Deciphering the Clues of Revelation

WARNING! Tugging at these threads may cause you to question everything you think you know about the Bible's final book.

This is Part 1 of a 5-part series. Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Mortimer Adler once noted that of all the “great books,” the Bible is the most difficult to interpret and understand.1 This is partly why there are so many different views about its contents. If this can be said of the Bible in general, it certainly applies to the book of Revelation with all its mysterious symbols and bizarre images. So how are we to make sense of it? Given that there are so many different interpretations of John’s apocalyptic vision, how are we to even know whether or not our views are close to the mark or way off track?

I’m convinced that we’ll have a better chance of unlocking the symbols of Revelation if we come to the book with 1) a “better than average” understanding of the Old Testament, 2) a solid grasp of the Gospels and New Testament Epistles, and 3) if we attempt to interpret the words (and grammar) of a given passage in the light of their original first-century context.

One way to demonstrate the value of the tools I’ve just highlighted is to show how effective they can be in illuminating the meaning of John’s text. One place I like to begin relates to the identification of a mysterious woman who appears in several chapters throughout John’s Apocalypse. I’m convinced that once we begin to understand who and what this character represents, the more John’s imagery and symbolic language will start to make sense.

So let’s jump right in, starting with Revelation 17:3-5:

I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that was full of blasphemous names, and it had seven heads and ten horns. The woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet, and adorned with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a golden cup full of abominations and the impurities of her sexual immorality. And on her forehead was written a name of mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of prostitutes and of earth’s abominations.”

Identifying the Woman & The Seven-Headed Beast

Most commentators agree that the beast is a symbolic depiction of the Roman Empire, since John specifically tells us that the seven heads represent “seven hills” (17:9) and “seven kings” (17:10). But who is the woman and what does she represent? Here, interpreters are divided. Those who see John’s vision as a symbolic representation of timeless truths have tended to view Babylon the Great as a personification of the fallen city of man. Others, who interpret the book as a vivid depiction of future events related exclusively to the end of the world, have argued that the woman likely represents apostate forms of Christianity. At the time of the Reformation, many Protestant interpreters equated Harlot Babylon with the Roman Papacy. In the end, there are so many different interpretations of this particular character that it would be difficult to list them all.

Writing sometime around 64 AD, the apostle Peter concluded his first epistle by saying, “She who is at Babylon…sends you greetings.” Since the city of Rome is here referred to as “Babylon,” many commentators have argued that this is a good way of understanding John’s meaning. But if this is the case, how are we to interpret Rev 18:21, which says: “Babylon, the great city shall be thrown down with violence, and will be found no more.”

As I discussed on episode 66, Isaiah and Jeremiah foretold the fall of ancient Babylon, and their words were fulfilled literally. The city became “a heap of ruins [and] haunt of jackals,” just as they predicted (cf. Is 13:19-22, Jer 51:37). The city of Rome, by contrast, was never made desolate, but is still a vibrant metropolis to this day. So, what accounts for the difference?

Every City & No City

Some have tried to resolve this by suggesting that, though Babylon does refer to Rome, John was merely using the ancient city as a symbol, or an archetype. In this view, therefore, Babylon’s desolation becomes a kind of poetic description of the eventual fall, not of Rome specifically, but of all human civilization. In his commentary on Revelation, Leon Morris advocated this perspective when he wrote that Rome is “a striking embodiment of what John means by Babylon.” In reality, however, “the great city is every city and no city. It is civilized man, mankind organized apart from God. It has its embodiment in every age.”2

Though I used to hold this perspective, I’m no longer convinced that it works. For starters, since ancient Babylon was literally desolated in fulfillment of specific oracles against her (cf. Is 13:19-20, Jer 51:24-26), wouldn’t John’s original Jewish audience have been likely to interpret the words of his prophecy in a similar literal way? This is particularly relevant in light of Rev 18:4, which says: “Come out of her…lest you take part in her sins [and] share in her plagues.” These words very clearly allude to the dire warnings of Isaiah and Jeremiah before the immanent destruction of ancient Babylon (Is 48:20, Jer 50:8), which leads me again to wonder whether the first readers of Revelation would have even thought to interpret the words of his prophecy as a poetic description of the eventual fall of every city in general, and no city in particular.

