ISRAEL: The Story Behind Jacob's New Name

Why was Jacob attacked in Genesis 32? Who was his attacker? And what is the true significance of his name change?

In the locust wind comes a rattle and hum

Jacob wrestled the angel, and the angel was overcome

— U2, “Bullet The Blue Sky” from The Joshua Tree (1987)

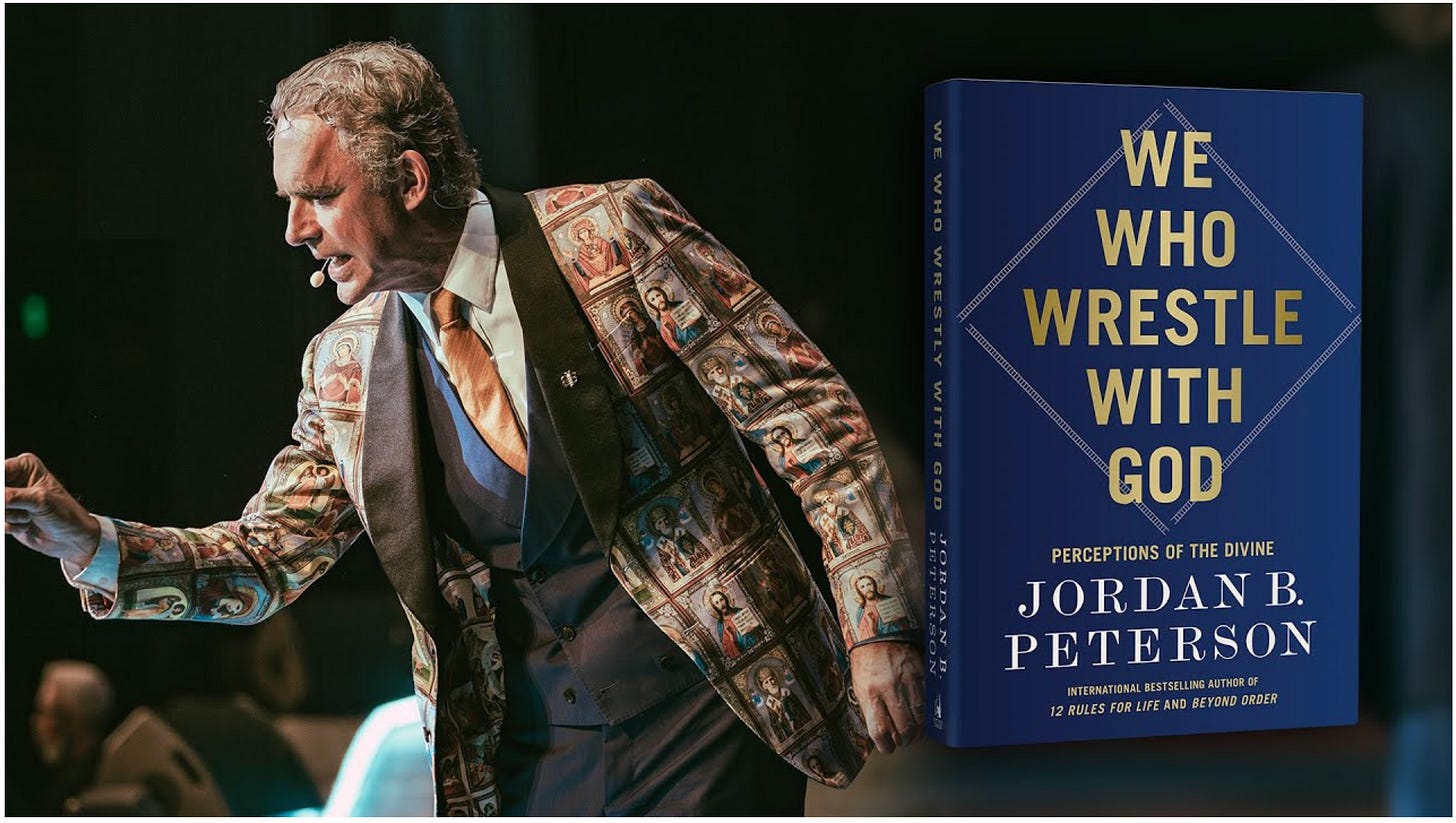

In his widely acclaimed book, We Who Wrestle With God (2024), Jordan Peterson discussed the significance of a curious scene found in Genesis 32:

