The Implications of 70 AD on the Date of the Gospels and other NT Texts

Many prominent NT scholars (both liberal and conservative) have argued that the Gospels and other NT books were written before the fall of Jerusalem.

“If chronology is the proverbial backbone of history, then the study of Christian origins has developed scoliosis.”

— Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament

In a recent article, I reported that Cambridge professor George van Kooten published an essay this past May in which he argued for an earlier dating of John’s Gospel. Though most NT scholars date this ancient text to the latter part of the first century (typically around the 80s or 90s), Dr. van Kooten presented evidence that it was written sometime before the start of the Jewish War, likely around 65 AD. One of the reasons this is surprising is that Dr. van Kooten doesn’t appear to be motivated by an overall conservative outlook. In fact, in the very same article in which he called for a pre-70 date of the Fourth Gospel, he also argued that the Gospel of Luke should be dated to the early 90s, and perhaps as late as 130 CE.1

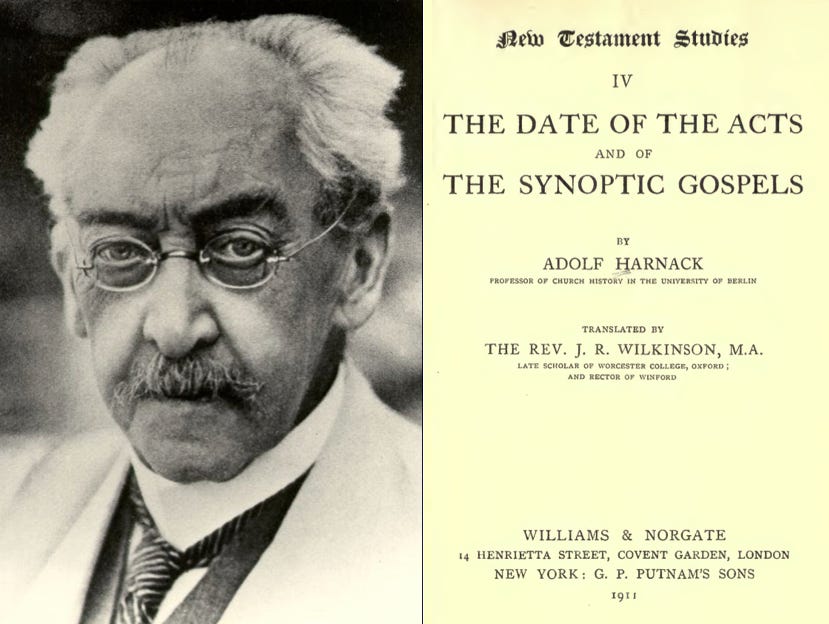

In my upcoming podcast series on the Gospel of Luke, which is set to launch sometime in August, you’ll hear from a variety of NT scholars and authors who see things a little differently. In their assessment, there are very good reasons to believe that the two-volume work of Luke/Acts was written well before the destruction of Jerusalem. In fact, when the liberal German theologian Adolph von Harnack focused on the implications of this evidence, it forced him to reassess the dates, not only of Luke, but of Matthew and Mark as well.

For example, as early as 1909, von Harnack observed the following in his study of the book of Acts:

How remarkable it is that a vivacious storyteller like St. Luke should remain so ‘objective’ that, simply because he is dealing with the times before A.D. 66, he gives no hint of the tremendous change that came with the year A.D. 70! Though in [Acts] 11:28 he expressly notices that the prophecy of the [Jerusalem] famine was actually fulfilled in the reign of Claudius; yet this historian nowhere says that the prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem was fulfilled, and…does not think of referring to the terrible judgment that had actually come upon the nation.2

In von Harnack’s estimation, Jesus’ teaching in the Olivet Discourse recorded in all three of the Synoptic Gospels was to be considered “more easily intelligible if it were written before the destruction of Jerusalem than on the contrary assumption.”3 In the end, he concluded that Luke’s two-volume work had already been written by “the beginning of the seventh decade of the first century.”4 Just two years later, however, after thinking through the implications of his thesis, von Harnack released yet another book on the very same topic. In this second book, the German scholar conceded that:

The more clearly we see that the trial of St Paul, and above all his appeal to Caesar, is the chief subject of the last quarter of the Acts, the more hopeless does it appear that we can explain why the narrative breaks off as it does, otherwise than by assuming that the trial had actually not yet reached its close. It is no use to struggle against this conclusion. If St Luke, in the year 80, 90, or 100, wrote thus he was not simply a blundering but an absolutely incomprehensible historian!…Not only is the slightest reference to the outcome of the trial of St. Paul absent from the book, but not even a trace is to be discovered of the rebellion of the Jews in the seventh decade of the century, of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, of Nero’s persecution of the Christians, and of other important events that occurred in the seventh decade of the first century.5

As Jonathan Bernier tells the story, “Harnack twice revised his estimate for the date of Acts, each time downward. Starting from a date ca. 93, he eventually concluded that the book must predate 70.” Though some claim that at its root, this is an argument from silence, in Bernier’s estimation, it is better viewed as an argument from presence:

[I]ndeed, the presence of an extended (eight chapters!) discussion of Paul’s legal challenges and an ending that leaves said challenges unresolved. And Harnack makes a strong case. It is frankly difficult to either disagree with or improve upon his argument. Either Acts was completed ca. 62, when the Acts narrative ends with Paul in Rome, or Luke’s aims in these last chapters remain opaque.6

In turn, the implications of this shift in von Harnack’s thinking about the ending of Acts had a dramatic effect on his dating, not only of Luke, but of Matthew and Mark as well. “If two years after the arrival of St. Paul in Rome the Acts was already written, then the date of the Lukan gospel must be earlier, and that of the gospel of St. Mark earlier still.”7 When it came to the Gospel of Matthew, he believed that it should be dated slightly later, but “in close proximity with the destruction of Jerusalem.”8

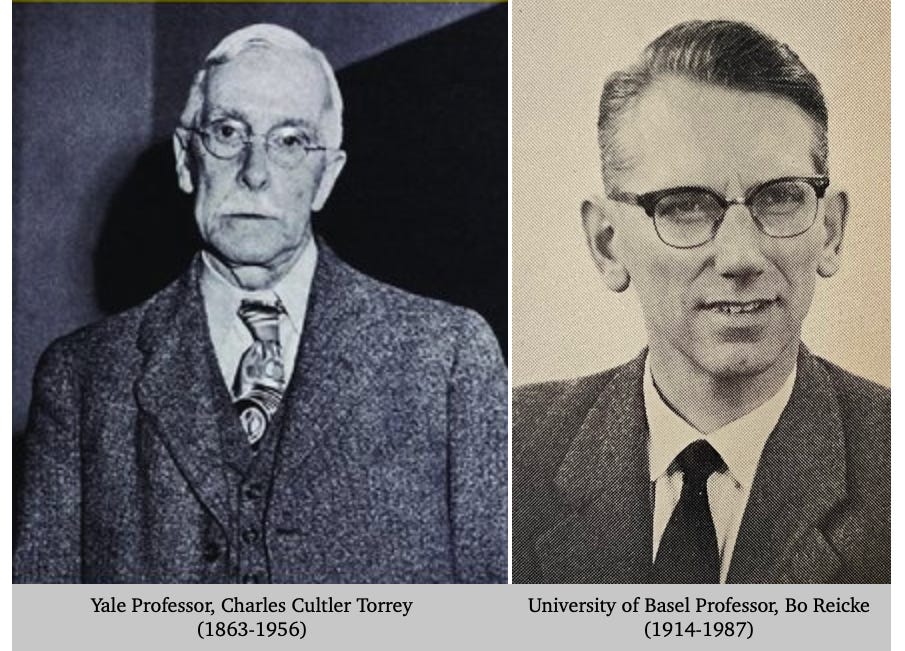

In 1947, Yale professor Charles Cutler Torrey made a similar observation:

It is perhaps conceivable that one evangelist writing after the year 70 might fail to allude to the destruction of the temple by the Roman armies (every reader of the Hebrew Bible knew that the Prophets had definitely predicted that foreign armies would surround the city and destroy it), but that three (or four) should thus fail is quite incredible. On the contrary, what is shown is that all four Gospels were written before the year 70. And indeed, there is no evidence of any sort that will bear examination, tending to show that any of the Gospels were written later than about the middle of the century. The challenge to scholars to produce such evidence is hereby presented.9

According to Torrey, there are no allusions to the destruction of the Temple in the Gospels and Acts, and Jesus’ teaching about the destruction of the temple in the Synoptic Gospels is wrongly interpreted by scholars as a past event placed on Jesus’ lips as a prophecy, since he was merely repeating the words of the OT prophets, “as can easily be demonstrated in detail. Foreign armies will surround Jerusalem (Zech. 14:2); the city and the temple will be destroyed (Dan. 9:26); two-thirds of the people of the land will be butchered (Zech. 13:8); etc.”10

Therefore, when scholars argue that Jesus’ wording in Luke 21:20—“When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies”—reveals to us that Luke wrote his Gospel sometime after the Jewish war, Torrey writes that “it is time to enter a strong protest. Every Jew knew that the beginning of the end was to be the capture and devastation of the city by Gentile armies. This could have been learned unmistakably from Daniel, even if Zech. 14:2 had not said it in so many words!”11

In his 1962 book, The Gospel of Luke, Bo Riecke, professor of NT at the University of Basel, agreed with the conclusions of von Harnack that the unexpected ending of Acts pointed to a significantly earlier date:

If we judge the question of the origin of Luke’s two writings independently of current theories or traditions and have regard only to internal evidence, this passage will obviously be of conclusive importance in dating the Gospel. It appears that the author had completed his account of the events which had taken place soon after the conclusion of the two-year period, say A.D. 63 or 64. For if Luke had written at a considerably later date, more would surely have been said about Paul. To hypothesize a lost or uncompleted continuation of the Acts of the Apostles is an unsatisfactory evasion. There is not the slightest suggestion in the existing text of Paul’s later fate and his martyrdom in connection with the persecution of Nero in A.D. 65, a natural inclusion if the book had been written later. The only simple and straightforward explanation of its abrupt conclusion is to assume that it was written soon after the end of the period which it describes. If this suggestion does not harmonize with the commonly accepted views of the origin of the Synoptics, we shall have to change our attitude toward these. One clear fact is a more valuable basis to go on than a whole lot of uncorroborated assumptions. So there are valid reasons for dating the writing of the Gospel of Luke and Acts to some time after 62.12

