Simon of Cyrene: An Intriguing Archaelogical Discovery

A first-century ossuary discovered in Jerusalem may provide external confirmation for the existence of the man who carried Jesus' cross to Golgotha

Simon of Cyrene is one of the lesser-known characters from the Gospels, but to anyone familiar with the passion narratives, he’s the man the soldiers seized and compelled1 to carry the cross (cf. Mt 27:32, Mk 15:21, Lk 23:26), presumably because Jesus could no longer carry it himself. It’s a dramatic scene that has been depicted in countless paintings and sculptures down through the centuries.

The ancient city of Cyrene was situated near modern-day Shahhat, Libya, which is roughly 500 miles west of Alexandria, Egypt. According to Josephus, in the 4th century BC, Ptolemy (who formerly served under Alexander the Great) “sent a party of Jews to inhabit the region of Cyrene”2 and by the first century, Jewish citizens had become a fourth of the entire population.3 Acts 2:10 tells us that many of those who came to Jerusalem for the feast of Pentecost were from “Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene” (see also Acts 6:9, 11:20, and 13:1 for related references to this Jewish community). Simon was from this region and had just arrived in Jerusalem to celebrate the feast of Passover when he was conscripted into service by the Roman soldiers.

Mark’s Gospel is unique in that it not only mentions Simon, and the role he played on the day of Jesus’ crucifixion, but it also records the names of his two sons: “They forced a man coming in from the country who was passing by to carry Jesus’s cross. He was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus” (Mk 15:21). Many scholars have argued that Mark may have mentioned these names because his readers were familiar with them.4 According to Jack Finegan,

That the members of the family became Jewish Christians is [likely], for Mark’s reference to Alexander and Rufus suggests that they were well known in Christian circles, and it is therefore also not unlikely that the Rufus of Mk 15:21 is the same as the Rufus who is greeted as ‘eminent in the Lord,’ together with his mother, by Paul in Romans 16:13.5

This connection gains additional support from Irenaeus, who says that, “Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter.”6 If Mark, therefore, originally wrote his Gospel for the Christian believers in Rome, it makes sense to suggest that Alexander and Rufus received a mention because they were known to that community, which Paul’s greeting in Rom 16:13 also seems to confirm. Richard Bauckham argues that by referencing Alexander and Rufus, “Mark is appealing to Simon’s eyewitness testimony, known in the early Christian movement not from his own firsthand account but from that of his sons [who told] their father’s story of the crucifixion of Jesus.”7