On the edge of his homeland—on the very border between who he is now and who he was; on the verge of facing all the remaining consequences of who he was—Jacob of course wrestles with God, as we all do when we face the most difficult of decisions. What path will we choose? What will we allow, or call upon, to guide us? What spirit will possess us in our decision? The wrestling partner contending with Jacob is first presented as a man, but later revealed as God—the very God we wrestle with when attempting to make our difficult way forward. And who are the truly chosen people, according to this account? All those who wrestle with God honestly and forthright and prevail. Jacob sustains some genuine damage in the contest, as we are all likely to do when the most difficult decisions of our life present themselves, but he comes out of the battle firm in his conviction to do right. He fords the river, faces his estranged brother, atones for his past, and makes a productive and united peace-establishing, like the God he now worships, the order that is good. This agonizing decision transforms him so completely that, like Abram, he now has a new identity, a new name: he is now Israel, he who wrestles with God.1

Dennis Prager also acknowledged the importance of this famous wrestling match in his 2019 commentary on the book of Genesis:

It is almost impossible to overstate the importance of the meaning of the name Israel. It means ‘struggle with God.’ That God would bestow this name on his people could only mean God assumes — even expects — those who believe in him to struggle with him. There are believers who think that struggling with God such as questioning, or even doubting God is impious. But God assures us it is not only not impious but expected, and it can be meritorious.2

According to both of these authors, the ultimate point of Genesis 32 is that all of us are called to wrestle with God. When, for example, we wrestle with the implications of his existence on our lives, and on ultimate issues such as meaning or morality, then like Israel’s famous patriarch, we will ll be forever changed. It goes without question that this way of reading the story interprets Jacob’s wrestling as a good thing, worthy of both commendation and emulation. But is this the best way to understand the story?

Jacob was, of course, born to wrestle. According to Gen 25:22, he emerged from his mother’s womb grasping his brother’s heel, which is why he was given the name “Yacov,” which literally means, “heel-grabber.” Viewed negatively, it could also be interpreted to mean “supplanter,” “cheater,” or “deceiver,” which, as you read through Genesis, are all apt descriptions of Jacob’s character. In Gen 27:35, for example, Isaac clearly indicates that Jacob had deceived him when he lied about his identity and cheated his brother out of his inheritance.

The odd thing about this part of the Genesis narrative is that Jacob’s deception ends up being the basis for Israel’s inheritance of the promised land. If the patriarch had not worn his brother’s garments and lied about his identity, he (and all his posterity with him) would have been destined to inherit the dry and unfruitful land of Edom. In other words, what Genesis seems to be telling us is that the people of Israel never actually had the right to inherit the promised land. It rightfully belonged to Isaac’s firstborn son, Esau. But is this the way that God’s promise to Abraham works? Is this how the people of Israel ended up inheriting the promised land—through Jacob’s deceptive tactics?

Why should Israel’s founding patriarch be presented in Genesis as a schemer and deceiver? What other nation in the history of the world has ever presented the founder of their nation in such a brutally honest way? Before answering these questions, it’s important to note that not all commentators see it this way. According to Dennis Prager, “Jacob’s behavior is often viewed as unscrupulous. But it is quite defensible.”3 Another writer admits that “Jacob was a deceiver,” but goes on to explain that “deception is not always sinful. In this case, Jacob was a righteous deceiver.”4

In my opinion, these writers are attempting to justify Jacob’s actions because they want him—or perhaps need him—to be the hero of the story. After all, this is the man whose name is changed to Israel. He’s the patriarch who embodies the future Jewish nation, so he must be the good guy! I’m convinced, however, that Jacob is a flawed character who stands in need of redemption. In the words of Walter Brueggemann:

The narrative about Jacob portrays Israel in its earthiest and most scandalous appearance in Genesis. This narrative is not edifying in any conventional religious or moral sense. Indeed, if one comes to it with such an agenda, the narrative is offensive. But for that very reason, the Jacob narrative is most lifelike…There is a realism about this text which challenges romantic piety…The narrator wants us to know that there is a dark power at work in the life of Jacob. He is born to a kind of restlessness, so that he must always insist, grasp, and exploit…It is not argued here that he is good or honest or respectable.5