Here’s another important question. If Babylon the Great does represent the city of man across all times and places, how should the call to “come out of her” be interpreted? Is it a plea for believers to leave the world behind and to live exclusively with other Christians? This is precisely how this passage was interpreted by various Anabaptist sects. In fact, if you’ve ever wondered why the Amish live in their own separate communities, it’s due in part to a misunderstanding of Rev 18:4.3

Perhaps one could see the fall of Babylon as depicting, not the desolation of the city of Rome, but the collapse of the Roman Empire. If so, this would be a different kind of failure, since John makes clear at the outset and in many places throughout his book that his prophecy relates to things that “must soon take place” (Rev 22:6; cf Rev 1:1-3, 2:16, 3:11, 11:14, 22:7, 12, 20). Since Revelation was written in the first century, and the Roman Empire didn’t officially collapse until some time in the fifth century, this doesn’t appear to be a good fit.

Harlot Babylon & Queen Jezebel

If we compare the language of Revelation to images, ideas, and motifs found in the Old Testament, we quickly discover a wealth of material that helps us to make sense of John’s vision. For example, in his book, The Climax of Prophecy, Richard Bauckham points out that when Bible readers are reminded of the story of “Jezebel’s harlotries and sorceries, and her slaughter of the prophets of the Lord, we can see that the harlot of Babylon is also in part modeled on Jezebel.” If it’s been a while since you studied this portion of the Old Testament, here are some of the similarities:

Both Jezebel and Harlot Babylon are presented as wicked and seductive queens (1 Kgs 16:29-30, 21:25; Rev 2:20, 18:7).

While there is a strong emphasis on their external beauty (2 Kgs 9:30; Rev 17:4), both queens practice “whorings and sorceries” (2 Kgs 9:22; Rev 17:1, 18:23).

Both Jezebel and Babylon have murdered saints and prophets (1 Kgs 18:4, 13; Rev 17:6, 18:24), which God promises to avenge (2 Kgs 9:7; Rev 18:24, 19:2).

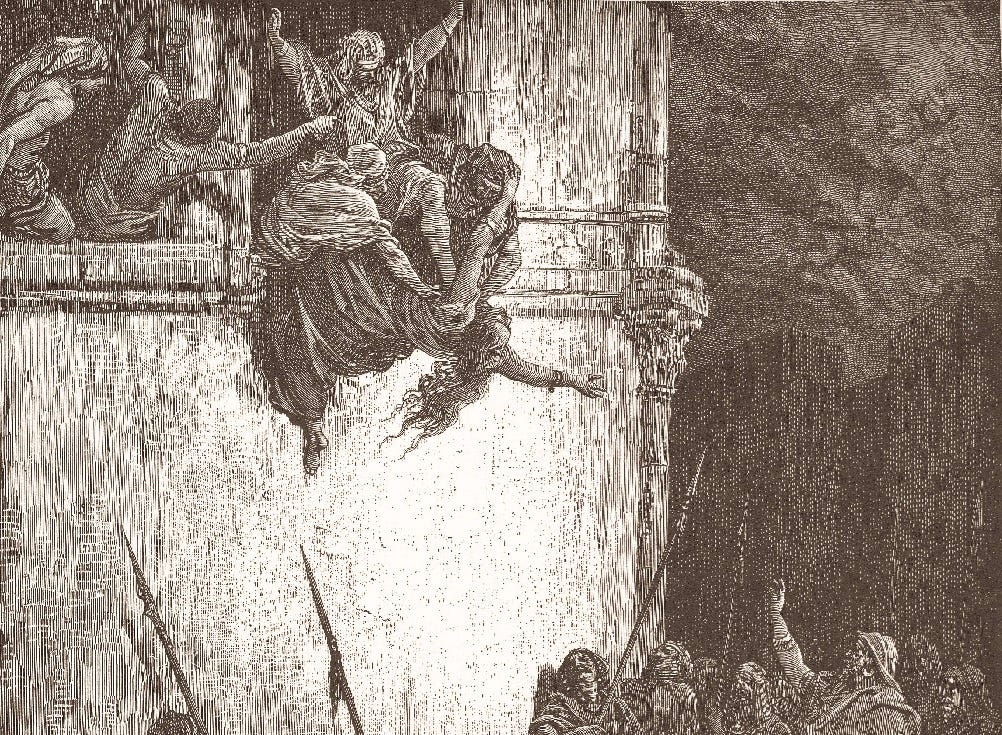

Jezebel’s body was “thrown down…and trampled” (2 Kgs 9:33), just as Harlot Babylon will be “thrown down with violence” (Rev 18:21). In 2 Kgs 9:35-37, Jezebel’s body was eaten by wild dogs, and in Rev 17:16 the harlot is devoured by the beast.