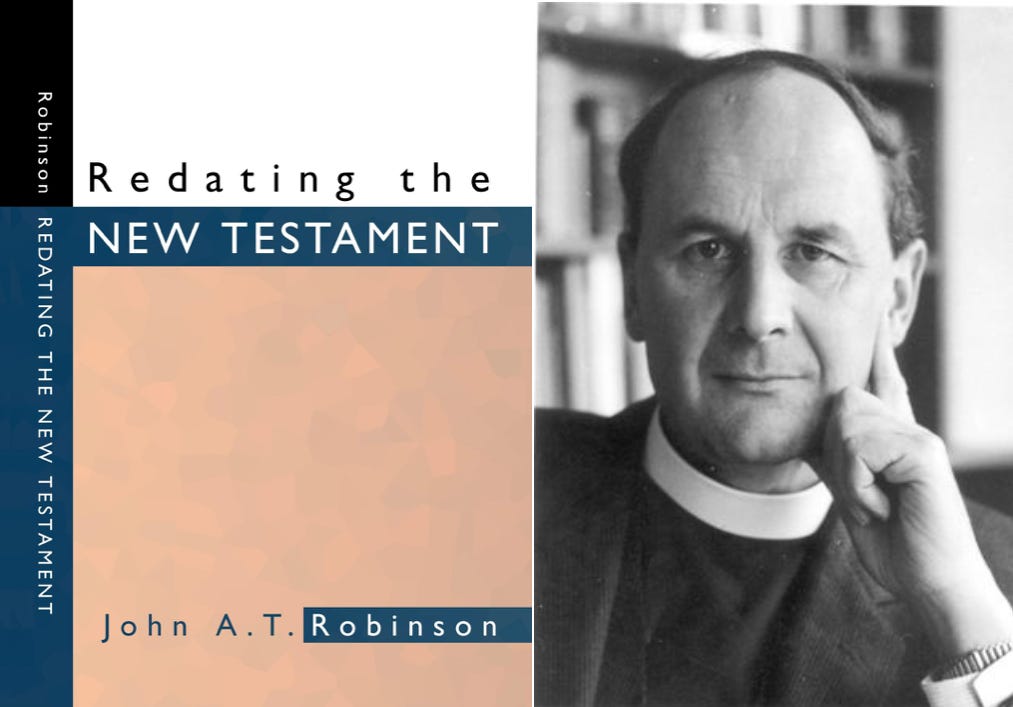

John A.T. Robinson was a liberal theologian who lectured at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1969 to 1983. But after wrestling with the views of Adolph von Harnack, particularly relating to his dating of Acts and the Synoptic Gospels, Robinson concluded that the entire foundation upon which the Gospels were traditionally dated over the past century or more was built on a host of mistaken assumptions. Therefore, he concluded that it was time for a fresh examination of the chronology of the entire NT.

No one since Harnack has really gone back to look at it for its own sake or to examine the presuppositions on which the current consensus rests. It is only when one pauses to do this that one realizes how thin is the foundation for some of the textbook answers and how circular the arguments for many of the relative datings. Disturb the position of one major piece and the pattern starts disconcertingly to dissolve.13

As Robinson reveals in his 1976 book, Redating the New Testament, at some point he began to ask himself “why any of the books of the New Testament needed to be put after the fall of Jerusalem in 70.”14 So, almost as “a theological joke,” he decided to push this hypothesis as far as it would go. In the end, he concluded that all four Gospels were written sometime between 40-65 AD, and that the entire NT, including the book of Revelation, had been penned by 70.15

One of the key factors that led to this conclusion was the strange ending of Acts. In the last two verses, Luke writes that “Paul stayed two whole years in his own rented house, and received all who were coming to him, preaching the Kingdom of God, and teaching the things concerning the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness, without hindrance” (Acts 28:30-31). But why does Luke end his narrative this way? According to Robinson,

Various reasons have been advanced to explain this ending. It is said that it suits Luke’s apologetic purpose to close with Paul preaching ‘openly and without hindrance’ to the Roman public. But this must surely have been rendered less than cogent for Theophilus by glossing over in silence the common knowledge that he and Peter and a vast multitude of other Christians in the city had within a few years been mercilessly butchered. There is no hint of the Neronian persecution…Nor is there any shadow in Acts of the impending Jewish revolt, let alone of the destruction of Jerusalem to bear out the earlier prophecies of the Gospel.16

In the end, Robinson concluded that if Paul’s trial had already taken place and the outcome was known, it was “surely incredible, as Harnack says, that no foreshadowing or prophecy of it after the event is allowed to appear in the narrative.”17 Thus, in his view, “the burden of proof would seem to be heavily upon those who would argue that it does come from [a later period].” After reflecting on internal evidence of this kind from both Luke and Acts, Robinson concluded that “Acts was completed in 62 or soon after, with the Gospel of Luke some time earlier.”18

This conclusion, however, had a host of “repercussions.” Since most NT scholars argue that Luke used Matthew and Mark as two of his sources, the redating of Luke necessarily pushes the dates of those other gospels earlier than 62. But in Robinson’s view, this was a non-starter for scholars who wished to hold on to the traditional dating scheme. In fact, he argued that it was “the difficulty of squaring this conclusion with the dominant view [that] weighed most heavily against its acceptance.”19