Though Jacob is presented as a deceiver and schemer, in spite of all this, he is mysteriously granted access to the promised land. In Brueggemann’s view, this is “a visible expression of God’s remarkable graciousness in the face of conventional definitions of reality and prosperity. Jacob is a scandal from the beginning. The powerful grace of God is a scandal. It upsets the way we would organize life.”6 This emphasis on grace, however, only tells one side of the story, since the blessing given to Jacob came at a cost. After all, he was allowed to enter the promised land at the expense of his brother Esau. Whereas Jacob was blessed with the fruitful land of Canaan, Esau was exiled further east, to the dry and infertile region of Edom.

As I began to wade through various interpretations of Genesis 32, it appeared to me that Jacob was frequently portrayed as the hero of the story. His wrestling match, you see, was a time in which he struggled with God and refused to let him go until he secured his blessing. Thus, the practical lesson that many people draw from this is that all of us are called to wrestle with God. With Jacob, we too should cling to God and refuse to let him go until we receive our desired blessing.

The problem with this approach is that something concrete and real has been spiritualized, which, at the end of the day, is the only way the story could be transformed into “practical application.” But when we take a close look at Genesis 32, Jacob wasn’t struggling intellectually with the implications of God’s existence or wrestling with questions of meaning or morality. In fact, he wasn’t even praying in this part of the narrative. A close study of the passages reveals that he was simply fighting for his life after being physically attacked in the dark. The fact that his name was changed to “Israel” is an important clue that the story isn’t about you or me, or how any of us can achieve victory in this life.

Since this is the first time the name “Israel” appears in the Bible, it must be important—but why? If you’re familiar with this part of Genesis, you’ll recall that Jacob was returning to the Promised Land after fleeing to Haran for twenty years after his brother had threatened to kill him for stealing his birthright. And surprisingly, as he made his way back, God was the last thing on Jacob’s mind—in fact, he appears to have been preoccupied with a different Lord altogether. According to Genesis 32:4-5, Jacob instructed his servants to send a message to his brother Esau, saying: “Thus you shall say to my lord Esau: Thus says your servant Jacob, ‘I have sojourned with Laban and stayed until now. I have oxen, donkeys, flocks, male servants, and female servants. I have sent to tell my lord, in order that I may find favor (חֵ֖ן) in your sight.’”

The Hebrew word חֵ֖ן can also be rendered “grace.” So, ironically, Jacob is focused here, not on Yahweh, but on the grace and favor of Esau. And when he hears back from his servants that his brother is coming with 400 men, Jacob is greatly afraid, and prays to God for deliverance, since in particular he fears that Esau “might come and attack me, the mothers with the children.”

Later, in verses 13-15, Jacob sends hundreds of cows, goats, and camels as an “offering” to his brother. Basically, he’s attempting to appease his brother’s anger, so that he will be accepted (Gen 32:20). Interestingly enough, this word acceptance is actually the same word we find in back in Gen 4:7, when Cain was told by God, “If you do well, will you not be accepted?” Since Cain did not end up doing what was right, but murdered his brother, he was later exiled to the land “east of Eden” (Gen 4:16). But did Jacob do what was right? Certainly not! He sinned against both his father and his brother. So why did God invite him to return to the promised land back in Gen 28 (cf. v. 15). Shouldn’t he, like Cain, be exiled from the place of God’s dwelling because of his sins? The point I believe we’re meant to see, over and over again, is that while Jacob deserves to be exiled, it’s out of God’s inexplicable mercy and grace that he’s been invited to share in the blessings of the Abrahamic promise.

Notice what happens in Gen 32:22 and following: “That night, Jacob arose and took his two wives, his two female servants, and his eleven children, and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. He took them and sent them across the stream, and everything else that he had. And Jacob was left alone.” Why does he do all this? Because he is currently afraid that his brother will come and attack him (Gen 32:11). He had already divided up his servants so that Esau would encounter wave after wave of gifts designed to turn away his anger, but just in case his brother was not appeased, he decided to move his wives and children out of harm’s way, to the opposite side of the river.

