every turn with subtle and unsuspicious traces, betokening the familiarity with which the writer moves amidst the ever-shifting scenes of his wonderful narrative.9

This minuteness of detail in the Fourth Evangelist is very commonly overlooked, because our gaze is arrested by still more important and unique features in the Gospel. The striking character of our Lord’s discourses—their length and sequence, their simplicity of language, their fullness and depth of meaning—dazzles the eye and blinds us to the historical aspects of the narrative. Only by concentrating our view on these shall we realize the truth that the evangelist is not floating in the clouds of airy theological speculations, that though with his eye he peers into the mysteries of the unseen, his foot is planted on the solid ground of external fact; that, in short, the incidents are not invented as a framework for the doctrine, but that the doctrine arises naturally out of, and derives its meaning from, the incidents.10

When we turn to the city and the temple, here too we should do well to bear in mind how largely we owe the distinctive features of the topography and architecture with which we are familiar, to the Fourth Gospel. Within the sacred precincts themselves, the Porch of Solomon within the Holy City, and the pools of Bethesda and Siloam, are brought before our eyes by this evangelist alone. And when we pass outside the walls, he is still our guide. From him we trace the steps of the Lord and his disciples on that fatal night crossing the book Kedron into the garden.11

The scrupulous accuracy of the geographical and archaeological details in John’s account suggests that this text is either the most masterly piece of fiction which the genius and learning of man ever penned in any age; or you have (what universal tradition represents it to be) a genuine work of an eyewitness and companion of our Lord.12 Moreover, the familiarity of the Fourth Evangelist, not only with the site and the buildings of the temple, but also with the history, appears in a striking way from a casual allusion in Jn 2:20, as the Jewish leaders say, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple”. By comparison of several passages in Josephus, we conclude that Herod commenced his temple about 18 B.C. If we add forty-six years to the date of its commencement we are brought down to A.D. 28 or 29.

The chronology of Herod’s temple involves one considerable effort of historical criticism. The chronology of our Lord’s life requires another. St. Luke places the baptism of our Lord in or about the fifteenth year of Tiberius, which brings us to the same date by following the two lines—forty-six years or thereabouts had actually elapsed since the commencement of Herod’s building to this point in our Lord’s ministry. I am not anxious to speak with too great precision, because the facts do not allow it. The exact number might have been forty-five or forty-seven years, for fragments of years may be reckoned in or not in our calculation. But, after allowance is made for this margin of uncertainty, the coincidence is sufficiently striking.

And now let us suppose the Gospel to have been written in the middle of the second century, and ask ourselves what strong improbabilities this hypothesis involves. The writer must first have made himself acquainted with a number of facts connected with the temple of Herod. He must not only have known that the temple was commenced in a particular year, but also that it was still incomplete at the time of our Lord’s ministry. So far as we know, he could only have gotten these facts from Josephus. Even Josephus however does not state the actual date of the commencement of the temple. It requires some patient research to arrive at this date by a comparison of several passages. We have therefore to suppose, first, that the forger of the Fourth Gospel went through an elaborate critical investigation for the sake of ascertaining the date. But, secondly, he must have made himself acquainted with the chronology of the gospel history. At all events, he must have ascertained the date of the commencement of our Lord’s ministry. In the Gospel of Luke, he would find the date which he wanted, reckoned by the years of the Roman emperors. Thirdly, after arriving at these two results by separate processes, he must combine them; thus connecting the chronology of the Jewish kings with the chronology of the Roman emperors, the chronology of the temple erection with the chronology of our Lord’s life.

When he has taken all these pains, and worked up the subject so elaborately, he drops in the notice which has given him so much trouble in an incidental and unobtrusive way. It has no direct bearing on his history; it does not subserve the purpose of his theology. It leads to nothing, proves nothing. Certainly the art of concealing art was never exercised in a more masterly way than here. And yet this was an age which perpetrated the most crude and bungling forgeries and is denounced by modern criticism for its utter incapacity of criticism.13