In his book, The Theology of The Book of Revelation, Bauckham wisely observes that:

Revelation is saturated with verbal allusions to the Old Testament. These are not incidental but essential to the way meaning is conveyed. Without noticing some of the key allusions, little if anything of the meaning of the images will be understood. But like the literary patterning, John’s very precise and subtle use of Old Testament allusions creates a reservoir of meaning which can be progressively tapped. The Old Testament allusions frequently presuppose their Old Testament context and a range of connexions between Old Testament texts which are not made explicit but lie beneath the surface of the text of Revelation. If we wonder what the average Christian in the churches of Asia could make of this, we should remember that the strongly Jewish character of most of these churches made the Old Testament much more familiar than it is even to well educated modern Christians.4

After studying the book of Revelation closely for many years, I completely agree with Bauckham’s assessment. Every page is saturated with images, themes, and allusions to the Hebrew Scriptures, which of course means that if we’re to understand this book, we need a “better than average” grasp of the Old Testament. Though Bauckham recognizes the clear parallels between Jezebel and Harlot Babylon, he nevertheless concludes with most contemporary scholars that the latter is a symbolic representation of the city of Rome. In my opinion, however, the fact that Babylon has so many shared characteristics with Jezebel suggests that we should see her instead as a personification of Israel’s apostate leadership, particularly since Jezebel served as Israel’s queen.

There also happen to be a striking number of parallels between the characteristics of Harlot Babylon and Isaiah’s rebuke of the “daughter of Zion” as found in his opening chapter:

Is 1:7 “Your country lies desolate; your cities are burned with fire; in your very presence foreigners devour your land; it is desolate [and] overthrown (compare with Rev 17:16 in which the beast makes the harlot desolate).

Is 1:10 “Hear the word of the LORD, you rulers of Sodom! (compare with Rev 11:8 in which “the great city” is “symbolically called Sodom,” and refers to the place “where their Lord was crucified.”

Is 1:13-15 Her offerings are “an abomination” because her “hands are full of blood” (compare with Rev 17:4 in which the harlot holds a “cup full of abominations” and is “drunk with the blood of the saints”).

Is 1:21-24 “‘How the faithful city has become a whore, she who was full of justice! Righteousness lodged in her, but now murderers…’ Therefore the Lord declares…‘I will avenge myself on my foes…’” (compare with Rev 19:2 in which we’re told that God “has judged the great prostitute…and has avenged on her the blood of his servants”).

Again, these parallels appear to be relatively clear and straightforward. But as in the case of Jezebel, the parallels to the opening chapter of Isaiah provide us with a “reservoir of meaning” that ends up linking Harlot Babylon with Israel’s apostate leadership. There are numerous other striking parallels and verbal allusions scattered throughout the rest of Isaiah’s prophecy, as well as to the writings of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, etc.5 There are also some fascinating parallels found in the book of Lamentations, which, once again, point us in the direction of Jerusalem’s destruction, rather than to the end of human civilization.

The Garment of the High Priest

In one section of his history, Josephus provides us with a vivid description of the high priest’s sacred garment: “[T]he priests stood clothed with fine linen, and the high priest in purple and scarlet clothing, with his mitre on his head having the golden plate on which the name of God was engraved” (Ant. 11:331). What’s fascinating is that his description of the high priest’s vestment seems to mirror not only what we find outlined for the sons of Aaron in the book of Exodus, but also what Harlot Babylon herself appears to be wearing. According to Rev 17:4-5, the woman was “arrayed in purple and scarlet, and adorned with gold and jewels. And on her forehead was written a name of mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of prostitutes and of earth’s abominations.’”

The fact that the woman is “arrayed in purple and scarlet” by itself is noteworthy, but when this is combined with the fact that she has something written on her forehead provides a remarkably close parallel to Israel’s high priest. According to Ex 28:36-38, Aaron was to wear a gold plate above his forehead with the words, “Holy to the Lord” engraved upon it. The words on the harlot’s inscription, however, indicate that she is filled with abominations rather than holiness, and identifies her as the “mother of prostitutes.” In other words, she’s not merely a “whore,” as with Isaiah’s stern rebuke (Is 1:21), but Harlot Babylon appears to be the matriarch of an entire brothel.6

Parallels in the New Testament Gospels

In Rev 18, John tells us that in Babylon “was found the blood of prophets and of saints, and of all who have been slain on earth” (18:20; 24). Though this of course is hyperbolic language, nevertheless, it’s why the great city was to be “thrown down with violence” (18:21). But this language calls to mind specific statements made by Jesus himself. For example, in Lk 21:6 told his disciples that the Jerusalem Temple would be violently “thrown down,” and in his rebuke of the Jerusalem authorities he said the following:

Therefore the Wisdom of God said, ‘I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute,’ so that the blood of all the prophets, shed from the foundation of the world, may be charged against this generation, from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. Yes, I tell you, it will be required of this generation (Lk 11:46-51; cf Lk 13:33-34)

In Matthew’s version of the Olivet Discourse, Jesus cited the words of Isaiah 13 saying, “Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (Mt 24:29). What’s fascinating about this particular statement is that Jesus is alluding to the words of Isaiah 13:10-13 which were originally part of Isaiah’s oracle against ancient Babylon. In my thinking, this could help to explain why John decided to describe Jerusalem as “Babylon.”

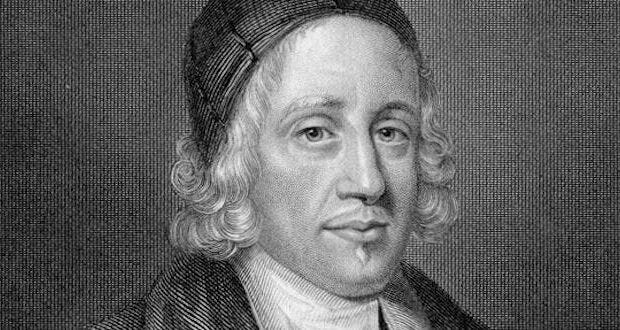

In the Olivet Discourse, Jesus also went on to speak of the “abomination of desolation”7 (Mt 24:15, Mk 13:14), which, according to Luke 21:20, is related to the time that Jerusalem would be surrounded by armies. But this also connects us to Harlot Babylon since she is full of “earth’s abominations,” and will soon be made “desolate” (Rev 17:4-5). In his commentary on this section of Matthew’s Gospel, Cambridge University scholar John Lightfoot (1602-1675), wrote that “Christ’s taking vengeance on that exceeding wicked nation is called Christ’s ‘coming in glory,’ and his ‘coming in the clouds.’” Lightfoot also went on to say:

[W]hen God shall cast off the city and people, grown ripe for destruction, like a carcase thrown out, the Roman soldiers, like eagles, shall straight fly to it with their eagles (ensigns) to tear and devour it. And to this also agrees the answer of Christ, Luke 17:37; when, after the same words that are spoke here in this chapter, it was inquired, “Where, Lord?” he answered, “Wheresoever the body is,” etc., silently hinting…that Jerusalem, and that wicked nation which he described through the whole chapter, would be the carcase, to which the greedy and devouring eagles would fly to prey upon it.8

Lightfoot concluded that “although [apostate Israel] be rejected and cast off…a new church shall be called out of the Gentiles…Hence it appears plain enough that the foregoing verses are not to be understood of the last judgment, but, as we said, of the destruction of Jerusalem.”9

Whether this conclusion is adopted or not, it’s worth pointing out that the first reference to the “marriage supper of the lamb” (Rev 19:9) is juxtaposed with the “great supper of God” a few verses later, where the birds of the air are called to feast on “the flesh of kings [and] mighty men, the flesh of horses and their riders, and the flesh of all men…small and great” (Rev 19:17-18). In my thinking, this fits very closely with Jesus’ description of Jerusalem as a corpse (cf. Mt 24:28, Lk 17:37), and helps to explain why his bride is identified as “the New Jerusalem” (Rev. 21:2).

There is, of course, a great deal more to say here. If you’re new to this way of reading the Revelation, this article has no doubt raised a host of questions. If you’re a paid subscriber, feel free to post your questions in the comments, and I’ll try to address them in the next installment of this article series. In that article, I’ll also discuss the relationship between Babylon the Great and Jesus’ critique of the Judean authorities as expressed in some of his parables.

CLICK HERE to begin reading Part 2 of this article series.