Now, in verse 24, we’re told that “A man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day.” When he was attacked in the middle of the night, what do you suppose would have gone through Jacob’s mind? It’s not difficult to guess. Based on all that we’ve been told by the narrator, he would no doubt assume that Esau finally caught up with him. In their helpful book Echoes of Exodus, Alastair Roberts & Andrew Wilson write that “It is very possible that, fording a river in the dark, Jacob thought that the man he was wrestling actually was Esau (whom he was scared of meeting)…which might explain his desperation to find out the man’s name. Only as dawn is about to break does Jacob realize that he has been wrestling with God himself.”7 John Lennox argues something similar in his book on the life of Joseph:

Jacob lingered behind and, alone in the darkness, no doubt with increasing trepidation, imagined that the next person he’d encounter will be Esau. He had presumably decided, maybe to protect his family, that he must face Esau alone. Yet he was not alone. For without warning, in the middle of the night, he found himself under surprise attack…He probably thought at first that it was his brother Esau who had failed to be modified by the gifts and had now come to fight him. His future will be decided by hand-to-hand combat in the night…Yet as the wrestling progressed, it slowly dawned on Jacob that there was something very strange about the encounter…No, this strange opponent was not Esau. It was someone altogether different.8

That Jacob initially thought he was wrestling his brother Esau is a rather fitting idea when we stop to realize that he’s been doing this very thing throughout the course of his life. Even in the womb, Jacob had wrestled with Esau. But in verse 25, we’re given the first clue that Jacob’s unnamed assailant is someone else. “When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched his hip socket, and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him.” Though this man was not able to prevail against Jacob, he seems to have had the supernatural ability to dislocate a hip by a mere touch. Now it was completely dark, so Jacob may not have been aware of what had just happened. From his perspective, perhaps all he knew was that his hip was suddenly dislocated. In verse 26, the unidentified man says, “Let me go, for the day has broken.” Jacob then replies, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

At this point, can we really argue that Jacob is demanding a blessing from God? Have we found any clues yet that the patriarch actually knows the true identity of his wrestling partner? In fact, there’s evidence that Jacob is confused about his assailant’s identity all the way up to verse 29 when he asks the man to tell him his name. So if we take this knowledge back to verse 26, I think we have good reason to believe that Jacob believed he was still wrestling with his Esau. In short, this wrestling match would resolve the conflict once and for all, and he refused to let go of his brother until Esau relinquished the right of his firstborn status.

This was the thing he’d been striving for since the day he was born. By an accident of his birth, Esau won the blessing of firstborn status, and by means of deceitful tactics, Jacob wrested the blessing from his brother (which is why Jacob was so afraid). Now that he has been attacked in the dark (just as he had feared he would be), Jacob is convinced that he must solve this conflict once and for all—by force!9

But then in verse 27, the unidentified man inquires of Jacob, saying, “What is your name?” “Jacob,” he replied—likely with some degree of hesitation. Here, I think we’re meant to consider the significance of this question in light of Jacob’s earlier deception. Back in Gen. 27:18-19, Jacob went to his father dressed in his brother’s garments. When Isaac asked who was there, Jacob lied and said, “I am Esau, your firstborn.” This, you see, was the falsehood that had enabled Jacob to secure the blessing from his brother in the first place. And here in this scene, as he is re-entering the land of promise (which was Esau’s by natural rights), God (in the form of a man) appears to Jacob and asks him to come clean about his true identity. Perhaps we can even say that he was giving Jacob a taste of his own medicine by attacking him in the dark. Just as Jacob tricked his blind father, Jacob himself is tricked in the dark into believing that Esau had finally arrived, just as he feared.

In verse 28, the man tells the patriarch, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” Jacob’s response to this announcement shows that he was completely perplexed by this statement. Even though he was told that he had striven with God, he asks the man to tell him his name. And in response to this question, God replies, “Why is it that you ask my name?’ And there he blessed him.”10 So, Jacob called the name of the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered.”