The relative positions of Annas and Caiaphas at the time of the crucifixion have sometimes been a source of perplexity. Annas the high priest had been deposed by Gratus, the predecessor of Pilate, and after intermediate appointments, Gratus had nominated Caiaphas to the office. John is aware that Caiphas is the high priest (Jn 11:49, 18:13, 24), but he assigns an important position to Annas also, whom in some sense he recognizes likewise as high priest (Jn 18:15-16, 19, 22). On these facts we may remark, first that this unguarded, and to us unintelligible, way of speaking betokens a genuine author who does not feel the necessity of explaining what to himself is a familiar fact. As was natural with one who was “known unto the high-priest” (Jn 18:15-16), he evidently has a very clear conception of the relation of the two persons, though he has not definitely put it on paper. Secondly, so far as we are able to test the accuracy of his facts, they satisfy the test, i.e., Caiphas is the actual high priest. All this is perfectly natural for the Fourth Evangelist, supposing him to be a contemporary and eyewitness; but incredible in a forger, who could not have failed to betray himself by some slip when treading upon such delicate ground.14

I have thus endeavored to show the accuracy of the writer’s knowledge in all that relates to the history, the geography, the institutions, and the thoughts and feelings of the Jews. If however we had found accuracy, and nothing more, we might indeed have reasonably inferred that the narrative was written by a Jew of the mother-country, who lived in a very early age, before time and circumstance had obliterated the traces of Palestine, as it existed in the first century; but we could not safely have gone beyond this. But unless I have entirely deceived myself, the manner in which this accurate knowledge betrays itself justifies the further conclusion that we have before us the genuine narrative of an eyewitness, who records the events just as they occurred in natural sequence.15

Whatever touchstone we apply, the Fourth Gospel vindicates itself as a trustworthy narrative that could only have proceeded from a contemporary eyewitness, and yet, nothing has hitherto been adduced which leads to the identification of the author as the Apostle John. John is not once mentioned by name throughout the twenty-one chapters of this Gospel. James and John, the sons of Zebedee, occupy a prominent place in all the other Evangelists. In the Fourth Gospel alone, neither brother’s name occurs. The writer does once, it is true, speak of the “sons of Zebedee,” but in this passage, which occurs in the last chapter (Jn 21:2), there is not even the faintest hint of any connection between the writer himself and this pair of brothers. He mentions them in the third person, as he might mention any character whom he had occasion to introduce. Now is not this wholly unlike the proceeding of a forger who was simulating a false personality? Would it not be utterly irrational under these circumstances to make no provision for the identification of the author, but to leave everything to the chapter of accidents? On the supposition of forgery, it was a matter of vital moment that the work should be accepted as the genuine production of its pretended author. Even if our supposed forger could have exercised this unusual self-restraint in suppressing the simulated author’s name, would he not have made it clear by some allusion to his brother James, his father Zebedee, or his mother Salome? The policy which he has adopted is as suicidal as it is unexpected.16

In the opening chapter of the Gospel, there is mention of a certain disciple whose name is not given (Jn 1:35, 37, 40). This anonymous person reappears in the closing scene before and after the passion where he is distinguished as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” At length, but not till the concluding verses of the Gospel, we are told that this anonymous disciple is himself the writer: “This is the disciple who testifies of these things, and who wrote these things” (Jn 21:24).

Who then is this anonymous disciple? On this point, the Gospel furnishes no information. We arrive at the identification, partly by a process of exhaustion, and partly by attention to some casual incidents and expressions. Comparing the accounts in the other Gospels, it seems safe to assume that he was one of the inner circle of disciples comprised of two pairs of brothers, Peter and Andrew, James and John. Now he cannot have been Andrew, because Andrew appears in company with him in the opening chapter, nor can he have been Peter, because we find him repeatedly associated with Peter in the closing scenes. Again, James seems to be excluded since he became an early martyr. Thus by a process of exhaustion, we are brought to identify him with John the son of Zebedee.17

• In a newly discovered commentary on the Fourth Gospel (published by IVP in 2015), Lightfoot makes a few additional observations related to the authorship question and seems to be willing to challenge the traditional Johannine view: In the Gospel of John, the author never names himself or Jesus’ mother, Mary. The explanation for the suppression of the name of Jesus’ mother is found in 19:26, since she was entrusted to his care. The same delicate reason which would not permit him to mention his own name led him to suppress the name of her who had become his adopted mother.18 But were such fine shades of artfulness at the command of a fisher?19

• Elsewhere, Lightfoot provided an additional explanation for the author’s anonymity: The Fourth Gospel was addressed to an immediate circle of hearers and keeps them before his mind. Hence he assumes a knowledge of himself in the case of those for whom he writes. He does not give his own name, because his hearers already know his personal history.20