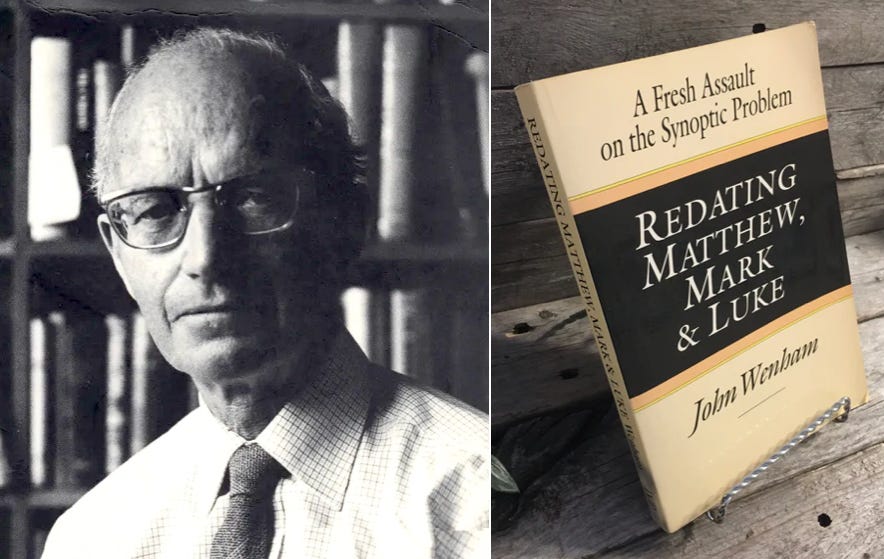

Redating Matthew, Mark & Luke by NT scholar John Wenham is another important (but often overlooked) study of this topic. In the author’s words, the title is “a conscious echo of J.A.T. Robinson’s Redating the New Testament,” and the book’s starting-point has to do with “the strange ending of the Acts of the Apostles, concerning which Robinson has revived the argument which so powerfully moved A. Harnack.”20 Similar to the observations made above, Wenham notes that,

For some nine chapters the book of Acts has been concerned, first with the story of Paul’s fateful visit to Jerusalem which led to imprisonment and his appeal to Caesar, and then with the story of his journey to Rome. We are eager to know what happened at Paul’s trial, but the author never tells us. He just says: ‘he lived there two whole years at his own expense, and welcomed all who came to him...’ The only satisfying explanation of the writer’s silence concerning the trial, it will be argued, is that when Luke wrote these closing lines it had still not taken place. In other words the end of the story gives the date of the book: c. 62. But Acts was preceded by an earlier treatise, the Gospel according to Luke, and this, it will be argued, can be dated with some assurance in the early 50s.21

As a result of this move, Wenham concluded that Matthew should be dated to around 40 AD and Mark to around 45. Many scholars reason that these dates are much too early since there is a reference to the destruction of Jerusalem in Jesus’ Olivet Discourse, but Wenham responds to this objection by saying that none of the Synoptic Gospels containing that discourse “tells us that Jesus’ prophecy was fulfilled. Luke tells us of the fulfillment of Agabaus’ prophecy of worldwide famine (Acts 11:28), but of the fulfillment of this disaster, which to the Jews was incomparably greater, he says not a word.”22

When asked to comment on John A.T. Robinson’s view related to an earlier date of the four Gospels, Bart Ehrman responded on his blog by saying that “The big problem everyone has had with it is that passages like Mark 13, Matthew 24-25, and Luke 21 seem to presuppose the destruction of the Temple.”23 But as we’ve already seen, Jesus was merely restating the words of the OT prophets. What’s particularly striking (and one that wasn’t addressed by Ehrman) is the fact that the destruction of Jerusalem is never presented in the Gospels, or anywhere else in the NT for that matter, as a completed event.24

Why does the book of Acts end so abruptly without ever mentioning the outcome of his trial, his subsequent missionary activity, or his second trial in which he was condemned to death? Why is there no mention of Paul’s final words before he was executed at the command of Nero? According to Ehrman, Luke ended Acts where he did because “his entire thesis is that nothing could stop Paul and the preaching of his gospel. Narrating his death would have worked against his main point.”25 But if Paul had already been executed, then something did stop him, and if Theophilus was aware of this fact, wouldn’t that have worked against Luke’s main point?