According to the prophet Hosea, “In the womb [Jacob] took his brother by the heel; And in his manhood he had power with God. Indeed, he had power over the angel, and prevailed…” (Hos 12:3). Though Hosea clearly affirms that Jacob’s wrestling partner was God, mysteriously, he also identifies him as an angel, which is a good indication that this is no ordinary angel. Rather, this is the Angel of Yahweh, who appears in various passages throughout the Old Testament (cf. Gen 16:7, 22:11, 31:11-13, 48:16, Ex. 3:2, 14:19, 23:20-23, Jdg 2:1-5, 13:17-18, etc.). After reflecting on texts of this nature, the first century Jewish writer Philo noted that “God at times assumes the likeness of the angels…as far as appearance went, without changing his own real nature, for the advantage of him who was not, as yet, able to bear the sight of the true God…those who are unable to bear the sight of God, look upon his image, his Angel Word, as himself”11 (cf. Jn 1:1-3).

So let’s think about this for a minute. Are we really to conclude that Jacob obtained the blessing (for himself and his posterity) because of his amazing wrestling abilities? Is Jacob stronger than God? Of course, he isn’t. Jacob wasn’t blessed because of his strength or his tenacity. Instead, when he stopped to consider what had happened—that he had unknowingly been fighting with his creator—he was shocked and said, “I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered” (Gen 32:30). If this really was God human form, then he could have conquered Jacob with a single word or touch. And therefore, the only solution to this bizarre passage is to say that Jacob obtained his blessing, not because of his superhuman strength, but rather, because God, in his gracious providence, allowed it to happen.

Recall once again the principle discussed earlier, that Jacob received the Abrahamic blessing at the expense of his brother Esau, who, as a result of his brother’s treachery, ended up inheriting the infertile desert region of Edom. It seems more than a little strange that Jacob should be awarded the promised land as a result of his deceitful tactics. But perhaps here in chapter 32, God will set things right. Yet, what we find instead is that God allows Jacob to prevail over him in this unexpected wrestling match. And this is the scene in which the patriarch is given the new name, “Israel.” This is how the people of Israel were granted access to the promised land. It all comes down to this moment in redemptive history, which points not to Jacob’s strength, but to God’s weakness and condescending grace (1 Cor 1:25).

In his commentary on this passage, Augustine offered the following insight:

Jacob held his brother’s foot who preceded him in his birth, and…because he held his brother’s heel, he was called Jacob, that is, “supplanter.” And afterwards…the Angel wrestled with him in the way. What comparison can there be between an Angel’s and a man’s strength? Therefore it is a mystery, a sacrament, a prophecy, a figure; let us therefore understand it. For consider the manner of the struggle too. As he wrestled, Jacob prevailed against the Angel. Some high meaning is here. And when the man had prevailed against the Angel, he…kept hold of Him whom he had conquered [saying], “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” When the conqueror was blessed by the Conquered, Christ was prefigured. So then that Angel, who is understood to be the Lord Jesus, said to Jacob, “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel shall your name be”…Such great power had this Conquered One, that a single touch to Jacob’s thigh, made him lame. It was then by His Own will that He was conquered. For He “had power to lay down” His strength, “and He had power to take it up again.” He was not angry at being conquered, just as he was not angry at being crucified.12

I’m convinced that Augustine was on to something here. Because of the events of Genesis 32, the descendants of Jacob would later come to be known as “the people of Israel.” In other words, this is a monumentally significant passage in the history of redemption, which is a fact that is often overlooked by many modern commentators. So are we really to believe that the main point of this passage is that God’s people should pray with tenacity and refuse to give up until they get their desired blessing? Surely there’s more to the story than obtaining our best life now?

Though most contemporary writers and scholars suggest that Jacob’s new name Israel, means “he who struggles with God,” notice what we find when we take a look at the way much older translations rendered verse 28 of Genesis 32:

Greek Septuagint (LXX): “Thy name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel shall be thy name; for thou hast prevailed with God, and shalt be mighty with men.”

Aramaic Targum: “Your name will not be called Jacob anymore, but Israel, for you are great before the Lord and with men, and have overcome.”

Latin Vulgate: “Your name will not be called Jacob, but Israel, for if you have been strong against God, how much more will you prevail against men?”

Syriac Peshitta: “Your name will no longer be called Jacob but Israel because you exercised strength with an Angel, and with men you have been granted power.”