• Though it was disputed in his day, Lightfoot did acknowledge that there were two disciples of Jesus by the name of John known in the Early Church: Papias wrote a work entitled, Expositions of the Oracles of the Lord, in five books, of which a few scanty fragments and notices are preserved…[and in the preface he writes]: ‘On any occasion when a person came my way who had been a follower of the elders, I would inquire about the discourses…what was said by Andrew, or by Peter, or by Philip, or by Thomas or James, or by John or Matthew or any other of the Lord’s disciples, and what Aristion and the Elder John, the disciples of the Lord, say.’ This passage is introduced by Eusebius with the remark that, ‘It is important to observe that he twice mentions the name of John. The former he puts in the same list with Peter [and the rest of the Apostles] but the second John he mentions after an interval, and places among others…putting Aristion before him, and he distinctly calls him an elder, so that by these facts the account of those is proved to be true who have stated that two persons in Asia had the same name.’

The justice of this criticism has been disputed by many recent writers, who maintain that the same John, the son of Zebedee, is meant in both passages. But I cannot myself doubt that Eusebius was right in his interpretation…It will be observed that John is the only name mentioned twice, and that at its second occurrence, the person bearing it is distinguished as the elder or presbyter, this designation being put in an emphatic position before the proper name. We must therefore accept the distinction between John the Apostle and John the Presbyter, though the concession may not be free from inconvenience, as introducing an element of possible confusion.21

• Lightfoot argued that the Fourth Gospel originated in the late first century, which was a conservative position in his day, given that many German higher critics had placed it in the middle of the second century. However, in the quotation below, he seems willing to consider a much earlier date, similar to the view arrived at later by John A.T. Robinson: This is the narrative of a person who was an eyewitness of the events he relates, and who writes not half a century later, but within a very few years of the occurrence.22

For Further Study

John 5:2 There is in Jerusalem…, J.B. Lightfoot & others

Biblical Essays, J.B. Lightfoot (FREE)

The Gospel of St. John: A Newly Discovered Commentary, J.B. Lightfoot

The Identity of The Beloved Disciple, Shane Rosenthal

Authenticating The Fourth Gospel, Shane Rosenthal

Water Into Wine, Shane Rosenthal

Outside the Gospels, What Can We Really Know About Jesus?, Shane Rosenthal

Is Luke a Trustworthy Historian?, Sir William Ramsay

Which John Wrote John?, Humble Skeptic #50

J.B. Lightfoot, Biblical Essays (London: Macmillan & Co, 1893), 3-4. Reprinted in The Gospel of St. John: A Newly Discovered Commentary (Downers Grove: IVP Academic), 41-42.

Biblical Essays, 10; IVP edition, 47.

Biblical Essays, 13-14; IVP edition, 51.

Biblical Essays, 15; IVP edition, 52.

Biblical Essays, 16; IVP edition, 53.

Biblical Essays, 20; IVP edition, 56.

Biblical Essays, 21; IVP edition, 57.

Biblical Essays, 22; IVP edition, 57-58.

Biblical Essays, 22; IVP edition, 58.

Biblical Essays, 22-23; IVP edition, 58.

Biblical Essays, 29-30; IVP edition, 64.

Biblical Essays, 34; IVP edition, 68.

Biblical Essays, 30-32; IVP edition, 64-66.

Biblical Essays, 162-163; IVP edition, 296-297. Additional note: Jn 18:12 provides the best explanation, that Annas was the “father-in-law of Caiaphas.”

Biblical Essays, 36; IVP edition, 70.

Biblical Essays, 39-40; IVP edition, 72-73.

Biblical Essays, 41; IVP edition, 74.

Here Lightfoot seems to apply a form of the “protective anonymity” argument to the author himself since he had been given the responsibility of caring for Jesus’ mother. I made a similar argument on page 6 of The Identity of the Beloved Disciple. See also page 386ff of James Charlesworth’s 2019 book, Jesus as Mirrored in John.

J.B. Lightfoot, The Gospel of St. John: A Newly Discovered Commentary (Downers Grove: IVP Academic), 116.

Biblical Essays, 197; IVP edition, 324. Again, for a similar argument, see page 6 of The Identity of the Beloved Disciple.

J.B. Lightfoot, Essays on the Work Entitled Supernatural Religion (London: Macmillan, 1889), 142-144.

J.B. Lightfoot, The Gospel of St. John: A Newly Discovered Commentary (Downers Grove: IVP Academic), 197. John A.T. Robinson wrote Redating the New Testament (1976), and The Priority of John (1983).