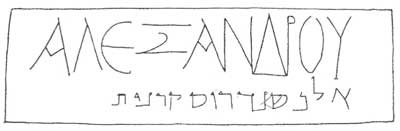

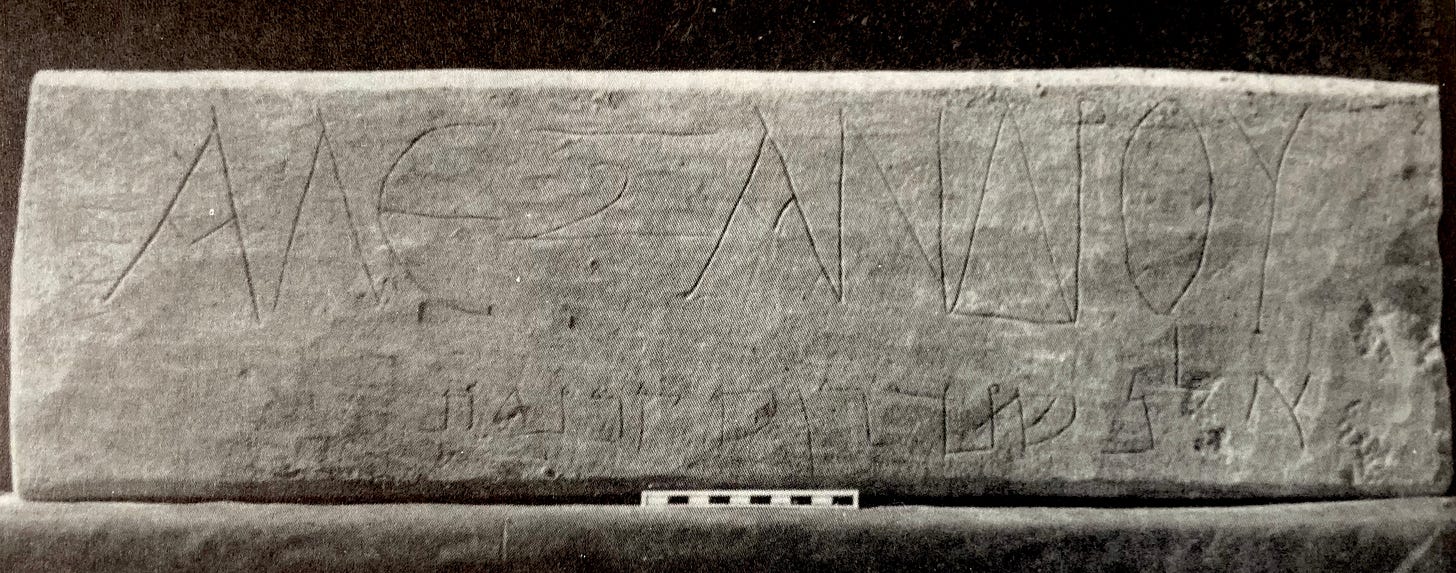

In his book, The Archaeology of the New Testament (1992), Jack Finegan mentions the discovery of a fascinating ossuary (which is an ancient burial box used to store bones) located on the Mount of Offense in Jerusalem. This ossuary belonged to a man by the name of Alexander, and according to Finegan, “The name is incised neatly in both Greek and Hebrew on the lid…together with the name Simon…and this Simon is evidently the father of Alexander.”8 What is particularly striking is the fact that this Simon also happens to be from the region of Cyrene.

The word “Cyrene” is inscribed in Hebrew on this ossuary, although unfortunately, it was misspelled, which has led some scholars to have reservations about its true meaning. But in a 2021 blog post, liberal New Testament scholar James Tabor observed that “Archaeologists were able to determine this was a family tomb for a family of Jews from Cyrene, and it was dated to the 1st century CE.” All those buried in this area of the tomb could therefore confidently be “identified as Cyrenians.”9 In fact, Finegan says that one of the other ossuaries found in this tomb belonged to a “Sara of Ptolemais,” who also happened to be “the daughter of Simon.” “This Sara,” he observes, “must be the sister of Alexander, son of Simon, [whose home] was probably the Ptolemais in Cyrenaica.”10

Tom Powers wrote an in-depth article discussing this subject for Biblical Archaeology Review back in 2003, in which he writes:

When we consider how uncommon the name Alexander was, and note that the ossuary inscription lists him in the same relationship to Simon as the New Testament does and recall that the burial cave contains the remains of people from Cyrenaica, the chance that the Simon on the ossuary refers to the Simon of Cyrene mentioned in the Gospels seems very likely.11

When Powers revisited this subject three years later, he noted that Tal Ilan, the author of The Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity, believed this identification had merit.“Based on the context of the find, the inscriptions on the chests, and her own statistical analysis of the names, she says it is ‘very likely.’” Liberal New Testament scholar, James Tabor, arrived at a similar conclusion: “The name Simon is fairly common among Jews of this period but the name Alexander much less so—and this Alexander, like his father, is from Cyrene.”12

In the first edition of Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, Richard Bauckham discussed the importance of Simon of Cyrene, since he serves an important role as an eyewitness to Jesus’ crucifixion. This ends up being particularly significant for Mark’s Gospel, since at this point in the narrative, all the disciples have fled after Jesus’ arrest. As Bauckham explains,

In the first place, readers of Mark who wondered about the sources of Mark’s information would readily suppose that most of his narrative derives from the circle of the Twelve…who participate in most of the events until all but Peter leave Mark’s narrative, never to reappear in person, at 14:50…Mark’s readers are also likely to have supposed that, among the Twelve, Peter especially stands behind Mark’s narrative. But even he disappears after 14:72. We have already seen that Mark carefully portrays the women as eyewitnesses of the crucial events from which Peter and the Twelve were absent. But another plausible eyewitness, Simon of Cyrene, appears in 15:21, before readers hear about the women in 15:40.13

Bauckham spends a lot of time discussing the importance of named individuals throughout his book.14 In fact, he points out that when you combine all the names from the four Gospels and Acts, the ten most commonly used names are strikingly similar to the top ten names found on a large database of some three thousand names of known residents of ancient Palestine. By contrast, when you examine the names of characters mentioned in the later Gnostic Gospels (other than the ones already mentioned in the canonical Gospels), they are invariably names that were not in use in first-century Palestine. In other words, they don’t appear to be authentic.