In each of the above cases, the word Israel was interpreted to mean, not “one who struggles with God,” but rather, “one who prevails over God.” But this interpretation only serves to highlight the strangeness of Jacob’s inexplicable victory. Though he had won the wrestling match, Jacob did so without realizing that he had actually been victorious over God himself. But how can a man defeat God? The only way this is possible is if God himself allows it to happen, just as a father may sometimes allow himself to be defeated while playfully wrestling with his own children. When Jacob finally realized that God was his wrestling partner, that’s when he ended up confessing that his life had been “delivered.”

This is why I am convinced that Augustine’s interpretation is worth considering. According to Jacob’s confession, he didn’t actually defeat God by his own strength and tenacity. Instead, in that moment, he realized that he had actually been rescued. The fact that his name was changed to Israel is therefore playful and unexpected—something meant to inspire curiosity, reflection, and wonder. Jacob is now Israel, the man who defeated God in a wrestling match!

In a sermon on Psalm 45 Augustine added that when Jacob “wrestled with the Angel, and ‘prevailed,’ and had been blessed by Him over whom he prevailed, his named was changed, so that he was called ‘Israel’; just as the people of Israel ‘prevailed’ against Christ, so as to crucify Him, and nevertheless were (in those who believed in Christ) blessed by Him over whom they prevailed.”13 He also taught something similar in a sermon on Psalm 80:

For when others said ‘If he is the Son of God, let him come down from the cross,’ He seemed to have no power: the persecutor had power over him: and he showed this in advance when Jacob too prevailed over the angel. A great sacrament! He was conquered, and blessed the conqueror. Conquered, because he willed it; in flesh weak, in majesty strong...Having been crucified in weakness, he rises in power.”14

The fact that Jacob was renamed Israel just as he was re-entering the promised land is also significant. This story helps us to see that from the very beginning of the story, the people of Israel were permitted to enter God’s country, not because they deserved it, but because of God’s gracious invitation (cf. Dt 9:4). But this story also hints at something greater yet to come. Though Jacob is just one man, here in this mysterious encounter, he seems to embody the actions of the future nation. In the fullness of time, Israel’s leaders would end up rejecting (Is 53:3) the very one who came to redeem all mankind (Is 52:9-10). Nevertheless, what they meant for evil, God ordained for good in order to bring about a great redemption (Gen 50:20, Acts 2:22-23).

In John chapter 11, there’s a report of a man standing up during a meeting of the Sanhedrin and saying, “If we let Jesus go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation.” Caiaphas, the high priest, then responded by saying, “Don’t you understand that it is better for you that one man should die for the people, not that the whole nation should perish?” This is what Genesis 32 is ultimately hinting at. Like the famous patriarch, the children of Israel are still found striving, scheming, and plotting (Mt 26:4; cf. Ps 2:1-3). Fearing the Romans more than God himself (Gen 32:11), the leaders of the Sanhedrin had no clue that the person they were about to arrest was the Lord of all creation, robed in flesh. After all, “he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him” (Is. 53:2).

By delivering him over to be crucified, these men believed they were securing for themselves the ability to remain in the promised land. And yet, it was through this act of treachery that anyone is granted access to the ultimate land of rest. According to Augustine, all of this was foreshadowed in Genesis 32.

At the end of the day, this story is not about the power of Jacob’s striving or grasping, because he is not the hero of this story. Jesus, the one who “did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped” (Phil 2:6), is the focus of Genesis 32. At this point, I should be clear that I’m not advocating a form of typology, since in the standard Christian interpretation of this passage, it was Jesus himself who appeared to Jacob by the Jabbok River. In other words, he wasn’t merely hinted at in this scene but personally showed up and did some of the hinting! In his comments about this passage, Clement of Alexandria wrote that “Jacob called the name of the place, ‘Face of God’…The face of God is the Word by whom God is manifested and made known.”15 If, according to Ex 33:20, no one can see God’s face and live, how is it that Jacob survived? This is explained more fully in the New Testament: “No one has ever seen God,” John says in his opening prologue, “the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known” (Jn 1:18).