Shane Rosenthal is the founder and host of The Humble Skeptic podcast. He was one of the creators of the White Horse Inn radio broadcast which he also hosted from 2019-2021, and he has written articles for Modern Reformation, TableTalk, Core Christianity, Beautiful Christian Life and other sites and publications.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Articles

Deciphering the Clues of Revelation (Pt 1), (Pt 2), (Pt 3), (Pt 4), (Pt 5), Shane Rosenthal

A Pre-70 Date for Revelation? Shane Rosenthal

A Pre-70 Date for the Gospels & Acts, Views Across the Centuries

The Date of John’s Gospel, Revisited, Shane Rosenthal

The Implications of 70 AD, Shane Rosenthal

New Evidence for a Historical Moses, Shane Rosenthal

The Golden Calf, David Rohl

The Identity of the Beloved Disciple, Shane Rosenthal

Water Into Wine, Shane Rosenthal

Luke’s Key Witness, Shane Rosenthal

Audio

Babylon, Humble Skeptic #66

Decoding the Prophecies of Daniel, Humble Skeptic #68

Jacob’s Ladder, Humble Skeptic #63

Christian Narcissism, Humble Skeptic #67

Did the Exodus Ever Happen? Humble Skeptic #69

Are The Gospels History or Fiction? Humble Skeptic #52

Jewish Views of the Messiah, Humble Skeptic #38

The Intersection of Church & State, Humble Skeptic #53

Books

The Last Days According to Jesus, R.C. Sproul

End Times Bible Prophecy: It’s Not What They Told You, Brian Godawa

Revelation: Four Views, Steve Gregg

The Divorce of Israel, Kenneth Gentry, Jr.

Before Jerusalem Fell, Kenneth Gentry, Jr.

Redating the New Testament, John A.T. Robinson

Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament, Jonathan Bernier

The Antichrist & The Second Coming, Duncan McKenzie

Proof of the Gospel, Eusebius of Caesarea

Son of Man in Early Jewish Literature, Richard Bauckham

A Commentary on the NT from the Talmud, John Lightfoot

The Parousia, James Stuart Russell — FREE

The Early Days of Christianity, F.W. Farrar — FREE

Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren, How to Read a Book (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1940), 294.

Leon Morris, Tyndale Commentary, Volume 20: Revelation, An Introduction & Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1987), 201. Simon Kistemaker similarly writes that “John resorts to using a picture of a woman who represents not only Babylon or Rome but any world city.” This is from his Exposition of the Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2001), 491.

Section 4 of the Schleitheim Confession (1527) says, “We have been united concerning the separation that shall take place from the evil and the wickedness which the devil has planted in the world, simply in this; that we have no fellowship with them…[God] admonishes us therefore to go out from Babylon and from the earthly Egypt, that we may not be partakers in their torment and suffering, which the Lord will bring upon them.”

Richard Bauckham, The Theology of The Book of Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 18.

I’ve listed these parallels in chart form in a PDF resource I’ll be making available soon titled Understanding the Mystery of Babylon The Great.

This is similar to Jesus’ rebuke of the Judean authorities as a “brood of vipers” (Mt 12:34, 23:33-27).

Jesus is referring to Daniel 9:24-27 which spoke of a coming prince who would “destroy the city and the sanctuary…on the wing of abominations shall come one who makes desolate.” This fits with 70 AD, since Titus, son of Vespasian, was in fact prince of the Roman Empire when he destroyed Jerusalem. According to Daniel, all this would take place after an “anointed one [is] cut off” (which Qumran scroll 11Q13 applied to Israel’s coming Messiah).

John Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, Vol 2: Mathew – Mark (Peabody: MA, Hendrickson Publishers, 1989; originally published in 1658), 319.

Ibid., 320.

Great article. Interestingly, the term “carcass” or “corpse” [Strong's 6297. פָּ֫גֶר (peger)] predominantly appears in its plural form within the prophetic texts, with one notable exception where it's used in the singular. This singular form is found in the chapter following Isaiah 13:

“But thou art cast out of thy grave like an abominable branch, and as the raiment of those that are slain, thrust through with a sword, that go down to the stones of the pit; as a carcass trodden under feet.” (Isaiah 14:19, KJV)

In context, this “carcass” refers to Babylon (see Isaiah 14:4).

It’s important to remember that prophecies are deeply rooted in Scripture, and as a prophet, Jesus draws upon the prophetic words that preceded Him. When considering the prophecy Jesus will quote next (Isaiah 13), it’s reasonable to conclude that He is referencing Isaiah 14:19 when He uses the term “carcass.” The Isaiah passage compares Babylon and its king to a corpse that will be destroyed. In this context, Jesus draws a parallel to Jerusalem and its leaders, who, like Babylon, have become spiritually dead. Metaphorically, Jerusalem has become the “city of Babylon.” Just as Babylon fell in Isaiah's day, so too will Jerusalem. Through His words, the meek and lowly Jesus foreshadows a grim fate—rotten flesh will soon be devoured.

Thanks Chad. Unfortunately, there were more than three typos, but they're fixed in the online version. If you read it online (rather than in your inbox), then let me know).