Jens Schröter, a New Testament Scholar at the Humboldt University of Berlin, responded to Bauckham by suggesting that this didn’t necessarily point to the authenticity of Gospel records. Rather, he said, it “simply shows that the Gospel authors gave their narratives a realistic effect.” But in the second edition of Jesus & The Eyewitnesses, Bauckham responded to Schröter by saying,

Even supposing that a Gospel writer would try to make the range of his names realistic…he was only responsible for one Gospel. Nobody planned the…data we get from putting all four Gospels together…While contemporaries would realize that some names were common and others rare, they are unlikely to have known…the relative proportions of name usage…The evidence is therefore much more precise…and strongly suggests that…the names are those of historic individuals.15

The discovery of the “family tomb of Simon of Cyrene” in Jerusalem,16 along with the ossuary belonging to Simon’s son, Alexander, provides further confirmation that the names recorded in the Gospels were not invented by the Evangelists for “realistic effect,” but are indeed the names of authentic eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus.

Note: I discuss another intriguing archaeological discovery in my 30-page exploration of The Identity of the Beloved Disciple. You can read the preview and request the full PDF here.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast and the author of Is Faith Blind? (due in 2024). Shane was one of the creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and has written numerous articles for various sites and publications, including TableTalk, Core Christianity, Modern Reformation, and others.

Related Resources

The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Shane Rosenthal & Richard Bauckham

The Family Tomb of Simon of Cyrene, Tom Powers

Has Simon of Cyrene’s Ossuary Been Found?, James Tabor

Passover & The Last Supper, Shane Rosenthal

Where Was Jesus Crucified?, Shane Rosenthal

Sprinkled Nations & Speechless Kings, Shane Rosenthal

Did Palm Trees Grow in Jerusalem at the Time of Jesus?, Shane Rosenthal

Considering Alternatives to the Resurrection, Shane Rosenthal

Outside the Gospels, What Can We Really Know About Jesus?, Shane Rosenthal

Can We Trust Luke’s Early History of the Jesus’ Movement?, Shane Rosenthal

Scribes of the New Covenant, Shane Rosenthal

Finding Christ in All of Scripture (PDF), Shane Rosenthal

Who is Sergius Paulus?, Shane Rosenthal

Water into Wine?, Shane Rosenthal

It’s interesting to note that the word used by Matthew and Mark when the guards “compelled” Simon is angareuo (ἀγγαρεύω), which is the same word Jesus uses in Mt 5:41 when he said, “If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles.” We know from external sources that soldiers of the period had the authority to conscript others into forced labor at a moment’s notice. For example, one edict from 49 AD indicates that soldiers were forced to stop making requisitions without written authorization, presumably because some had abused their power (see Ceslas Spicq, Theological Lexicon of the New Testament Vo1. 1, p. 24). This not only corroborates the story of Simon’s conscription but it also provides helpful background information that can assist us in our interpretation of Mt 5:41.

Josephus, Apion 2:44

Josephus, Ant. 14:115

Richard Bauckham writes, “The reference to Alexander and Rufus certainly does presuppose that Mark expected many of his readers to know them, in person or by reputation, as almost all commentators have agreed…” (Jesus & The Eyewitnesses, Second Edition, 2017, p. 52). Along these lines, Leon Morris observes that “Alexander and Rufus [were] evidently people known in the church of his day, and probably Christians…would the Evangelists bother naming people like this unless they were Christians?” (Pillar New Testament Commentary: The Gospel of Matthew, 1992, p. 714). See also Larry Hurtado on this point (New International Biblical Commentary: Mark, 1983, p. 265).

Jack Finegan, The Archeology of the New Testament (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 362-363.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.1.1. Eusebius adds, that “Peter’s hearers…were not satisfied with hearing once only…[so they entreated] Mark, a follower of Peter…that he would leave them a written monument” (Ecclesiastical History, 2.15.1).

Richard Bauckham, Jesus & The Eyewitnesses, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI, Eerdmans, 2017), p. 521. Earlier in the book he says “The reference to Alexander and Rufus certainly does presuppose that Mark expected many of his readers to know them, in person or by reputation, as almost all commentators have agreed…” (p. 52).

Finegan, p. 362.

https://jamestabor.com/has-simon-of-cyrenes-ossuary-been-found-and-largely-forgotten/

Finegan, p. 362.

Tom Powers, “Treasures in the Storeroom: Family Tomb of Simon of Cyrene”, Biblical Archaeology Review, July/Aug 2003 (Vol 29, Number 4).

Bauckham, p. 51-52. In his commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, R.T. France seems to agree with this approach: “The preservation of Simon’s name and country of origin suggests that he may subsequently have been involved with the Christian community…[and] the reader might especially notice the need for a new Simon to take the place of the Simon who had so loudly protested his loyalty…” (New International Commentary on the New Testament: The Gospel of Matthew, 2007, p. 1065).

I discuss this on Episode #48, which features an interview with Richard Bauckham.

Bauckham, p. 543-544.

See the BAR article referenced above by Tom Powers.