“If chronology is the proverbial backbone of history,” Jonathan Bernier wisely observed, “then the study of Christian origins has developed scoliosis.”26 David Rohl has made similar observations about many of the distortions built into the traditional dating of Egyptian chronology, together with all their related OT synchronisms.27 The fact that George van Kooten is now calling for an earlier date of the Fourth Gospel is perhaps a sign that things are beginning to change. But his suggestion that Luke was likely written sometime between 93-130 is a sign that we still have quite a long way to go.

To read an exhaustive selection of quotes by scholars and commentators over the centuries advocating a pre-70 date for the Gospels and Acts, click here.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast, which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Logia, Core Christianity, Beautiful Christian Life, and many others. His forthcoming book, Luke’s Key Witness, is due out later this year.

RELATED RESOURCES

Articles

A Pre-70 Date for Revelation? Shane Rosenthal

A Pre-70 Date for the Gospels & Acts, Shane Rosenthal

The Date of John’s Gospel, Revisited, Shane Rosenthal

John’s Gospel: Are We Witnessing a Paradigm Shift? Shane Rosenthal

John 5:2 “There is in Jerusalem…” Shane Rosenthal

Authenticating The Fourth Gospel, Shane Rosenthal

The Identity of the Beloved Disciple, Shane Rosenthal

Outside the Gospels, What Can We Know About Jesus? Shane Rosenthal

Water Into Wine?, Shane Rosenthal

Books

Redating the New Testament, John A.T. Robinson

Redating Matthew, Mark & Luke, John Wenham

Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament, Jonathan Bernier

The Date of Acts & The Synoptic Gospels, Adolph von Harnack

Can We Trust The Gospels? Peter J. Williams

Luke’s Key Witness, Shane Rosenthal

Episodes

Is John Late & Unreliable? Humble Skeptic #51 with Daniel Wallace

Questioning Conventional Wisdom, HS #13 with David Rohl

Did the Exodus Ever Happen? HS #69 with David Rohl

Questioning The Fourth Gospel, HS #49 with Richard Bauckham

Which John Wrote John? Humble Skeptic #50

The Jesus of History, Humble Skeptic #12

Stories of Jesus: Can They Be Trusted? HS #61 with Peter J. Williams

Are the Gospels History or Fiction? Humble Skeptic #52 with John Dickson

Faith Founded on Facts, Humble Skeptic #15

George van Kooten, “An Archimedean Point for Dating the Gospels,” Novum Testamentum, 67(3), 310. This article was published on May 29th, 2025, and can be found here.

Adolph von Harnack, The Acts of the Apostles (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 294. Emphasis in original.

Ibid., 295.

Ibid., 293.

Adolph von Harnack, The Date of The Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels (London: Williams & Norgate, 1911), 97-99.

Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2022), 62.

Harnack, The Date of The Acts, 125.

Ibid., 134.

Charles Cutler Torrey, The Four Gospels (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1947), xiii.

Ibid., 256-257.

Ibid., 283-284.

Bo Reicke, The Gospel of Luke (Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1964), 25-26. This work was first published in German in 1962.

John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 9.

Ibid., 10.

Ibid., 352.

Ibid., 89-90.

Ibid., 91.

Ibid., 92.

Ibid.

John Wenham, Redating Matthew, Mark & Luke (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1991), xxii.

Ibid.

Ibid., 224.

https://ehrmanblog.org/new-boxes-oral-traditions-and-the-dates-of-the-gospels/

Robinson, Redating the New Testament, 13.

https://ehrmanblog.org/new-boxes-oral-traditions-and-the-dates-of-the-gospels/

Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament, 1.

I discussed this with Dr. Rohl on episode 69.