The best way to account for the mysterious events recorded in Genesis 32 is to focus on the way those themes are ultimately resolved in the greater story of redemption. According to Lk 24:27, Jesus specifically taught his disciples to read the Old Testament this way, “beginning with Moses.” Because all of us are like Jacob, none of us has the right to enter God’s country standing on his own merit. As Isaiah says, “All we like sheep have gone astray…” (Is 53:6). However, if like Jacob we wear the garments of the firstborn, the garments of the one who did have the right to inherit the land, if we put on his robe (Is 61:10, Lk 15:22), then, and only then, will we be granted access to the ultimate land of rest. But of course, all this comes at a cost. Jesus was cursed so that we could be blessed. In order that we could be brought near, he was exiled “outside the camp” (Heb. 13:12-13). He died that we may live.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the original creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast, which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Modern Reformation, Core Christianity, Heidelblog, and others. An earlier version of this article was published on the White Horse Inn blog back in 2021.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Articles

Finding Christ in All of Scripture (PDF), Shane Rosenthal

Justin Martyr on the Importance of Fulfilled Prophecy, Shane Rosenthal

Isaiah’s Prophecy of the Messiah’s Birth, Shane Rosenthal

The Bethlehem Prophecy: An Exploration of Micah 5:2, Shane Rosenthal

The Date of John’s Gospel, Revisited, Shane Rosenthal

The Implications of 70 AD on the Gospels & Acts, Shane Rosenthal

A Pre-70 Date for the Gospels & Acts, Shane Rosenthal

Podcast

The Angel of Yahweh, Shane Rosenthal with Van Dorn & Foreman

How to Read & Interpret the Bible, Shane Rosenthal with Mike Brown

How Did Jesus View the OT? Shane Rosenthal with Jason DeRouchie

Jacob’s Ladder, Shane Rosenthal with Richard Bauckham and Michael Horton

Babylon, Shane Rosenthal

Decoding The Prophecies of Daniel, with Daniel Boyarin & Craig Evans

Video

Jacob Wrestles with God, You Can Handle the Truth

Who is Luke’s Key Witness? Shane Rosenthal & Frank Turek

Jordan B. Peterson, We Who Wrestle With God (New York: Portfolio / Penguin, 2024), 292.

Dennis Prager, The Rational Bible: Genesis (Washington DC: Regnery Faith, 2019), 386-387.

Ibid., 301.

Zachary Garris, “Jacob—The Righteous Deceiver,” March 18, 2018

Walter Brueggemann, Genesis (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1982), 204, 214, 219.

Ibid., 217.

Alastair Robers and Andrew Wilson, Echoes of Exodus (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2018), 77.

John Lennox, Joseph: A Story of Love, Hate, Slavery, Power, and Forgiveness (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), 48.

According to some commentators, conflicts in the ancient world were often settled through wrestling matches.

Notice how the Angel of Yahweh adds a little more information in Jdg 13:17-18. Then both texts should be compared to the great messianic promise of Isaiah 9:6.

Philo of Alexandria, Dreams 1:238-239.

Augustine, “Sermons on Selected Texts of the New Testament” (Sermon 72.3) in Nicene & Post-Nicene Fathers (1), Vol 6.

Augustine, “Exposition on the Psalms” (45.18) in Nicene & Post-Nicene Fathers (1), Vol 8.

Augustine, “Exposition on the Psalms” (80.2) in Nicene & Post-Nicene Fathers (1), Vol 8.

Clement of Alexandria, The Instructor (Book 1, Chapter 7) in The Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. 1.

Thank you, Shane, for this helpful article. Two things stood out in particular: Augustine's insights, and your imagery of a father wrestling with a child where he "lets" him win.

Great perspective, Shane. Wow, God’s grace just pierces through the Hebrew Scriptures! Recently was made aware of a similar point in Jesus’ parable in Matt 20.1-16, and how we easily get offended with the landowner who pays the last hour workers the same wage as the ones there all day. Naturally, we think in terms of getting paid, fairly, by the hour… but the parable is all about God’s radical grace! When we compare ourselves with others, we automatically miss how amazing it is that God lavishes his grace on us, like those who came at the ‘end of the day’ (Gentiles). Grateful for the research and work you put into your posts.